9. Medicine

Our knowledge of the history of Islamic medicine in the ancient and medieval Middle East is mainly based on biographical sources, such as Ta'rikh al-Hukama (History of the Physicians and Philosophers) by Ibn al-Qifti and ‘Uyun al-Anba' fi Tabaqat al-Atibba' (Sources of Information on the Classes of Physicians) by Ibn abi Usaybi'ah, besides some fragmentary references in literary works.

In pre-Islamic Arabia medicine consisted of herbal and natural remedies. The Prophet Muhammad's statements regarding cleanliness, diet, sickness and cure were collected together in books, which came to be known as Tibb al-Nabawi (or the Prophetic medicine) but little is known about how this medicine was practiced. The Shi‘ite Muslims added to the medical canon with Tibb al-A'immah or medicine of the Imams (Leaders).

There is also some indication of foreign medical influence reaching Arabia from neighbouring lands, such as Persia, where the Arabian physician al-Harith ibn Kaladah al-Thaqafi

studied medicine in Jundishapur, the ancient seat of a hospital and medical college. Persian, Indian and Nestorian physicians were said to have practised at the Jundishapur hospital and to have translated various medical books from Indian and Syriac texts into Pahlavi. However, recent research

has questioned whether a hospital and medical school ever existed at Jundishapur in Ahwaz. Instead, it is claimed that Jundishapur had only an infirmary, and no medical school. What interests us here, however, is that al-Harith ibn Kaladah al-Thaqafi studied medicine in Jundishapur. Significantly, Ibn Kaladah was a contemporary of the Prophet Muhammad, and though his existence has recently been doubted, he was a real person. It is known that he originated in Ta'if and belonged to the tribe of Thaqif. His link with the Jundishapur centre suggests a Persian influence in the advancement of the early Arabian medicine. Harith was reported to have met the Prophet during the Farewell Pilgrimage, to have cured a sick Sa‘d ibn Abi Waqqas. Harith's conversion to Islam, however, has been questioned. From the little we know of his medical theories, it is possible to conclude that his“main point was the Arab view that excess of diet was the main cause of all disease. He also recommended the simplest possible way of life. Diet should be of the plainest. Water is to be preferred to wine and salt and dried meat to fresh meat. The dietary should include fruit. The hot bath should be taken before meals”

.

There is also evidence to suggest that a physician, Ibn Abi Rimthah, used surgery to remove a mole from the Prophet's back

. For this, according to al-Qifti, Ibn Abi Rimthah was given the title of ‘Tabibu-Allah' (literally God's physician), whereas al-Harith b. Kaladah was known as the ‘physician of the Arabs' (Tabib al-'Arab), just as al-Kindi was called the philosopher of the Arabs (Faylasuf al- ‘Arab).

Figure 18:

Diagram of the eye from Risner's edition of Opticae thesaurus. Alhazeni Arabis libri septem Opticae thesaurus... (Basilea, 1572), the first edition of the Latin translation of Ibn al-Haytham's Kitab al-manazir, the most important and most influential Arabic treatise on physics, that exercised profound influence on Western science in the 16th and 17th centuries. Sarton calls Ibn al-Haytham“the greatest Muslim physicist and one of the greatest students of optics of all times.”

During the Umayyad period (660-750 CE), parts of North Africa, Spain, eastern and northern Persia, and the Indian province of Sind were being conquered. Such conquest started a process of gradual integration of the Arabs with non-Arabs, between Muslims with non-Muslims, and allowed the intrusion of non-Muslim ideas (including Greek, Persian and Indian secular traditions) into the formation of literature and science. It was at Jundishapur that ancient Indian writings on toxicology were translated from Sanskrit into Arabic (e.g. Kitab al-Sumum, according to Hajji Khalifah). Elsewhere, it has been claimed that knowledge of Indian drugs, including poisons, spread from Jundishapur to the Middle East. ‘Ali b. Sahl Rabban al-Tabari (d. ca 240/854-5CE), in the first systematic medical work in Arabic, Firdaws al-Hikmah (The Paradise of Wisdom), expounded upon the Arab knowledge of Indian medicine, and Syriac and Greek medical literature during the 9th century CE. Elsewhere, the belletrist al-Jahiz (d.255/869) also acknowledged the advances made by Indians in the sciences of astronomy, mathematics and medicine and pharmacology

. Modern research has also discovered that contact existed between the Arabs and the Chinese, and that Chinese medical herbs were used in West Asia. It has been suggested that the Arab polymath al-Kindi indicated in his pharmacopeia that Arab physicians were already using Chinese herbs during the 9th century CE. A century later, Ibn Sina recorded that seventeen medical herbs imported from China were currently in use and that even the Chinese pulse theory was applied by some physicians. Chinese medical influence reached a peak in Persia and the rest of the Middle East during the era of the Ilkhanids (1256-1335), when Rashid al-Din Fadlullah, the wazir of Ghazan Khan (1295-1304 CE) had some Chinese medical books translated into Persian, including Tansuk-Nama

.

Among the earliest notable translations into Arabic during the Umayyad period were the Kunnash (Pandects) of Ahron al-Qass, a Priest of pre-Islamic Alexandria. The translator was a Basran-born Jewish Physician, Masarjis or Masarjawaih

who lived, according to Ibn al-Qifti, during the reign of ‘Umar II (d. 101 AH/720 CE) and who was credited with writing medical treatises, including Kitab Qawi al-At'imah (a treatise on food) and Kitab Qawi al-Maqaqir (a book on drugs). A book on the Substitution of Remedies (Kitab fi Abdal al-Adwiyah) was also attributed to Masarjawaih, but modern commentators, such as Max Meyerhof, have rejected the claim. Little is known of Masarjawaih's medical practice, but we know that he prescribed eating raw cucumber on an empty stomach for a patient who complained of constipation.

In Damascus, during the Umayyad era, some events of medical significance included the amputation of a leg infected with gangrene. In this rare case the leg belonged to a celebrated Arab, namely ‘Urwah ibn al-Zubayr, a brother of ‘AbdAllah ibn al-Zubayr ibn al- ‘Awwam. While visiting (ca 85 AH/785 CE) the Umayyad prince al-Walid, he became afflicted with gangrene (al-ikla)

in his foot. ‘Urwah lived for another eight years, after the leg was amputated in the presence of al-Walid b. ‘Abd al-Malik, the future Umayyad Caliph (r.86-96/705-15 CE) and died in Madinah in 94 AH/713 CE. This celebrated amputation was also recorded by Abu 'l-Faraj al-Isfahani in his entertaining literature Kitab al-Aghani, and Ibn al-Jawzi in his Dhamm al-Hawa'.

It is clear from our sources that Islamic science and medicine developed rapidly in Baghdad under the early ‘Abbasid Caliphs, especially al-Mansur, Harun al-Rashid and al-Ma'mun. Among the prominent medical personalities of this period were members of the Bukhtishu‘ family who moved from Jundishapur and established a prosperous medical practice in Baghdad. The translation into Arabic by the physician Hunayn ibn Ishaq and his son, Ishaq b. Hunayn, and others, of medical treatises, mainly from Greek, brought Arabic medicine under the Hellenistic medical influence. In particular, the translations of Hunayn made the works of Hippocrates and Galen available and shaped the Arabic medical vocabulary in classical Arabic. Hunayn's original medical treatises include Kitab al-Masa'il fi'l-Tibb (a book on medical problems) and Kitab al-‘Ashar Maqalat fi 'l-‘Ayn (Ten Treatises on the Eye), both of which became standard works during the 9th and 10th century. The first was used by the Hisbah officers (municipal officials) to assess the professional qualifications of physicians. Hunayn also edited the translation of Istafan bin Basil of the Materia Medica of Pedanius Dioscorides (1st century BCE). This was variously titled as Hayula ‘ilaj al-Tibb, Kitab al-Adwiyah al-Mufrada and Kitab al-Hasha'ish, during the 3rd century AH/9th century CE. This translation provoked a number of commentaries and these served as the most valuable works of Arabic pharmacology. Al-Biruni's Kitab al-Saydalah (The Book of Drugs), which records 850 drugs, survives in a modern edition. The most notable Arabic book of this genre is Kitab al-Mughni fi'l-Adwiyat al-Mufradah (a treatise on simple drugs) by the 13th century Andalusian Ibn al-Baytar. This records 1400 drugs of mineral, vegetable and animal origin.

The publication of medical works by Muhammad ibn Zakariyya' al-Razi (Latinised Rhazes) (d. 313 AH/925 CE), Ali b. ‘Abbas al-Majusi, the Andalusian surgeon Abu 'l-Qasim al-Zahrawi, the ophthalmologist ‘Ali ibn ‘Isa, and Abu ‘Ali Ibn Sina, hailed by his contemporaries as the prince of the physicians (Ra'is al-atibba'), marked a high point in Islamic medicine.

Between the 9th and 14th centuries, Islamic medicine and pharmacology advanced to such a point that some medical works which were translated into Latin in Toledo and southern Italy influenced the development of medicine in medieval Europe. The achievements of this Golden Age are worth noting.

Al-Razi, the great medical systematiser of all Muslim medical authorities, derived his surname from his native city Rayy, where he became the chief physician of the hospital, later holding the same position in Baghdad. Al-Razi (d. 313 AH/925 CE), was the greatest clinician and pathologist of his time. His notebooks, which comprised 25 volumes of Kitab al-Hawi fi'l-Tibb (The Comprehensive Book of Medicine), were translated into Latin as the Continens by the Jewish physician Faraj bin Salim or Farraguth in 1279 CE. However, al-Razi's magnu opus, according to some, was not al-Hawi, but Kitab al-Jami' al-Kabir (the Great Medical Compendium). Besides this, a treatise on Smallpox and Measles (Kitab al-Jadari wa'l-Hasbah), which was translated into Latin and other European languages as Liber de Pestilentia, earned him international recognition. Other medical works included Kitab al-Hasa fi 'l-Kula wa-'l-mathana (Stones in the kidney and bladder) and Kitab al-Mansuri (Latin Liber Medicinalis ad al Mansorem), which was dedicated to his patron Mansur ibn Ishaq, the Samanid governor of Rayy. He also wrote a book on psychic therapy, Al-Tibb al-Ruhani (lit. Spiritual Medicine)

, in which he provided insights into the theory and practice of clinical and psychiatric medicine. Like Galen, he believed that a physician should also be a philosopher, but his independence was articulated in his Shukuk 'ala Jalinus (Doubts about Galen). His“clinical records did not conform to Galen's description of the course of fever. And in some cases he finds that his clinical experience exceeds Galen's”

.

After al-Razi, another influential figure in Islamic medicine was ‘Ali b. ‘Abbas al-Majusi (Latin Haly Abbas) whose famous Complete Book of the Medical Art (Kitab Kamil al-Sina'ah al-Tibbiyah), also known as Kitab al-Maliki (Latin Liber Regius), was written while he was director of the ‘Adhudi Hospital in Baghdad. The work contained important observations on medical theories and diagnoses and was a dominant text throughout the East. A contemporary of Haly Abbas, Abu 'l-Qasim al-Zahrawi (in Latin Abulcasis/Albucasis), who served the Andalusian Caliph Abd al-Rahman III al-Nasir (300-350/912-961) in Cordoba. He wrote Kitab al-Tasrif li-man 'ajiza 'an al-Ta'lif, a medical encyclopaedia, dealing with 325 diseases. The part of this book devoted to surgery described cautery, incisions, bloodletting and bonesetting

. All surgical methods together with the tools were illustrated.

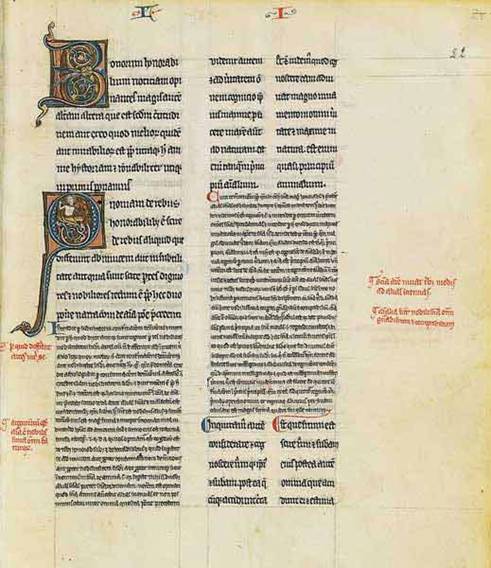

In the history of Islamic medicine, Abu Ali al-Husayn ibn Sina (known in the West as Avicenna) was a towering figure. Born at Afshana near Bukhara in 370 AH /980 CE, he died at Hamadhan in 428/1037CE. Like al-Razi, he was a great physician and philosopher and wrote a dozen medical works, although the historian Ibn al-Qifti listed a few more. Among these were A Book of Healing (Kitab al-Shifa'), in 18 volumes, Kitab al-Qanun fi 'l-Tibb (The Canon of Medicine) in 14 volumes, Kitab al-Adwiyah al-Qalbiyah (Medicine of the Heart)), Kitab al-Qawlanj (Book of Colic) and a mnemonic in verse for physicians, al-‘Urjuzah fi 'l-Tibb. Ibn Sina's full bibliography includes 270 titles. However, his magnum opus was Kitab al-Qanun fi 'l-Tibb or The Canon of Medicine, which was, according to Goichon, ‘the clear and ordered“Summa”

of all the medical knowledge of Ibn Sina's time, augmented from his own observations”

. This Canon (Qanun), through its European translations, became ‘a kind of bible of medieval medicine, replacing to a certain extent the works of al-Razi. It was printed in Rome as early as 1593, shortly after the introduction of Arabic printing in Europe

.'

It is tempting to compare the stature of Al-Razi and Ibn Sina as medical authorities of the pre-modern world. It has been aptly noted that Al-Razi made his original contribution in the practice of medicine, whereas Ibn Sina gained prominence in medical theory. Despite their greatness, both were subjected to harsh criticism by al-Ka‘bi and ‘Abd al-Latif Baghdadi respectively. Islamic medicine declined after the death of Ibn Sina, but many commentaries on and epitomes of the Canon (Qanun) were made by successive generations of physicians. Among the commentaries, the most notable was that of Ibn al-Nafis (d. 687/1288), the chief physician in Cairo, who composed Sharh al-Qanun, a commentary on the entire Canon, and Mujiz al-Qanun and an epitome Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun, which he devoted to comment on its anatomical and physiological aspects, It is in the latter that Ibn al-Nafis described his discovery of the lesser or pulmonary circulation of the blood, which made him famous.

Within a century of his death, Ibn Sina's works began to appear in European translations. Between 1170 and 1187, Gerard of Cremona translated the Canon of medicine at the order of Frederick Barbarossa. Even lesser works of Ibn Sina were translated, including the Sufficientia by Gundisalvus, whilst Armengaud translated Canticum de Medicina (Urjuza fi'l-tibb) with Ibn Rushd's commentary on it; and Arnold of Villanova did the same in De Virivus Cordis. Michael Scot, in collaboration with Andrew the Jew, translated some works of Ibn Sina into Latin between 1175 and 1232 CE. The death in 1285 of Farraguth, the translator of Al-Razis' Continens, brought the era of Latin translations to an end. The Universities of Montpellier and Bologna, taught the works of Al-Razi and Ibn Sina in their medical schools.“From the 12th to the 17th century, Rhazes and Avicenna were held superior even to Hippocrates and Galen”

. Al-Razi is depicted in the stained glass of the chapel in Princeton University, and in the University of Brussels lectures on Ibn Sina were given until 1909.

Al-Razi's book Diseases in Children may justifiably earn him the title of father of paediatrics. Ibn al-Jazzar (d. 984 CE) of Tunisia also wrote on the care for children from birth to adolescence, though this work was later surpassed by the Cordoban ‘Arib ibn Sa‘id, whose treatise on gynecology, embryology and paediatrics was published in Andalusia.

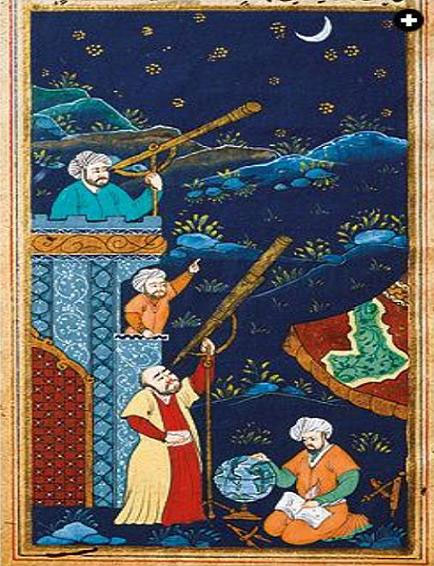

In the dusty conditions of the Middle East, eye diseases were common and Muslim physicians developed special skills for treating blindness. Although most medical books devoted a separate chapter to eye diseases, monographs were also written on the subject. One early work on ophthalmology was Hunayn ibn Ishaq's ‘Ashar Maqalat fi'l-'Ayn (Ten Treatises on the Eye), which remained a standard for many centuries. However, the most important book was ‘Ali ibn ‘Isa's (d. 400/1010 CE) Dhakhirat al-Kahhalin (Treasury for Ophthalmologists), which was translated into Latin as Tractus de Oculis Jesu Ben Hali.

The transfer of scientific knowledge from Arabic into Latin contributed to the European Renaissance.

0%

0%

Author: Muhammad Abdul Jabbar Beg

Author: Muhammad Abdul Jabbar Beg