9: POWER, PURITY AND THE VANGUARD

Educational ideology of the Jama’at-i Islami of India

Irfan Ahmad

In order to keep everything as it is,

we have to change every thing.

Giuseppe di Lampedusa, The Leopard

The argument

The dominantmode of

understanding has it that Islamism or the Islamist movement

is traditionalist, and a revolt against modernity. Sivan describes Islamism as ‘a reaction against modernity’ (1985: 11). Likewise, Bernard Lewis (1988, 1993, 2002,2003

) and Moghissi (1999) contend that Islamism is hostile to modernity. A different version of this argument pleads that Islamism is an ‘authentic’ discourse untouched by modernity (Kelidar 1981; Davutoglu 1994; Sayyid 1997). In yet another version of this argument, Tibi avers that Islamism symbolizes the dream of ‘semi-modernity’ because, while it embraces the technological dimensions of modernity, it shuns the rationality of modernity (1995: 82). Based on the similar premise, Lawrence contends that Islamic fundamentalism is not only ‘anti-intellectual’ but also ‘anti-modernist’ (1987: 31, see also Ayubi 1991: 250). In Defenders of God: The Fundamentalist Revolt against the Modern Age, he makes a distinction between ‘modern’ and ‘modernist’. In his view, fundamentalists are ‘modern’ because they welcome ‘the instrumentalities of modern media, transport, or warfare’ and ‘relate fully to the infrastructures that have produced the unprecedented options for communication and mobility that today’s world offers’ (1995: 1). They are, however, not ‘modernist’ for they reject ‘modernism as a holistic ideological framework’ (ibid.:

17). Central to modernism, Lawrence writes, are the ‘values of Enlightenment’, ‘banner of secularism’ and ‘individual autonomy’ (ibid.:

6, 27). Though there are significant differences in the ways Tibi and Lawrence, as well as Lewis, Sayyid, Sivan and others,characterize

Islamism, they tend to broadly converge in their view that it is opposed to ‘real’ modernity or it is only partially modern as it disregards Enlightenment values and rationality.

I call the above line of argument into question. To begin with, the idea of ‘semi-modernity’ wrongly presumes that there is something else called ‘full modernity’. This, to me, appears to be a grossly quantitative rather than substantive argument. In what follows I make three interrelated arguments. First, I show that it is misleading to say that Islamism is adherent of traditions; opposed to and untouched by modernity or that its discourse is ‘authentic’ and ‘indigenous’. To illustrate my argument, I take the educational ideology of the Jama’at-i Islami (hereafter Jama’at, see below), as propounded by its founder-ideologue, Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi (1903–79), as a case study. I show that Jama’at’s educational ideology was characteristically modern. As a matter of fact, Maududi was never schooled in a traditional madrasa, Islamic seminary. As such, his corpus of writings begins with a ferocious assault on living traditions of Islam dear for ages to the majority of Muslims. Maududi indeed ruthlessly critiqued the relevance of the Islamic system of learning prevalent in India and elsewhere and urged Muslims to mimic the Western system wholesale, barring its values. Second, Maududi’s assault on traditions was accompanied by an ‘invention of tradition’ (Hobsbawm 1983; Eickelman and Piscatori 1996: 29) he called ‘pure’. Of his many inventions, the following stand out for their centrality in his total ideology of which education was only a part. Invoking the Qur’an and hadith, Prophetic tradition, he contended that Islam was a movement whose goal was to inaugurate an Islamic state or revolution. And Muslims, particularly his own party, the Jama’at, would work as the vanguard of pious, true Muslims to lead that movement towards its ultimate goal. Finally, in his view, the function of education was to fashion and provide the party with leaders and activists who were ‘pure’ Muslims.

Third, Jama’at’s ideology cannot be divorced from the issue of power.

Maududi’s primary concern was to rehabilitate the power Muslims had lost after the takeover of India by the British. In his reading of history informed by what I call ‘Islamist dialectics’,

the reason for Muslims’ decline lay in dilution, if not collapse, of pure Islam through jahiliyyat,

other of Islam. It was a result of jahiliat-infected education system, debased from the foundation of the Qur’an and hadith, that the rulers as well as ulama, clerics, got removed from pure Islam. Consequently, Muslims lost power. The only way they could regain it, he proposed, was to establish a ‘pure’ Islamic education system whose graduates would work as the vanguard of the Islamist movement for a future revolution. To this end, he called for a thorough change of the education system along the Western patterns because he held that the West derived its power from its superiority in education. To regain the bygone power, Maududi, like the aristocrat in Lumpeda’s penetrating novel of nineteenth-century Italy, The Leopard, who called for changing everything to retain the hold of aristocracy, urged Muslims to change every aspect of their education system.

This chapter is divided into three parts. In the first part, I outline the context in which the Jama’at was formed. I then move to unpack the links Maududi made between education, pure Islam and power. I end this part by showing how he urged Muslims to mimic Western education. Here I show his critique of the then existing madrasa education. In the following section, I deal with his opposition to a distinct type of modern education, especially his description of institutions such as Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), Aligarh, as ‘slaughterhouse[s]’. I then dwell on his alternative proposal and lay bare the sine qua non of Jama’at’s ideology according to which education was a technology to fashion an Islamic revolution/state. In the final part, I show the distinction of the Jama’at vis-à-vis the ideologies of other sects or groups. Here I also account for Maududi’s silence on institutions of sects or ideological collectivities such as the Deoband, the Ahl-i Sunnatwa

Jama’at (popularly called Barelwi by its rivals; hereafter Ahl-i Sunnat) and the Ahl-i Hadith. I end by showing that no other sect or ideological group shared what was the sine qua non of Jama’at’s educational ideology.

Loss of power, power of loss

I will start this part by briefly outlining the historical context in which Maududi’s ideas took shape and the factors that led to the formation of the Jama’at. Since he single-handedly propounded the Jama’at’s ideology, it would be helpful to have a biographical account, however sketchy, of his life. A basic familiarity with the political context and his biography will help the reader to appreciate the connections Maududi made between power, pure Islam and education.

Context and biography

During the 1930s and early 1940s, the Indian freedom struggle against British rule had entered a critical phase. Muslims were broadly divided into two streams. Led by the clerics of Dar al-Ulum, Deoband (henceforth Deoband) madrasa and the Jamiat-i Ulama-i Hind (both were almost synonymous), a majority of them were with the Indian National Congress that stood for a composite, secular and united India. Opposed to the Congress, the Muslim League advocated a separate homeland for Muslims. Maududi began his public life as a staunch Congressman. While still in his teens, he wrote panegyric biographies of M.K. Gandhi (soon confiscated by the British) and the Hindu revivalist leader Pundit Madanmohan Malaviya. He urged Muslims to emulate Malaviya: ‘Today all respect him [Malaviya] and he is venerable not only in the eyes of Hindus but he is also a great figure for us [Muslims] to follow’ (1992: 13). However, following the unceremonious demise of the Khilafat campaign in which he had enthusiastically participated, he grew disillusioned with the Congress–Jamiat-i Ulama alliance and moved away from the composite Hindu–Muslim nationalism to Islamism. In 1941, he formed the Jama’at-i Islami as an alternative to both the Congress and the League. His opposition to the League was, however, not whether or not a Muslim homeland be created but about its ideological content. Should it be based on democracy and ruled by Westernized Muslims or should it be based on sharia – caliphate

– ruled by ulama? Maududi was unambiguously for the latter (for details, see Nasr 1994, 1996; Ahmad 2005b: Chapter 3). The Constitution of Jama’at thus characterized its goal as the establishment of hukumat-i ilahiyya, ‘Allah’s Kingdom’ or ‘Islamic State’ (in Maududi 1942: 173).

It is clear that Maududi was greatly concerned with the recovery of Muslim power as he made its pursuit the very goal of the Jama’at. In fact, it mattered much more to him than many of his contemporary intellectuals because of the enduring historical ties of his family with the Mughal Empire on one hand and the Nizams of Hyderabad, the largest Muslim princely state in twentieth-century India, on the other. He grew up in Aurangabad, an important city of the princely state. After some years in Delhi and other North Indian towns, he went to Hyderabad where he lived until the late 1930s. The grandeur and spectacle of the Nizams notwithstanding, it was clear that in the vast sea that was India the Nizams had barely more than an island existence. Maududi grew up in the shadow of the ever-declining state of the Nizams and already extinguished Muslim power in Delhi. The sense of loss in him was total and it decisively shaped his ideas later. While there were many solutions to cope with the loss, such as the call of Sayyid Ahmad Khan, founder of the AMU, to embrace Western education, Maududi emphasized the rehabilitation of pure Islamic education for he thought that its corruption through jahiliyyat was the cause of the decline.

Purity and power

In Maududi’s diagnosis, the signature cause of the loss of power was the shaky foundation of Islamic civilization, tahzib, in India right from its beginning. During the first century of Islam, India was on the margin of dar al-Islam, the abode of Islam. The religious deviants and rebels challenging the central power of Islam had taken refuge there. That was why, he argued, remnants of those deviations and waywardness were still pervasive. During the eleventh century when the ‘real stream’ (the political stream) of Islam came to India, it was already polluted with the ‘dirt of ajam’,

non-Arab lands or cultures like Iran. In his view, most converts to Islam remained imprisoned in the practices of ‘jahiliyyat and polytheism’ prevalent before their conversion. Muslims who had come to India from outside were no different either. Since they were from ajam, central Asia, they too were ignorant of Islam. Their aim was to conquer lands and seek pleasure rather than follow pure Islam. Muslim civilization thus grew impure; it was an ‘amalgam of islamiyyat [Islam], ajamiyyat [non-Arabism] and hindiyyat [Indianness]’ (1937: 10). To Maududi, the Mughal emperor Akbar (1542–1605) was the greatest embodiment of impurity as he crafted an eclectic theology, din-i ilahi, by synthesizing the teachings of all religions, especially Hinduism (1940: 310–317). Hence his praise for Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi (1569–1624), a purist theologian who resisted Akbar’s eclecticism:

This [Akbar’s din-i ilahi] was the first great sedition (fitna) that sought to absorb Muslims in territorial nationalism by spreading atheism and irreligiosity. . Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi unfurled the flag of jihad precisely against this. It was the impact of that very impious era that gave birth to Dara Shikoh [Akbar’s great grandson who carried on theological eclecticism]. To eradicate this poison, Alamgir [popularly known as Aurangzeb, Dara Shikoh’s brother] struggled for fifty years. And this very poison eventually destroyed the political power of Muslims. (1938: 61)

Given this impurity, a truly sharia government was never established in India. The ulama too sided with the impure rulers, Maududi observed, to fulfil their worldly desires (1937: 9). The downfall of the Muslims was thus, he noted, imminent and natural. It had indeed already reached its acme during the seventeenth century. Had it not been for Aurangzeb’s Islamic zeal, Muslim power would have collapsed much earlier. With the death of the ‘last sentry of the Islamic fort’ (1937: 11), Aurangzeb, the hitherto invisible religious-moral weakness that had been growing for centuries beneath the surface became more prominent. Of all the Muslim rulers it was Aurangzeb alone whom he praised. All the rest, his argument implies, were steeped in jahiliyyat of one kind or another.

Maududi attributed the impure character of Muslims to their lack of knowledge about ‘pure Islam’. Throughout the Muslim period no concerted effort was made to impart pure Islam to the majority of people who converted to Islam. The then education system was along the lines later followed by the British. Its main objective was to generate the workforce to manage the state. The sciences of the Qur’an and hadith never became its foundation. The lack of pure Islamic education was the reason why, Maududi believed, Muslims lost power to the British (1937: 9–11; 1940: 314).

Education for power

The consolidation of the British rule after the revolt of 1857 only accentuated this impurity. According to Maududi, Muslims became much more corrupt and far removed from Islam due quintessentially to its anti-Muslim policy. The British particularly targeted Muslims. ‘Muslim principalities were destroyed and the legal and judicial system in practice for centuries was changed.’ The outcome was devastating. The ‘nation [Muslims] that once had the key to treasure’ was now ‘crying for a loaf of bread’. Muslims were deprived of the economic sources one by one.

‘And its [Muslim nation’s] ninety percent of population is now under the economic slavery of Hindus’ (1937: 46). The consequence of the British rule was as follows: ‘In this way during one and half a century Islamic power in India was thoroughly eliminated. And with the loss of political power this nation [Muslim] got mired in poverty, slavery, ignorance and immorality’ (ibid.:

11. Emphases added).

Two points follow from Maududi’s reading of history, and they seem to be in fierce tension. First, right from the beginning there was no ‘pure Islam’ in India. In a different context, he wrote that

ninety

nine percent individuals of this qaum [Muslims] are ignorant of Islam, 95 per cent are deviant and 90 per cent are adamant on deviance; which is to say that they themselves neither wish to follow the path of Islam, nor fulfil the objective because of which they have been made Muslim. (1999 [1944]: 290)

Neither did a truly Islamic government ever exist. Second, the British destroyed the Islamic power in India. The paradox is glaring. If there was no true Islam, 99 per cent of Muslims were deviant and never was a truly Islamic government ever established, how could the British have destroyed it? If the majority of Muslims were never pure and instead steeped in practices of jahiliat, as he so confidently argued, does not the figure of 90 per cent of Muslims under economic slavery of Hindus sound tension-ridden?

The umbilical link between education and power came out most eloquently in a lecture Maududi delivered in 1941 at Nadwat al-Ulama (hereafter Nadwa), a madrasa at Lucknow.

Four years later when the Jama’at met at its headquarters in Dar al-Islam, Pathankot (a village in Punjab), to put its ideology into practice, as the Jama’at’s amir, President, he presented his 1941 lecture as the foundation upon which to build the institutions in future (1991: 85). Given the monumental significance he himself assigned to it, it would be worthwhile to see whatwas the crux of his lecture

. Titled ‘New Education System’, Maududi praised the initiative for reforms of institutions under discussion during the 1930s. While applauding it he, however, warned the audience that mere patchwork reform would do no good today. Mocking the ‘progressivism (raushankhayali)’ of those who wanted to give English education to madrasa graduates, he stressed that this novelty had already become old. The need was not to replace a few old books by new ones, as reform was understood to imply. He argued for ‘total revolutionary reforms’ and overhauling of the entire education system so as to create an absolutely new one.

Questioning the piecemeal reform advocated by some, Maududi doubted if it would result in ‘restoring the world leadership to the ulama?’ In his view, there was an organic link between knowledge/education

and ‘leadership’. A people (giroh) that had the most superior form of knowledge also always became the world leader; it was the superiority of knowledge that made Greece and Europe world leaders in different epochs of history (1991: 56–57). The reason why Muslims were ‘dislodged from the leadership (imamat)’ was because they could not compete with the West in mastering knowledge. Distrustful of any divine role, he asserted that whosoever, whether atheist or believer, possessed the most superior knowledge would become the world leader. What did he mean by knowledge, however?

Sources of knowledge and historical lag

According to Maududi, ilm meant ‘to know’. He used it in a strictly worldly sense. Based on this definition, he identified three sources of knowledge in the Qur’an: aural,sama

, observational, basar, and inductive, the ability to deduce results from the first two, fawad. Compared to others, when and if a given group – whether atheist or believing – acquired the best command over education in its entirety, it had ruled the world throughout history and would rule it in the future as well. This, to him, was the guiding principle behind the rise and fall of nations. However, he put greater emphasis on basar and fawad than on sama, (ibid.:

57–58) because the first two were directly pertinent to worldly affairs. When a mighty nation/people began to fall, he presented it like a natural law; it tended to confine its education to aural methods and close its doors for reforms and additions. Such a nation was doomed to collapse. A new nation armed with the most sophisticated control over all the three sources of knowledge then took over the world leadership.

Maududi’s conceptualization of ilm and promulgation of law (zabta) of the rise of nations based on the superior command over the former by the latter radically departed from Islamic traditions. In a challenging paper, Israr Ahmad, formerly one of the editors of the Jama’at’s English organ, Radiance, argued that Maududi’s ideology was ‘in spirit Western’ (1990: 54). I would mention three elements of his critique. First, historically, ulama conceived ilm in a primarily religious sense. That is to say, ‘to know’ was to know and believe in God. From this perspective, the three sources of knowledge – aural, observational and inductive – might not necessarily and always aid in knowing or believing in God. Rather they might foster doubts in knowing God and hence might prove lethal. Moreover, ilm was always tied to the success in the life hereafter rather than worldly domination, which was Maududi’s prime concern (ibid.:

41, 49). Second, Maududi wrongly interpreted leadership in a worldlypolitical sense. Ahmad contended that the sense in which the Qur’an used imamat was in the sense of Muslims being the best of all peoples (khair-i ummat) in that they possessed the divine truth.And through the Qur’an Allah guaranteed that they would do so for good.

To Ahmad, therefore, there was no question of Muslims being dislodged from the leadership in so far as they alone held the divine truth. To say that would be to distrust the Qur’an. As for the leadership in the political domain, he argued that the Qur’an considered it neither desirable nor necessary (ibid.:

33–37). Third, he saw no necessary link between knowledge (not in Maududi’s sense) and leadership. It was rather the other way round. In his reading of the Qur’an and what he called ‘historology’, divine history, many a politically dominant people (qaum) stood condemned in the eyes of Allah because they flouted His will, whereas the politically weak ones were praised by Allah because they followed Him and had the right knowledge (ibid.: 37).

Mimic the West

Ahmad’s critique of Maududi perfectly fits in the larger framework that I have outlined. Much like the four Qur’anic words – ilah (God), rabb (God), ibadat (worship) and din (religion) – which he had politicized and secularized,

Maududi also interpreted ilm and imamat in a strictly political sense and imposed on them the meanings of the then dominant ideologies. Again, there was no role for Allah to play; a people (even if atheists) would become the world leader regardless of His grace if only they could acquire the most superior form of knowledge. It is to be noted that Maududi did not believe in dajjal, anti- Christ, either. Since his reference point was always the dominant West and how Muslims could compete with it, he urged Muslims to imitate the West and overcome the historical lag because of which they had lost power. Comparing the salutary achievements of the ‘atheist West’

and failure of Muslims in education which made the former a world leader and the latter a mere follower, or subjugated, or both, he wrote:

By contrast, the God-rebelling Europe progressed in education. It used aural knowledge more than you did. In observational and inductive fields too Europe has made all the contributions in the last three centuries. Its obligatory outcome had to be . that it [Europe] became a leader and you [Muslims] a follower. (1991: 60)

If Muslims today wanted to regain the world leadership, Maududi urged, they had to acquire more efficient mastery over all sources of education than Europe had. He wondered why Shah Wali Allah (d. 1762) and his son, Shah Abd al-Aziz (d. 1824), two of the most important revivalist scholars of their times, did not send a delegation of ulama to Europe to discover the ‘secret of its power’ and what ‘we lacked in comparison to it [Europe]’ (1940: 345). He offered a long list of philosophers whose contributions had made Europe a world power – Fichte, Hegel, Comte, Schleiermacher, Mill, Quesnay, Turgot, Adam Smith, Malthus, Rousseau, Voltaire, Montesquieu, Thomas Paine, Darwin, Goethe, Herder, Lessing, etc. Comparing their contribution with that of Muslims during the same period, he concluded that the latter’s had not been even 1 per cent (1940: 342–346). His call to Muslims was obvious: master the Western sciences and knowledge so as to overtake – and overtake they must – the ‘hell-inviting atheist world leadership’ of the West and restore it to the ‘paradise-bound, Godknowing’ Muslim leadership.

Maududi’s call to mimic the West went hand-in-hand with his resounding critique of the traditional Islamic education system in which he found three basic demerits. To begin with, for ages it did not use observational and inductive methods of ilm. The aural method was also limited only to acquiring already accumulated knowledge. He described the continued insistence on the aural method and refusal to employ observational and inductive methods as a common mistake of ‘all the centers of Islamic education’. Both the Nadwa and the Jamia Azhar of Cairo introduced some reforms, but they too did not go far enough. The net outcome of their reform, Maududi stated, was that they expanded the aural method to include contemporary knowledge. But observational and inductive methods remained suspended in both the seminaries (1991: 60). Lamenting such partial and half-hearted reforms, he predicted that they would never enable Muslims to compete with the West and regain the leadership:

The maximum benefit of this knowledge [reformed curricula at the Nadwa and the Azhar] would be that you become an excellent, rather than a worse, follower. You would not get leadership, however. All the reform proposals that I have seen till now can only make you a better follower. No proposal has been conceived so far that makes you a leader. (ibid.:

60)

Second, there was a glaring absence of specialization in Islamic seminaries. They produced generalists of all subjects rather than specialists of one. The existing tradition to make every student a ‘maulana (cleric)’ should be done away with (ibid.:

72). Third, most seminaries did not teach new subjects. Responding to a proposal that every maulwi (theologian) be taught English, Maududi said that that was far from sufficient. He was in favour of the introduction of not only English but other sciences as well.

Modern subjects, he pleaded, must figure in the curricula. But not in the way the Nadwa or the Azhar had incorporated them. By merely adding them to the curriculum, he argued, no revolution can be brought about in the leadership. The West had produced the sciences, both natural and social, with its own God-denying values. Teaching them, along with the traditional sciences, exactly the way they were available then would create a split in the minds of the students. Influenced by Islamic sciences, some would become ‘maulwi’, influenced by Western subjects, while others would become westerner, rather than comrade (ibid.:

68–69). The need, therefore, was not to add modern subjects as an appendix to the old curriculum of theology ‘but to turn all subjects [Western sciences] into a course of theology’ (ibid.:

71). He argued that the madrasa system must undergo ‘total revolutionary reforms’ to adopt all the elements of the Western education that had the following aspects: sources of knowledge, methods of imparting knowledge, facts and, above all, values accompanying them. Maududi argued for the adoption of all the elements barring values because he regarded them as amrit, elixir of life; he pleaded to shun the values because they were ‘poison’. The Western values were poison because they were based on atheism, and consequently, humans in the West had turned immoral, materialist,selfish

and so on.

So far I have demonstrated that in Maududi’s analysis the reason why Muslims lost power was because they had turned away from pure Islam and embraced jahiliyyat. The emperor Akbar was a quintessential example of the impurity. With the solidification of the British rule, the impurity further exacerbated and Muslims eventually lost whatever power was left them. To Maududi, there was an organic link between education and power. Based on this assumption, he concluded that the reason behind the rise of the West as the world leader was that during the last three centuries it had developed the most superior command over the sources of knowledge. If Muslims desired to compete and vanquish the West, he stressed that they must mimic the Western system of education. I conclude this part by depicting his critique of the Islamic education system, which he found fully out of tune with the challenges of the modern age.

New alternative

In the second part of this chapter, I discuss the contours of the alternative system Maududi proposed. However, it seems relevant here to elucidate first how he saw modern education prevalent among Muslims then. In the previous section I showed that one of his criticisms of institutions like the Nadwa and the Azhar was that they had incorporated Western sciences without Islamizing them. This precisely was the ground on which he also attacked colleges and universities like the AMU that Muslims had founded along the Western line. To Maududi, rather than only borrowing facts from Western education they had also blindly borrowed its values. Such institutions were, he noted with a sense of rage, therefore, producing ‘black Englishman’ rather than pure Muslims. More importantly, they had no goal of establishing Allah’s Kingdom. In a phrase that became a metaphor in the Jama’at’s language, he called Muslim colleges and universities ‘slaughterhouse[s]’.

College as ‘slaughterhouse’

In an article written in response to a proposal of the AMU Court, Maududi spelled out his position on modern institutions. The AMU Court had set up a committee to recommend modern means of education and revision of the syllabi of Islam so as to make their ‘teaching more satisfactory’ and foster an Islamic spirit in students. Maududi’s response to the committee was a damning critique of the very rationale of the AMU. He stated that if the purpose of its establishment was only to impart modern education there was no need for it. The universities of Agra, Lucknow and Dhaka were well equipped for it. In his opinion, it was founded to give modern education and make students Muslim at the same time. Since other universities did not meet this need, the AMU was established and hence it was called ‘Muslim University’. However, he found no difference whatsoever between the graduates of the AMU and those of other (non-Muslim) universities. Since its inception, the AMU had failed, he complained, in meeting this objective.

The number of students who graduated from this university with an Islamic viewpoint . is perhaps even less than 1 per cent. . It is sad that the existence of a large number of . products and those currently studying isnot only not beneficial

but is rather harmful for the Islamic civilization. . Among them there is not only indifference to religion but also a sense of hatred. The frame of their mind has been cast in such a manner that they have gone beyond doubt and reached a stage of disbelief. And they are rebelling against those principles on which lies Islam’s foundation. (1991: 9, italics mine)

Maududi cited a private letter of one of its alumni to support his argument. To add weight to his argument, he called the letter a ‘real reflection of university’s inner reality’. Once under the spell of communism and Western culture, but later seemingly returned to Islam, the alumnus regarded ‘Westernism’ (maghrabiyyat) as a ‘dangerous thing’. ‘In this center of Islamic India [AMU] there are a significant number of students who have become apostates and turned . apostles of communism,’ he wrote. Soon after citing the letter, Maududi offered his own judgement that it is ‘giving results against the objectives’ for which Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan had established the AMU (1991: 10–11). From the quotation it thus appears that Khan had founded the AMU precisely for the purpose Maududi wanted it to serve. It was a tactical move. Like Maududi later, Khan was surely concerned with the downfall of the Mughal Empire and wanted Muslims to be on a par with the Hindu middle class. But his project, unlike Maududi’s, did not envisage Allah’s Kingdom (Nizami 1966). Indeed, his reading of Islam along the lines of European rationalism only irked the established orthodoxy. He was branded as ‘nacheri’, naturist, and ‘kafir’ (Lelyveld 1978: 110–111, 130–134). Not surprisingly, only four pages later the tactics gave way to an open assault on Khan.

Setting aside the metaphorical language, now I will say something straight. The temporary objective of the educational movement launched under the leadership of Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan (God forgive him) was to enable Muslims to better this world according to the needs of modern age. (Maududi 1991: 15)

Maududi’s opposition to Khan and his educational movement is clearly evident from the phrase ‘God forgive him’. Such a phrase is often employed when someone is considered impious. It is hardly unambiguous that in his view Khan had seemingly committed a sacrilegious act of sorts.

This

indeed was the case. In a different context, he wrote that the ‘ancestry of all the deviations that had cropped up in Muslims after 1857 directly or indirectly went back to the personality of Sir Sayyid [Ahmad Khan]’ and that ‘he died after having damaged the mindset of the entire Muslim community’ (in Nu’mani 1998: 92). He described Khan as ‘the foremost imam of Westernism (tajaddud)’. Continuing his assault on Khan, Maududi added:

This movement [Sayyid Ahmad Khan’s] has definitely bettered our world to an extent. But it has destroyed our religion (din) more than it has built our world (dunya). It has produced black Englishmen (firangi) among us. . It has sold the upper and middle strata of ournation,

both externally and internally . off to the materialist civilization of Europe. (1991: 16, emphasis added)

Maududi believed that the AMU should meet the objective of producing leaders to establish Allah’s Kingdom (1991: 28). It was, however, on the contrary serving Western culture both through its curriculum and extra curricular activities (ibid.:

26). As for the former, Western sciences were being taught in such a way that students’ minds too turned Western. They came to believe that if there was a proper and valuable thing in the world it was only that which accorded with Western principles (ibid.:

22–23). As for the latter, dress, sports and overall environment at the AMU was ‘95 per cent, if not fully, definitely Western’ (ibid.:

23). To add a contextual note, Maududi’s grandfather had recalled his father from the AMU because he had played cricket there wearing ‘infidelic [kafir] dress’ (1979: 30). Since Maududi considered institutions like the AMU to be wholly against his Islamist project, he urged Muslims not to go there. In a convocation address delivered in 1940 at Islamia College,

Amritsar, he fearlessly articulated his hostility to Western education. While delivering it, he thanked the college for inviting him despite knowing that he was a ‘great enemy of the education system under which this great college is founded’ (1991: 44).

Asking the audience to bear with his unpleasant but true feelings, he said:

In fact, I consider your mother college – and not only this college but also all such colleges – slaughterhouse (qatlgah) rather than education house. In my view, you have been slaughtered here and the degrees that you are about to get are indeed death certificates. (1991: 45, emphasis added)

The metaphors of ‘slaughterhouse’ and ‘death certificates’ became so powerful that many students under Maududi’s influence left the AMU (and other modern colleges), considering it un-Islamic to study there. Indeed, until the late 1950s, the Jama’at imposed a ban on its members to study at such institutions. Soon after Partition, the Jama’at set up an alternative institution for those who had left colleges and universities. In what follows we will see what kind of alternative education Maududi had in mind and how it was different both from madrasas on the one hand and modern universities such as the AMU on the other.

Features of the alternative

Dissatisfied with both the Nadwa and the AMU, as demonstrated in the preceding pages, Maududi offered his own alternative. He presented it in two articles and one lecture: first, in his 1936 critique of the AMU education, second, in a clarification about the critique, but, more importantly, in his lecture at the Nadwa. Since these pieces were written or delivered on different occasions with different types of audience, the emphasis was varying, as was the style.

However, there was a unity of purpose informing them all. Maududi’s alternative had the following major features:

•make

education mission-oriented;

• abolish the distinction between religious and secular sciences (ergo, between religion, din, and world, dunya);

•following

from the second, Islamize all sciences; and

• introduce specialization

Of all the features of his alternative, Maududi regarded having a mission as the most important. Both teachers and the taught should have a mission, and he lamented that graduates of modern education rarely had one. He likened aimless students with animals because the latter had no mission (ibid.:

50). What should be the objective of education, then? As Muslims, the mission of students was to wage a greater jihad for the formation of Allah’s Kingdom. And the objective of the education system was to prepare the ‘ground to bring about an Islamic revolution’ (Tarjuman al-Qur’an

1941, June–August: 477). The mission had to be fostered in all possible ways, including through sports and recreation. The product of the new system would be a ‘mujahid in the path of Allah’ (1991: 79).

Among

others, this was arguably the unique feature of Maududi’s alternative.

He stated that, since no other system in the whole of India had such a mission, the Jama’at had no option but to establish its own. In other words, its objective was to manufacture a ‘leader’ and workers for the Islamist movement (ibid.:

86–87). So central was the mission to him that he warned the Jama’at members not to make the running of institutions an end initself

. If they became the end rather than the means for the ultimate mission, he advised them to destroy such institutions as the USSR had destroyed their own industrial centres during the Second World War to safeguard its ideology (1944: 54).

The rationale behind dissolving the distinction between religious and secular education was that, if maintained, it would turn the minds of the students into ‘a battle ground’ for the conflict between Westernism, firangiyyat, and Islam (1991: 24). Anticipating the religious commitment of the students produced out of this curriculum, he said, ‘Your products would be non-Muslim in philosophy, science, laws, politics. . And their Islam would get limited to a set of mere beliefs and religious rituals’ (ibid.:

35). Maududi’s opposition to the secular–religious distinction was also premised on his novel theorization of Islam as an organic whole. For him, Islam was a complete, inseparable system of life, which, unlike Christianity, did not maintain the distinction between world and religion. Since the AMU reproduced this distinction, it went against his Islamist definition of Islam. Instead of attaching theology as appendix to the Western sciences, as in his view the AMU did, he called for a theologization of entire sciences (1991: 27, 71). Once that had happened, he noted that there would be no need for a separate subject of theology. Indeed, he said that examinations for graduates of theology should be abolished. Instead of domesticating Islam to the department of theology, he argued for Islam to dominate all subjects (ibid.:

35–36).

Based on the above, in his 1941 lecture, he proposed the specialized pursuit of knowledge because it was impossible to teach the ever-increasing knowledge in its entirety to every student. He envisaged four faculties for Western sciences: faculties of philosophy, history, social sciences and natural sciences.

In all those faculties, the Qur’an-based viewpoints of philosophy, history, society and civilization, and nature were respectively to be taught so as to refute the views on those themes of the Western sciences, other religions such as Hinduism or deviant schools within Islam like Sufism. Anti-Islamic thought should also be taught to show that it was the philosophy of the condemned and the misguided.

The guiding framework to teach all subjects would be to prove that Islam was the only true and viable system of life and that it was superior to all (1991: 72–79). There should be a faculty for Islamic sciences subdivided into departments for the study of the Qur’an, hadith and Islamic law. The last one would be the most important, for it would show the way other departments would function under an Islamic framework.

Situating the alternative

In the preceding pages, I discussed the distinct features of Maududi’s alternative ideology. In the final part, I intend to place Jama’at’s alternative in relation to the larger discourses on education by different collectivities of Muslim society. My aim in undertaking this exercise is to show the distinction of the Jama’at ideology vis-à-vis the ideologies of other sects and groups already alluded to, such as the Nadwa and the AMU. However, I will also account for Maududi’s silence on sects and/or ideological collectivities such as the Deoband, the Ahl-i Sunnat and the Ahl-i Hadith. I will end by showing that no other sect or ideological group shared the sine qua non of Jama’at’s ideology, according to which education was an instrument of heralding an Islamic revolution/state.

New ship, new captain

In his 1936 article on the AMU, Maududi employed the metaphor of a ship to attack both the traditionalist and modernists and to foreground his own alternative. Taking 1857 as a benchmark, he said that two groups emerged to save their sinking ship in its aftermath. The first group (i.e. the traditionalists) sought to repair the old ship; the second one (i.e. the modernists) ‘rented’ a new one, the Western ship. He was critical of both. The first one, he said, was incapable of competing with the Western ship because the traditionalists were following the same old path charted long ago. He asked them to give up blind imitation, andhi taqlid, and instead do ijtihad (interpretation based on reason). ‘A real leader . is he who adopts, subject to time and occasions, most proper ways using his power of ijtihad’ (1991: 13–14). His call for ijtihad was reflected in his rejection of all the existing corpus of texts on Islam and the need for writing new ones.

On the principles of fiqh [jurisprudence], commandments of fiqh, Islamic economics, sociological principles of Islam and hikmat of the Qur’an there is an urgent need for writing modern books . as the old book are no longer relevant for teaching. . People of ijtihad may find good materials in them but teaching them exactly as they are to students of contemporary age is absolutely useless. (ibid.:

40)

He repeatedly urged the recasting of Islam so that it appealed to the ‘minds and psychology of boys and girls of this age’ (1991: 38). This he sought to do by way of restoring the ‘real spirit of Islam’. Dissatisfied with the available books, he wrote, ‘For this purpose you will not get a ready made syllabus; you have to make everything anew’ (ibid.:

18). The most radical element in Maududi’s ijtihad was the direct reading of the Qur’an in Arabic and then its application to the problems of the world. ‘To understand the Qur’an there is no need for any of its interpretation (tafsir)’ (ibid.:

38, 54). From this perspective, he found the captains of the old ship steeped in blind imitation. In the name of so-called ijtihad, he said, the traditionalists had added a few electric bulbs to the old ship and pretended that it had become new (ibid.:

14). As such, it was incapable of facing a terrrible storm (of the West). A single wave may sabotage it completely.

The other ship, ‘rented’ by the modernists, was more up-to-date and capable of competing with the Western ship. The danger, Maududi feared, was that it would lead Muslims, as indeed it already had done in his opinion, away from the Islamic ‘destination’ (1991: 13). To fool themselves and Muslims at large that it was an ‘Islamic ship’, the modernists had employed a few Muslim captains. But in fact it was not. The rented ship was ‘more dangerous than the old ship’ as it would alienate Muslims in a single stroke and turn them into Englishmen, comrade or apostate. Having shown the demerits of the old and new ships, Maududi asked Muslims to get down from both and manufacture a ship of ‘their own’. The new ship, he proposed, would be armed with the latest Western technologies but its design would be of a ‘purely Islamic ship and its engineers, captains and watchdog all would be familiar with ways of destination of the Kaba’ (ibid.:

15).

Educational spectrum

The metaphor of old and new ships, it is not difficult to dissect, symbolized the Nadwa and the AMU respectively. They referred to two points on the educational spectrum characteristic of Muslims during that period: Nadwa as a symbol of traditionalism and AMU of modernism. Though the Nadwa stood for reform, it was unprepared for the ‘total revolutionary reforms’ Maududi desired. That was what he meant by a few electric bulbs that the Nadwa had added and pretended that it had a new ship. Applauding it for its reform initiative and simultaneously critiquing it for its insufficiency leaves one crucial question unanswered. What did he think of the Deoband and madrasas of Ahl-i Sunnat sect/ideology?

In his book, Ta’limat, Maududi did not even mention the Deoband. Why this silence? In the wake of the 1936 provincial elections, he had attacked Hussain Ahmad Madani, head of the Deoband madrasa, for lending unstinted support to the Congress and opposing the League. Based on his Islamic notion of united nationalism or nationhood, he had pleaded for a joint Muslim–Hindu struggle against the British (Madani 2002 [1938]). In Maududi’s view, Madani was distorting Islam and making Muslims hostage to the Hindu majority (Maududi 1938). Given his fierce opposition to the Congress and Madani, it was only expected that he would ignore the Deoband madrasa. An equally important reason seemed to be the Deoband’s opposition to Western sciences. Though it had incorporated ma’qulat, rational sciences (philosophy, logic, etc.) in its syllabus, its balance was tilted towards manqulat, transmitted sciences (e.g. the Qur’an and hadith). Sociology, economics, history, English and pure sciences were not part of its curriculum. Its method of teaching and acquiring knowledge was still aural. Such a curriculum bereft of ijtihad, as Maududi argued, could hardly compete with and beat the West. Additionally, despite its call to revive pure Islam, the Deobandischool

did not fully break off from Sufism. The emphasis on close relations between student and a chosen spiritual guide was in fact a crucial feature at Deoband (Metcalf 1982: 265–267). Maududi’s description of popular Islam as jahiliyyat and of Sufism as ‘opium’ (1940: 340) would have hardly made him look towards the Deoband. For the same set of reasons he also did not mention the madrasas of the Ahl-i Sunnat sect. In two crucial treatises, ‘Renewal and Revival of Religion’ (1940) and ‘Islam and Jahiliyyat’ (1941), he had the dubbed core beliefs and practices associated with the Ahl-i Sunnat sect polytheistic and signs of jahiliyyat. Compared to the Deobandis, the Ahl-i Sunnat sect was clearly a far more ardent supporter of popular, customladen, Sufism-oriented, ritualistic Islam (Metcalf 1982; Sanyal 1999) or what Gellner wrongly calls ‘Low Islam’.

Also, it was least, if at all, open to ijtihad.

In contrast to the Deoband and the Ahl-i Sunnat madrasas, the Nadwa, the venue of Maududi’s 1941 lecture, was closer to his alternative. Established in 1893, the key idea behind the formation of the Nadwa was to work as a mid-way between the modernism of the AMU and the traditionalism of the Deoband (Agwani 1992: 357; Ansari 1995; Hasani 1997a: 48). Shibli Nu’mani, a close associate of Sayyid Ahmad Khan at Aligarh, was one of its founding fathers. Later, Nu’mani parted ways with Khan’s modernism, left Aligarh and helped establish the Nadwa (Lelyveld 1978: 247–248). The founders of the Nadwa were uncomfortable with the AMU’s exclusive focus on modern subjects, with Islam having just a decorative presence (Akbarabadi 1995: 186) in its syllabi.

They were equally unhappy with the Deoband madrasa because it focused primarily on traditional subjects to the neglect of the modern sciences (Zaman 2002: 69). Nadwa thus introduced English, history and geography in its curriculum (Hasani 1997: 47–54). It was the first madrasa designed to meet the need for a reformed Islamic syllabus in the late nineteenth century.

As such, the Nadwa was more inclined toward reform and Western subjects. Moreover, it was more puritan in its beliefs than both the Deoband and the Ahl-i Sunnat madrasas. Put differently, Islam in the rendition of Nadwa’s ideology was, if not fully pure as Maududi desired, less contaminated with jahiliat than that of the Deoband and the Ahl-i Sunnat madrasas. That was why he applauded the Nadwa. For his educational agenda to unfold, Maududi did not find any other madrasa more appropriate than the Nadwa (1991: 55). His opposition to modern colleges in general and the AMU in particular pushed him more towards it. Given this distinct orientation of the Nadwa, Maududi was able to win support there first. His articles on the contemporary issues in Tarjuman al-Qur’an had deeply influenced Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi, then a young student at Nadwa and later to become its rector and a world-famous theologian, and Masud Alam, both of whom later joined the Jama’at. Nadwi had already met Maududi in 1939 at Lahore. In a letter to Nadwi, the latter had requested him to look for someone who could translate his book Purda (The Veil) into Arabic, for sale in Arab countries. To do this work, wrote Maududi, my ‘eyes do not look towards any other center except the Nadwa’ (Nadwi 2000: 304). Moreover, it was Nadwi who had invited him to deliver the lecture at the Nadwa. In 1941 when the Jama’at was formed, Ali became amir of its Lucknow unit.

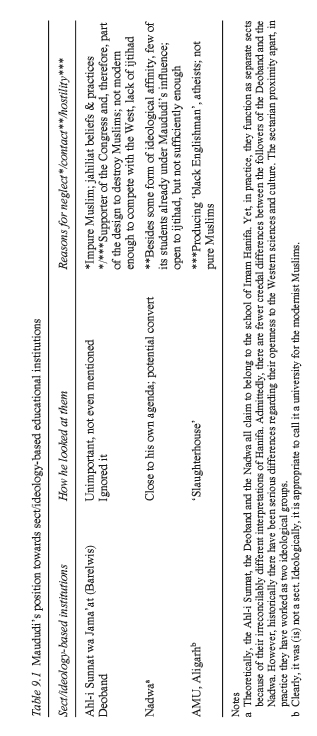

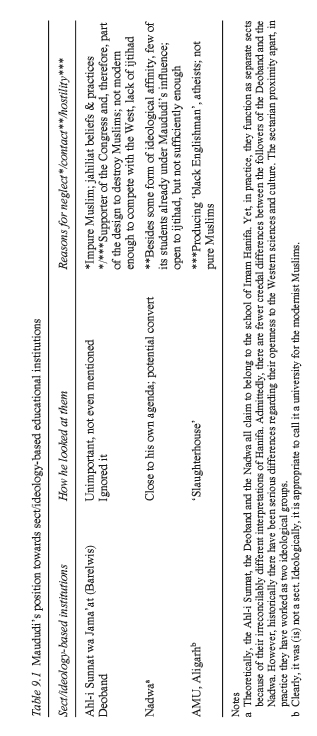

Table 9.1, based on Maududi’s educational ideology and the proposed alternative, shows his ideological position vis-à-vis the educational institutions of other sects/ideologies.

Table 9.1 synoptically presents Maududi’s position towards the then-known institutions and why he referred to some of them and maintained silence about others. In the remainder of this chapter, I intend to show that no other sect/- ideology-based educational institution shared the goal that the Jama’at had set for itself, namely the pursuit of an Islamic state.

Table 9.1 Maududi’s position towards sect/ideology-based educational institutions

Notes

a

Theoretically, the Ahl-i Sunnat, the Deoband and the Nadwa all claim to belong to the school of Imam Hanifa. Yet, in practice, they function as separate sects because of their irreconcilably different interpretations of Hanifa. Admittedly, there are fewer creedal differences between the followers of the Deoband and the Nadwa. However, historically there have been serious differences regarding their openness to the Western sciences and culture. The sectarian proximity apart, in practice they have worked as two ideological groups.

b

Clearly, it was (is) not a sect. Ideologically, it is appropriate to call it a university for the modernist Muslims.

State, Islam and education

Though some argue that the Deoband was founded to compensate for the defeat Muslims suffered in the anti-British revolt of 1857 to regain Mughal power, and hence it had political ambition (Ahmad 1997: 19), afterwards it barely nursed any desire to regain the state (Metcalf 1982). This is not to say that it ceased to be political. Far from it – it grew more political, especially with the onset of the Congress-led non-cooperation and Khilafat mobilizations. But like the Congress, the Deoband unflinchingly believed in a secular India based on the composite nationalism of Hindus and Muslims (Madani 2002; Shahjahanpuri 2003).

Neither in theory nor in practice did it ever desire caliphate. Thus, soon after independence in 1947, the Jamiat-i Ulama, the political wing of the Deobandi school,

stated that it would no longer play a political role now that its objective of India’s independence had been met. Further, it said that in future it would limit its role to religious reform and advancement of the rights of Muslims (Dastur of the Jamiat-i Ulama-i Hind undated: 2).The

same was true for the Nadwa. In spite of some affinities with Maududi’s alternative, the pursuit of a sharia state did not figure in its agenda. Contra Maududi, Shibli Nu’mani, a prominent leader-theologian of the Nadwa, indeed argued that Islam did not require a state and that Muslims ought to be ‘loyal and obedient to whatever government they are under’ for that was the ‘teaching of Islam, as . enunciated in the Qur’an, hadith, fiqh and all’ (1999: 161). Following India’s independence, the Nadwa also firmly believed in Indian secularism and democracy. As its agenda-setter in post-Independence India, Nadwi took pride in the Muslim civilization being an amalgam of Islamic and Indian influences. Though initially a Jama’at member, for him, unlike Maududi, the amalgamated Indian Muslim civilization was ‘a matter of beauty’ (Nadwi 1992: 96).

The pursuit of a state did not constitute the agenda of the Ahl-i Sunnat sect either. Unlike Maududi, its ulama did not consider the state to be central to Islam (Kachhochhvi 1997: 298). As its supreme leader, Imam Ahmad Riza Khan (d. 1921) did not support the Khilafat campaign for the restoration of the Turkish caliphate. And unlike the Ahl-i Hadith ulama (see below), a prominent figure of which had, in 1803, declared India dar al-harb, abode of war, Ahmad Riza Khan instead regarded it dar al-Islam, the abode of Islam (Sanyal 1996: ch. IX). The prime concern of the Ahl-i Sunnat was to combat the flood of reformism of the Deoband, the Nadwa, the Ahl-i Hadith and the Sayyid Ahmad Khan-led Aligarh movement, which it regarded as an assault on its version of pure Islam (Rizwi 2001: 13). The objective of its madrasas in colonial India was to combat the impurity of its rival sects (Sanyal 1996). In post-colonial India also, the objective remained the same. As its central madrasa, the goal of the Jamia Ashrafiyya (in the Azamgarh district of Uttar Pradesh (UP); formed in 1972) was to spread its version of authentic Islam and combat the deviations and falsehoods of its rivals (Jamia Ashrafiyya undated).

In contrast to all the sects mentioned above, the state had been historically central to the Ahl-i Hadith sect (known as Wahhabi to its rivals). Though it took an organizational shape only in 1906 with the formation of the All India Ahl-i Hadith Conference (Akbar 1999: 320), its leaders traced its genealogy to Shah Wali Allah (Ghazipuri 1999: 77). It was his son Shah Abd al-Aziz who, in 1803, had declared India dar al-harb. Since the first quarter of the twentieth century, the Ahl-i Hadith ulama, however, began to acknowledge the infeasibility of turning India into dar al-Islam. Some joined the Congress while others joined the League (Ghazipuri 1999: 79). They, therefore, exclusively focused on attacking their rival sects in the name of pure Islam (Rahmani and Salafi 1980: 15; Ghazipuri 1999; Salafi 2004). After India’s independence, its central madrasa, Jamia Salafiyya, was established in Banaras, UP, in 1963. Of its eight objectives, none mentioned an Islamic state. Its central objective was to spread puritan Islam by ‘eliminating all innovations (bidat) and superstitions, false customs and traditions, wrong creeds and ideologies’ which have spread among Muslims as a result of their ‘intermingling with non-Muslims and the Western onslaught’ (Rahmani and Salafi 1980: 103–104).

Conclusion

Taking Jama’at-i Islami and the educational writings of its founder-ideologue, Maududi, as a case study, I have shown the fallacies of arguments made by scholars like Lawrence, Sivan, Moghissi, Lewis, Sayyid and Tibi who assert, though with varying degrees of emphasis and significantly different angles, that Islamism is ‘anti-modernist’, a revolt against or hostile to modernity. I have argued that it is wrong to call it an ‘authentic’, ‘indigenous’ discourse untouched by modernity. As a matter of fact, Maududi did not have a madrasa education. On his graduation from the secular-composite nationalism of the Indian National Congress–Jamiat-i Ulama alliance to Islamism, he began to mount a ferocious attack on madrasa education and the ways of teaching Islam therein. Thus, rather than being an adherent of tradition, he attacked it. He stressed that the traditional madrasas were no longer relevant. He stood for its ‘total revolutionary reforms’ and expressed the need for a new, pure Islamic system. In so doing, he invented tradition. His most important invention was that Islam was an eternal movement with a divine goal to establish hukumat-i ilahiyya, Allah’s Government or the Islamic state/revolution, and Muslims were a party of the vanguard to lead that movement towards its ultimate goal. This realization led him to form the Jama’at-i Islami, whose objective he defined as the establishment of Allah’s Kingdom. I demonstrated that the Jama’at’s goal of an Islamic state was rooted in a historical context in which Muslims had lost power to the British. The aristocratic family lineage of Maududi played an equally important role in determining the goal of the Jama’at.

In the Jama’at’s discourse, education figured as an instrument of rehabilitating the power Muslims had lost to the British/theWest

. Maududi believed that Muslims lost power because they had deviated from pure Islam and embraced jahiliyyat, the ‘other’ of Islam. To regain power, he called upon Muslims to shun jahiliyyat and fashion a pure Islamic education system whose graduates would work as leaders and activists of the Islamist movement to herald an Islamic revolution. Since his concern was always the dominant West, he asked Muslims to embrace Western education wholesale, except for its values. Maududi’s call to embrace Western education stemmed from the belief that the West derived its dominant position from its superiority in knowledge. If Muslims were to beat the West and regain the dominant position, he urged them to imitate Western education. It was for this reason that he lamented the slow pace of reforms at madrasas like the Nadwa in India and the Jamia Azhar in Egypt. He found the old books taught in madrasas ‘useless’ and emphasized the need for writing new ones for the modern age. While he attacked the traditional madrasas for their ‘blind imitation’ of tradition and the lack of ‘ijtihad’, this did not mean that he endorsed the agenda of the modernists like Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan who introduced Western education and founded the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU). Maududi called such modern institutions ‘slaughterhouse[s]’ and its degrees ‘death certificates’. Indeed, he held Khan responsible for all the recent deviations among Muslims. He attacked Western educational institutions for two reasons. First, he held that they were making their students ‘black Englishmen’, apostates, ‘comrades’ rather than pure Muslims. Second, they did not have any agenda of pursuing a sharia-based state, which he considered to be the divine objective of Islam.

The sine qua non of the Jama’at’s ideology was that pursuit of the state was the main objective of a pure Islamic education. I concluded by showing that the educational institutions of none of the other ideological groups or sects among Indian Muslims, including those of the Ahl-i Hadith sect, had this objective. In this respect, the Jama’at stood alone and is unique. By way of a final remark, I would like to add that while it is important to take into account the ideology of a movement such as the Jama’at, it is much more important to empirically study how an ideology is put into practice. In the case of the Jama’at in post-colonial India, its practices diverged from its ideology to the extent that ideology itself got astonishingly transformed. However, this is a subject beyond the scope of this chapter.

Notes

0%

0%

Author: Jamal Malik

Author: Jamal Malik