2. Islam as a Source of Inspiration for Science and Knowledge ('Ilm)

2.1. The Rise of Islam and the Early Intellectual Fertilisation

The 7th century witnessed the intellectual and cultural transformation of the Arab people principally as a result of some unique events that occurred in Arabia. The preaching of Islam (da‘wah) by the Prophet Muhammad to his fellow tribesmen, and their reluctant but gradual conversion to the new faith through a process of persuasion and political struggle, influenced the behaviour and outlook of the Arabians, who became imbued with a new sense of purpose. For the first time they were exposed to a set of new ideas on the creation, the Supreme Creator, the purpose of life on Earth and in the Hereafter, the need for a code of ethics in private and public life, the obligation to worship the one and only Lord Almighty of the Universe (Allah), through ritual prayers on a regular basis and sessions of remembrance (dhikr, plural adhkar) or meditation, and to pay homage to a religious and political head as personified by the Prophet Muhammad and, to his Successors or Caliphs (Ar., Khalifah, pl. Khulafa') as leaders of the new community (ummah). All this was new to the Arabs. The whole package of Islamic teachings was propagated by the Prophet and accepted by his fellow Arabs within a generation (610-632 CE).

The Prophet Muhammad taught the peoples of Arabia a great deal. Before the advent of Muhammad, the Arabs had no books and no sacred scriptures. The Qur'an was the first Arabic book and the first scripture in the Arabic language. Its chapters and verse were unique in style and substance in purest Arabic. The Arabs who, from time immemorial, had memorised poems and proverbs, found it easy to learn a part or the whole of the Qur'an for ritual prayer. For the Arabs, the Qur'an, it would seem, was a substitute for old Arabic poetry. The difference was that poetry was recited at home and in the market, whereas the Qur'an was recited only after ablution and reverential devotion. Incidentally, the word“al-Qur'an”

means ‘the recitation' or the reading. It is essentially a book of revelation from God, embodying Islamic law and ethical code.

Through an understanding of the Qur'an, the Arabs began to think and behave differently from their polytheistic ancestors (mushrikun), becoming more like Jews and Christians in their monotheism. Thus they had begun to reflect on the mysteries of the universe and the importance of being imbued with a sense of brotherhood. For the first time their lives were regulated by a book of revelation and were turned around by it. The Qur'an was to Muslims what the Bible was to the Christians and the Torah to the Jews; and they were more affected by the Qur'an than Christians and Jews were by their Scriptures.

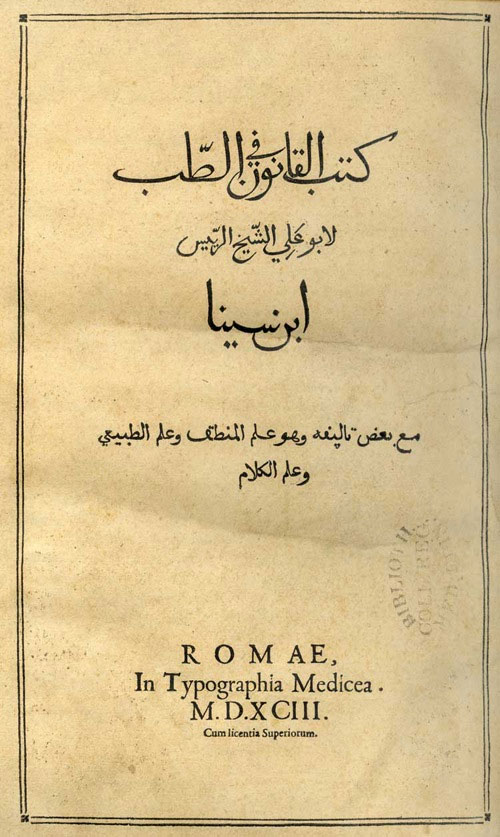

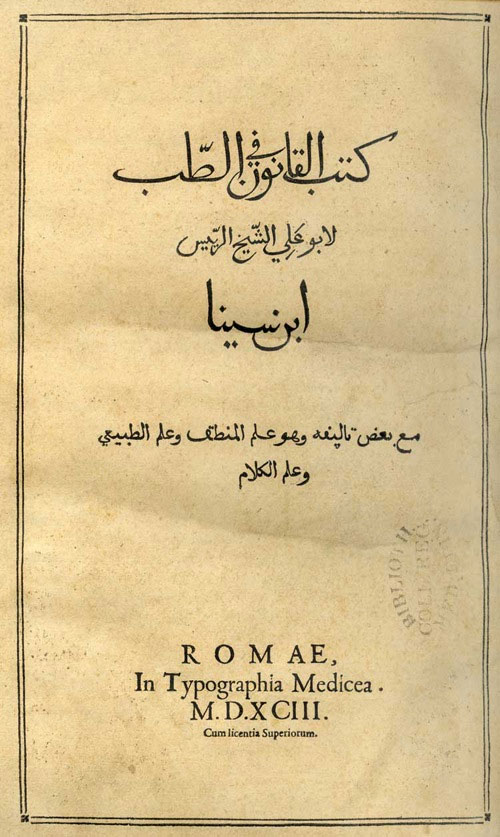

Figure 6:

The title page of Ibn Sina's (11 century CE) Kitab Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb taken from a printed copy of the book, based on a Florentine manuscript, in the rare book collection of the Sibbald Library at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

When the Islamic education was introduced to his disciples by the Prophet through the process of da‘wah (‘call to Islam'), it was as though a whole people went to school to read, write and memorise their first primer, al-Qur'an. Among the celebrated teachers of the Qur'an in early Islam, were ‘Ubadah ibn al-Samit, Mus‘ab ibn ‘Umayr, Mu‘adh ibn Jabal, ‘Amr ibn Hazm

, and Tamim al-Dari. These teachers were sent to various parts of Arabia and beyond. Islamic education begins with the lessons of the Qur'an. It is a religious duty and an obligation for every Muslim to preach and teach to his fellow Muslims and non-Muslim acquaintances what he knows of the Qur'an and the Traditions. Such a process of informal mass education and Islamisation began in the Arabian Peninsula during the Prophet's last years and the process was carried forward under his successors. These early Muslims also became familiar with the life style of the Prophet (Sunnah). Everything the Prophet said, did, approved of, condemned and encouraged others to do became the source of inspiration for Muslims and the Sunnah (custom, or Islamic way of life) for the Muslim community. The Qur'an describes Muhammad as the unlettered/illiterate Prophet (al-Nabi al-Ummi)

, which was true at the time of his receiving the first revelation from God through the angel Gabriel (Jibril) at the age of 40, when he was ordered to ‘Read in the Name of God who creates, creates man from congealed clot; Read and your Lord is most gracious, Who teaches by the pen; (He) teaches what man(kind) does not know'

. To Archangel Gabriel's command, Muhammad replied that he was unable to read, a clear indication of his illiteracy, his knowledge of Jewish and Christian religions being based on what Gabriel communicated to him directly. However, according to an authority on Muhammad, after he received the divine order to ‘read' (Iqra'), ‘he could - and did - learn how to read and write, at least a bit'

. This explains how letters he dictated to his amanuenses were signed by him. Therefore, by the end of his life Muhammad was literate. The collection of Muhammad's words and thoughts and his tacit approval is known as hadith (plural ahadith). This hadith became one of the basic sources of Islam.

2.2. The Islamic Background to Intellectual Activity

The question that now arises is: ‘What is the relevance of the Qur'an and Hadith to Islamic science?' To begin with, everything Islamic is influenced by these two sources. The learning process of the Arabs began with the Qur'an and everything else followed accordingly. The Prophet told his disciples:“Wisdom (Hikmah) is the object for the believers”

. Thus Muhammad created an incentive to pursue all kinds of knowledge, including science and philosophy.

The questions that we should ask and to which we should find answers are: ‘does Islam encourage or stifle knowledge in a broad sense and secular sciences in particular? Is there any conflict between reason (‘aql) and revelation (wahy) in Islam?'

The Arabic term ‘ilm literally means science and knowledge in the broadest sense. It is derived from the Arabic verb ‘alima, to know, to learn. Therefore, ‘ilm implies learning in a general sense. The Prophet Muhammad, like all the Semitic Prophets before him, was an educator and spiritual mentor. He contended that the pursuit of knowledge (‘ilm) is a duty (fardh) for every Muslim

. This statement unmistakably attaches the highest priority to knowledge and encourages Muslims to be educated. Another statement praises religious knowledge even more highly, maintaining that it is a key to various benefits and blessings and that those who teach the Qur'an and Hadith have inherited the role of the ancient Prophets

. In a separate statement, Muhammad said that the scholars of religion (‘ulama') are the trustees of the Messengers (of God) (umana' al-Rusul)

. In praise of knowledge, the Prophet also said that the pursuit of knowledge is superior to ritual prayer (Salah), fasting (during Ramadan), pilgrimage (Hajj) and the struggle for Islam (Jihad) in promoting the cause of God

. This last Tradition is often misinterpreted by some Muslims who think (quite mistakenly) that religious learning and the pursuit of science exempts them from prayer, fasting, pilgrimage and Jihad. This is not at all the intention of the statement. What it emphasizes is that religious education is no less important than the time and efforts devoted to Salah, Sawm, Hajj and Jihad. Thus learning gets priority over those usual duties of a believer.

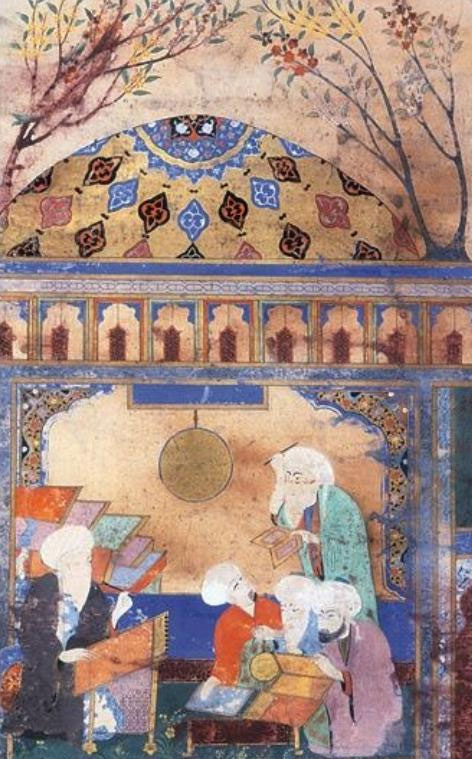

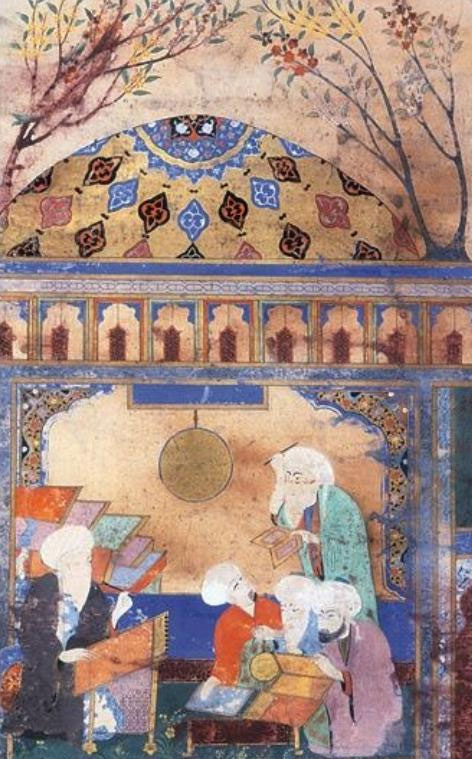

Figure 7:

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi is pictured at his writing desk at the high-tech observatory in Maragha, Persia, which opened in 1259. © British Library.

The concept of science and knowledge was also widely diffused in the Prophet's Traditions and in Arabic belles lettres (adab). It only proves the point that Islam inspires its adherents to think of science or knowledge not only for its spiritual and utilitarian value, but also as an act of worship. Some of the sayings attributed to the Prophet Muhammad elevated the pursuit of knowledge as an act of worship. The discourse on knowledge in Arabic sources frequently use two terms, ‘ilm and ‘aql. The former applies to sacred knowledge as well as profane science, and ‘aql connotes intellect or intelligence.

2.3. Unity of Knowledge: Religious, Rational and Experimental

The first subjects that began to take shape among Muslim scholars after the spread of Islam were related to the commentary on the Qur'an (tafsir), Traditions (Hadith) and Asma' al-Rijal (biographies of Hadith scholars), Sirah (Biography (of the Prophet) and Maghazi (Battles of the Prophet), Usul al-Din (theology), Fiqh (Jurisprudence) and Usul al-Fiqh (methodology/principles of Jurisprudence). The Arabic language was classified by Ibn Khaldun as an auxiliary science to explain the terminology of the Qur'an

. It would therefore appear that during the 1st and 2nd Hijri centuries a number of new subjects were gradually developed to explain the Qur'an, the Traditions and Islamic history. On the whole the study of basic religious sciences was given priority over other subjects.

The Islamic scholar Muhammad ibn Idris al-Shafi'i (d. 204/820) classified science into two broad categories, science of the bodies (‘ilm al-abdan) and science of the religions (‘ilm al-adyan)

. In the hierarchy of science Islamic scholars placed religious subjects at the top of their list, although secular sciences, such as mathematics, physics, chemistry, astronomy and philosophy were recognised as useful branches of knowledge. From the ‘Abbasid period onwards, Muslims were avid readers of religion, science and philosophy. In fact, religious and philosophical sciences developed in parallel. Although some religious scholars (the ‘ulama' and fuqaha') undervalued philosophical sciences

, such secular subjects were, however, widely tolerated, allowed to flourish in Islamic society and were accommodated in the educational curriculum. The critical attitude of the ‘ulama' towards the philosophical sciences has belatedly attracted severe criticism from some Orientalists

. More often than not, it seems quite clear that there was no clear division between sacred and profane sciences. Usually, scholars of the calibre of Ibn Khaldun divided science into two classes, namely the traditional sciences (‘ulum naqliyah) and the philosophical sciences (‘ulum 'aqliyah)

.

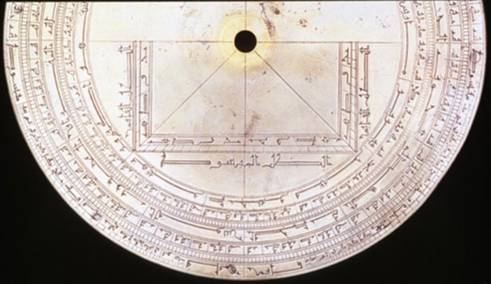

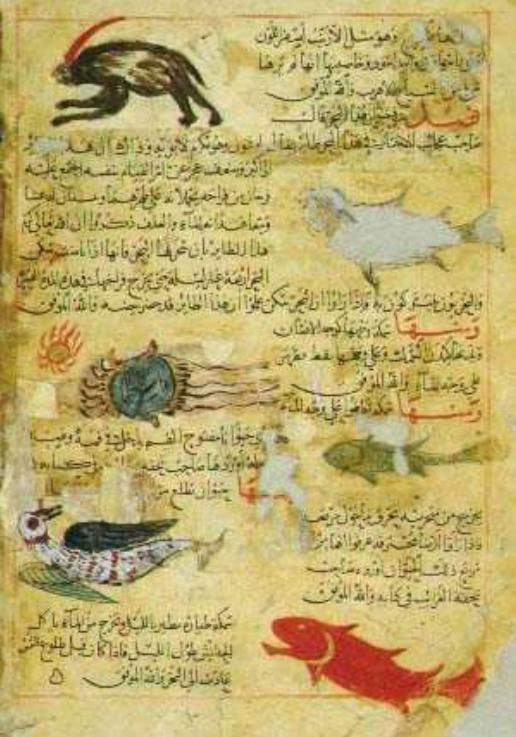

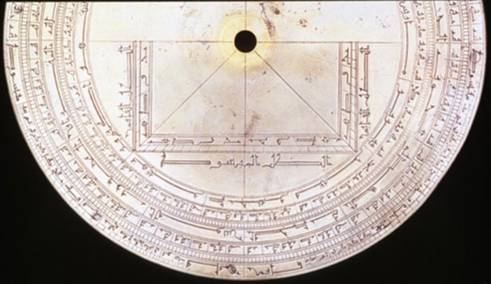

Figure 8a-b:

The front and back of an Islamic Astrolabe in the Whipple Museum, Cambridge. This astrolabe is signed“Husain b. Ali”

and dated 1309/10 AD. It is probably North African in origin, and is made of brass. It has four plates (for the front of the astrolabe, representing the projection of the celestial sphere and marked with lines for calculation), each for a specific latitude, and 21 stars marked on the rete (the star map, with pointers, fitting over the plate).

Many outstanding scholars emphasized the unity of knowledge. Thus scientists of the calibre of Jabir ibn Hayyan, al-Kindi, al-Khwarizmi, al-Razi, al-Biruni, al-Farabi and Ibn Sina were as adept in the religious (sacred) sciences as in the profane sciences of medicine, philosophy, astronomy or mathematics. They were conscious of the various dimensions of science.

The Prophet Muhammad was credited with a number of statements regarding cleanliness, health and medicine. These were collected together and became known to Muslims as the Prophetic medicine (al-tibb al-nabawi). A number of books bear this title, including one written by Ibn al-Qayyim al-Jawziyyah

and another by al-Suyuti

. These books contain some authentic statements of the Prophet and include herbal medicine and natural cures. Drinking honey and reciting the Qur'an are recommended as a panacea for all kinds of ailments. One such Tradition asserts that every disease has a cure

. In other words, God has provided cures for all kinds of disease. Commenting on this and other Traditions, Muhammad Asad says that when his followers read the Prophet's saying (quoted in al-Bukhyii):“God sends down no disease without sending down a cure for it as well”

. They understood from this statement that by searching for cures they would contribute to the fulfilment of God's will. So medical research became invested with the holiness of a religious duty

Ibn Khaldun, while commenting on the Prophetic medicine, said that it resembled medicine of the nomadic type, which is not part of the divine revelation, and therefore is not the duty of Muslims to practise it

.

It is generally believed by Muslims that no contradiction exists between religion and science. However, this is not the case in Europe, as we shall see.

2.4. Maurice Bucaille's Theses

The relevance of science to scripture has been examined by a French scholar, Maurice Bucaille, whose study The Bible, the Qur'an and Science (an English version of his La Bible, le Coran et la science)

is relevant to our discussion. Bucaille, aware of the fact that Judaism, Christianity and Islam are Abrahamic religions, makes the following observations.

1. The Old Testament, the New Testament and the Qur'an differ from each other. The Old Testament, he claims, was composed by different authors over a period of nine hundred years. The Gospels, on the other hand, were the work of different authors, none of whom witnessed in person the life of Jesus. The latter merely relayed what happened to Jesus. Islam has something comparable to the Gospels in Hadith, which are collection of sayings and descriptions of the Prophet. Comparing the Gospels with the Hadith Bucaille says:“Some of the Collections of Hadiths were written decades after the death of Muhammad, just as the Gospels were written decades after Jesus. In both cases, they bear human witnesses to events in the past”

.

Some Western scholars, including Ignaz Goldziher and Joseph Schacht, have argued against the authenticity of certain Traditions. Even Bucaille wrote critically

of a few that dealt with the ‘creation myth' finding them incompatible with modern science. Such reservations inevitably offend Muslims, because the Traditions enshrine the moral and spiritual values of Islam. However, the author is equally critical of the four Canonic Gospels and cannot therefore be accused of bias or prejudice. In fairness to Bucaille, it should be said that he was studying the Scriptures from the point of view of science and not vice versa. His objectivity, though inevitably hurtful to some, is rare even in modern scholarship. The author boldly argues that Christianity does not have ‘a text that is both revealed and written down. Islam, however, has the Qur'an, which fits this description'

.

The Qur'an is an expression of the Revelation from God delivered by the Archangel Gabriel to Muhammad, which was memorised, written down by the Prophet's amanuences

and recited as liturgy. The Qur'an was thus fully authenticated. The Revelation lasted around twenty years. Muhammad himself arranged the chapters and the full text was compiled into a book by Caliph ‘Uthman ibn ‘Affan about eighteen years after the death of the Prophet(ca 650 CE).

2. Debates between the Biblical Exegists and Western scientists have arisen as a result of discrepancies between the Scriptures and science

. In contrast, many verses of a scientific nature can be found in the Qur'an. Bucaille asks:“Why should we be surprised at this when we know that, for Islam, religion and science have always been considered the twin sisters? From the very beginning Islam directed people to cultivate science; the application of this precept brought with it the prodigious strides in science taken during the great era of Islamic civilization, from which, before the Renaissance, the West itself benefited ”

.

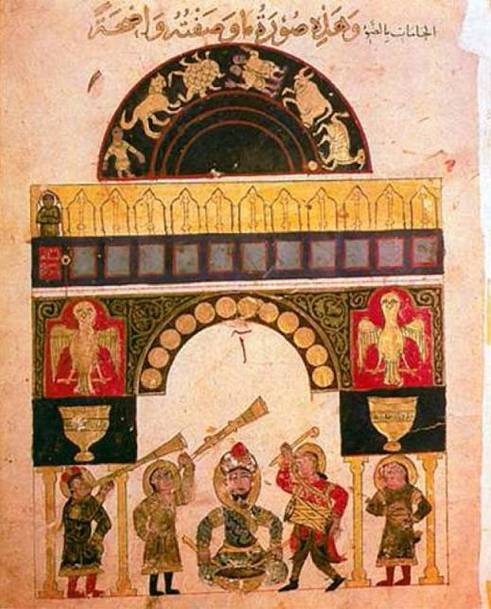

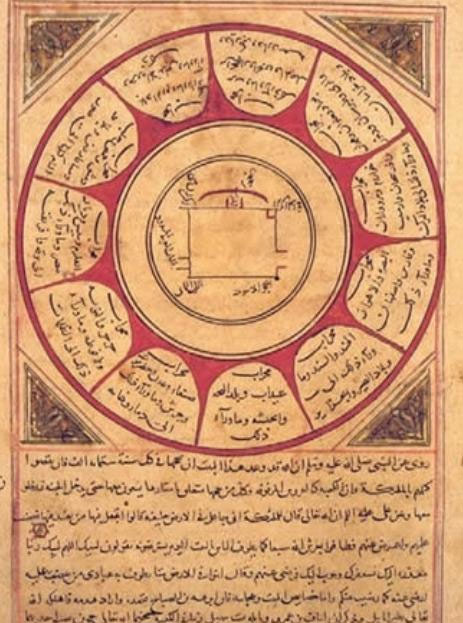

Figure 9:

The calendar scales (round the outside edge) on an Islamic astrolabe in the Whipple Collection, Cambridge, a case of calendrical applications of Islamic astrolabes. Islamic astrolabes have calendar scales on them that enable the positions of the moon and the dates of the lunar calendar to be calculated easily.

According to Bucaille, some verses of the Qur'an have puzzled interpreters until the discoveries of modern science attested to the truth. The range of the scientific data contained in the Qur'an is explored in the following pages.

The creation of the heaven and earth and everything in them happened in six days

. The term six“days”

is interpreted by modern exegetes of the Qur'an as six“periods”

or“stages”

. The Qur'an also refers to a day as being equivalent to a thousand earthly years

. In another context, a day is described as being equivalent to 50,000 years

.

Moreover, some verses of the Qur'an refer to such things as ‘heaven and the earth being a solid mass

, which was ripped apart. There are references to navigation in the seas

; and God created meat (fish)

for food, and precious objects, such as coral

(marjan) and pearls

for use as jewellery; that God created an orderly cosmos in which every planet, including the sun and the moon, moved along its prescribed orbit

. For instance, the sun does not overtake the moon

; and that God created male and female for humans

as well as for vegetables and animal kingdoms

; that man was created through the sex

act and that women's menstruation

is a time for sexual abstinence; that God created everything out of water

. God sends down rain

to revive the dead earth to produce and for growing grains, fruit and vegetable; and that He let the earth produce all kinds of food

; that God created cattle to produce milk for humans

; that He created horses, mules and donkeys as working animals

; that He created the constellation

, and the sequence of day and night

as natural phenomena to remind people of God's majesty and power and to encourage them to study astronomy. There are many more examples, but these should suffice for our purpose.

Nowhere in the Qur'an is there anything which has been proven scientifically untrue? Thus Maurice Bucaille, after considering all the scientific data in the Qur'an concluded as follows:“In view of the level of knowledge in Muhammad's day, it is inconceivable that many of the statements in the Qur'an which are connected with science could have been the work of a man. It is, moreover, perfectly legitimate, not only to regard the Qur'an as the expression of a Revelation, but also to award it a very special place, on account of the guarantee of authenticity it provides and the presence in it of scientific statements which, when studied today, appear as a challenge to explanation in human terms”

.

Imbued with the values of the Qur'an, the early Muslims were psychologically ready to travel widely in search of all kinds of knowledge and were urged to study nature. Through trying to establish the coordinates of longitude and latitude of the Ka‘bah, the Muslims developed their knowledge of geography and cartography. Books were written and maps were used as illustrations. As a result of the study of science in other cultures through the translation of books in Greek, Sanskrit and Middle Persian at the institutions like the Bayt al-Hikmah in Baghdad from the 9th to the 11th century CE, the incipient scientific movement among the Muslims received a boost and contributed to the further development of science in the lands of the Caliphate.

0%

0%

Author: Muhammad Abdul Jabbar Beg

Author: Muhammad Abdul Jabbar Beg