4: MADRASAS

The potential for violence in Pakistan?

Tariq Rahman

IntroductionThe

madrasas of Pakistan have been making headlines since 9/11 when the twin towers of the World Trade Center were attacked by Islamic militants in the United States. Predictably, when the London Underground transport system was attacked on 7 July 2005, these institutions once again came under the spotlight. While none of the perpetrators of 9/11 was a student of a Pakistani madrasa, one of the British terrorists had allegedly visited one. According to Maulana Sami al-Haq, head of his own faction of the Jamiat-i Ulama-i Islam and of the Dar al- Ulum Haqqaniyya in Akora Khattak (North West Frontier Province, or NWFP),‘linking the London bombing with Pakistani madrasas is only part of a broader campaign against these madrasas’ (Ali 2005).

But no matter what the Maulana says, the madrasas are widely seen as promoting Islamic militancy.

Recently (in March 2007) a madrasa for girls, the Jamia Hafsa of Islamabad, was in the news first for having occupied a children’s library to prevent the government from demolishing mosques built in green areas, and then for having kidnapped a woman who allegedly ran a brothel in Islamabad. Another major madrasa, the Jamia Binoriyya in SITE (Sindh Industrial Training Estate) (Karachi), has also been in the news – again for violence. On 23 June 2005, two of its clerics were gunned down by unidentified men. Later, ten students of this seminary were killed in a bomb blast. In short, the madrasas, which were earlier associated with conservatism, ossification and stagnation of Islam, are now seen as hotbeds of militancy in the name of Islam. After 9/11, a number of authors, both Western (Singer 2001) and Pakistani (Haqqani 2002), have connected the madrasas with militancy. At least three reports of the International Crisis Group (ICG) – published on 29 July 2002, on 20 March 2003 and on 16 January 2004 – have taken the nexus between militancy and the madrasas as a given. However, these reports do not take a simplistic view of militancy among Muslims and do point out that Pakistan’s military has strengthened the religious lobby in Pakistan, of which madrasas are a part, in its own political interests.

The madrasas are blamed for terrorism not only in Pakistan but in India as well (Winkelmann 2006). They are harassed by the police (Rahman 2005: 117–123) and by the Hindu right (Kandasamy 2005: 97–103). Thus, in India, as in Pakistan, the madrasas defend themselves against allegations of terrorism and remain deeply sceptical of bringing about changes which, they feel, would undermine their autonomy and the authority of the ulamawho

control them (Wasey 2005).

Review of literature

There was not much writing on the madrasas before the events of 9/11 in Pakistan. J.D. Kraan, writing for the Christian Study Centre, had provided a brief introduction (Kraan 1984). One of the first scholars to write on the madrasas was Jamal Malik. In his book (originally a doctoral dissertation), Colonialization of Islam, he included a chapter (V) on ‘The Islamic system of education’, which explained how the state dispensed alms (zakat) to the madrasas only if they complied with some of its rules and conditions. This had succeeded, ‘at least partially, in subordinating parts of the clergy and their centres to its own interests’ (Malik 1996: 153). However, during this process the clergy had succeeded, though again partially, in increasing its presence and voice in public institutions of learning. Later, A.H. Nayyar, an academic but not a scholar of Islam, had opined that sectarian violence was traceable to madrasa education (Nayyar 1998) – a position which was becoming the common perception of the intelligentsia of Pakistan at that time. The present writer wrote on language-teaching in the madrasas (Rahman 2002). The book also contained a survey of the opinions of madrasa students on Kashmir, the implementation of the sharia, equal rights for religious minorities and women, freedom of the media, democracy etc. (Rahman 2002: Appendix 14). By far the most insightful comment on the madrasa system of education and the world-view it produces comes from Khalid Ahmed, the highly erudite editor of the Daily Times English newspaper from Lahore. He claims that the madrasas create a rejectionist mind: one which rejects modernity and discourses from outside the madrasa (Ahmed, K.

2006: 45–67).

The ulama or the Islamists in Pakistan have been writing, generally in Urdu, in defence of the madrasas which the state sought to modernize and secularize.

Two recent books, a survey by the Institute of Policy Studies (patronized by the revivalist, Islamist, Jama’at-i Islami) on the madrasas (IPS 2002) and a longer book by Saleem Mansur Khalid (Khalid 2002), are useful because they contain much recent data. Otherwise the Pakistani ulama’s work is polemical and tendentious.

They feel themselves increasingly besieged by Western (Singer 2001) and Pakistani secular critics (Ahmad 2000: 191–192; Haqqani 2002) and feel that they should defend their position from the inside rather than wait for sympathetic outsiders to do it for them (as by Sikand 2001 and 2006). Reports on the increasing militancy with reference to Islam, especially its relationship with madrasas, have been produced by the ICG. The ICG proposes measures to reduce militancy in Pakistani society which include reforming the curriculum of these seminaries and having greater control over them (ICG 2007: 22).

Studies relating indirectly to Pakistan’s madrasas are also relevant for understanding them. An important book, comprising chapters by scholars on different aspects of madrasas in India, has been edited by Hartung and Reifeld (2006).

This book has an excellent historical section on the development of the madrasas in India and sections about these institutions in contemporary India. The focus of attention is on the changes (reforms?) which can be made in these institutions with a view to making them potentially peaceful and unthreatening. The seminal work on the ulama, and indirectly on the madrasas in which they are trained, is by Qasim Zaman (2002). This is an excellent study of how the traditional ulama can be differentiated from the Islamists who react to modernity by attempting to go back tofundamentalist,

and essentially political, interpretations of Islam.

This work draws for data on the chapter on madrasa education in my book entitled Denizens of Alien Worlds (2004: chapter 5, 77–98). While some of the information given there has been repeated here to provide the historical background, there is some new information and, more significantly, new insights provided by recent reading and the conference on Islamic education in South Asia in May 2005 at the University of Erfurt (Germany).

Type and number of madrasas

There is hardly any credible information on the unregistered madrasas. However, those which are registered are controlled by their own central organizations or boards, which determine the syllabi, collect a registration fee and an examination fee, and send examination papers, in Urdu and Arabic, to the madrasas where pupils sit for examinations and declare results. The names of the boards are as follows in Table 4.1.

At independence there were 245, or even fewer, madrasas (IPS 2002: 25). In April 2002, Dr Mahmood Ahmed Ghazi, the Minister of Religious Affairs, put the figure at 10,000 with 1.7 million students (ICG 2002: 2). They belong to the major sects of Islam, the Sunnis and the Shias. However, Pakistan being a

Table 4.1 Central boards of madrasas in Pakistan

predominantly

Sunni country, the Shia madrasas are very few. Among the Sunni ones there are three sub-sects: Deobandis, Barelwis and the Ahl-i Hadith (salafi).

Besides these, the revivalist Jama’at-i Islami also has its own madrasas.

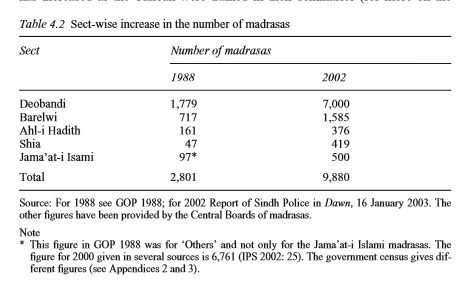

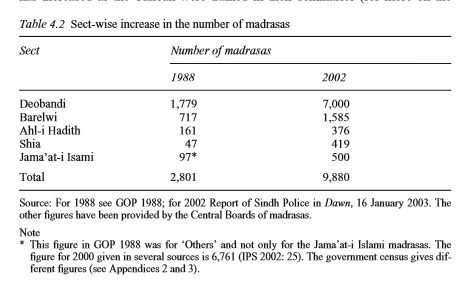

The number of madrasas increased during General Zia al-Haq’s rule (1977–1988), presumably because of the Afghan war and increased interest of the Pakistani state in supporting a certain kind of religious group to carry on a proxy war with India for Kashmir (more details about this will follow). The increase in the number of registered madrasas up to 2002 was as follows in Table 4.2.

The figures for 2005 given by the Ittehad Tanzimat Madaris-i Diniya (ITMD) on 23 September 2005 is some 13,000 seminaries (quoted from Ahmed 2006: 45). This is confirmed by the Ministry of Education which gives the figure of 12,979 madrasas in its National Education Census (GOP 2006: Table 8, p. 22).

P.W. Singer, however, gave the figure of 45,000 madrasas as early as 2000 but quotes no source for this number (Singer 2001). The enrolment figures of the government census are 1,549,242 students and 58,391 teachers for 2005 (GOP 2006: Table 9, p. 23). The enrolment in all institutions was 33,379,578 with a teaching staff of 1,356,802 according to the same source (ibid.: Table 3, p. 17).

The madrasas are not easy to count because, among other reasons, if a trust registered under the 1860 (Societies) Act or any other law ‘runs a chain of twenty madrasas, in government files it would be counted as one institution’ (ICG 2007: 5). Moreover, some seminaries, teaching only part of the madrasa curriculum, are registered as welfare or charity (ibid.:

5).

The Saudi Arabian organization, Haramain Islamic Foundation, is said to have helped the Ahl-i Hadith and made them powerful. Indeed, the Lashkar-i Tayyaba, an organization which has been active in fighting in Kashmir, belongs to the Ahl-i Hadith (Ahmed 2002: 10). In recent years, the Deobandi influence has increased as the Taliban were trained in their seminaries (for more on the

Table 4.2 Sect-wise increase in the number of madrasas

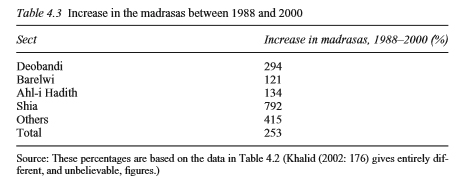

Table 4.3 Increase in the madrasas between 1988 and 2000

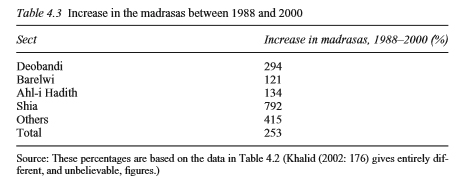

Taliban see Rashid 2000). This increase, calculated on the basis of figures available up to 2000, is as follows in Table 4.3.

It should be remembered that the Deobandi madrasas are concentrated in the NWFP and Balochistan which are ruled by the Muttahida Majlis-i Amal (MMA), a religious political party, which is seen as a threat to liberal democracy in Pakistan. Moreover, the people of the NWFP, being of the same ethnic group as the Taliban, are closely engaged in military action against the latter. This means that resentment against the government of Pakistan’s policy toward the Taliban, or al-Qaeda, are expressed in the idiom of Islam. This is a major source of anxiety as far as the Deobandi influence is concerned.

The sectarian divide among the madrasa

Islam, like Christianity and other major world religions, has several interpretations. The Sunni and the Shia sects made their appearance within less than a century of Islam’s emergence in Arabia (see Jafri 1979). But both these major sects have sub-sects or maslaks among them. The madrasas teach the basic principles of Islam as well as the maslak, the particular point of view of a certain subsect, to their students. For the Sunnis, the majority sect in Pakistan, the madrasas belong to the Deobandi, Barelwi or the Ahl-i Hadith maslak. Briefly, the Barelwis give a central place of extreme reverence to the Prophet of Islam to whom they attribute super-human qualities. They also believe in the intercession of saints (Sanyal 1996). The Deobandis deny the claims of the Barelwis, following a strict version of Islam in which saint worship is discouraged (Metcalf 1982). Being fundamentalists, the Ahl-i Hadith are evenmore strict

and, therefore, forbid the practices of folk Islam (Ahmed 1994). The Jama’at-i Islami is a revivalist religious party inspired by Abul Ala Maududi (1903–1979) which aims at taking political power so as to create an Islamic state and purify Islam (Nasr 1996). Besides the Sunni madrasas, there are Shia madrasas also, as we have seen.

All the madrasas, including the Shia ones, teach the Dars-i Nizami, though they do not use the same texts. They also teach their particular point of view (madhhab or maslak) which clarifies and rationalizes the beliefs of thesect (

Sunni or Shia) and sub-sect (Deobandi, Barelwi and Ahl-i Hadith). Moreover they train their students to refute what in their views are heretical beliefs and some Western ideas.

The curriculum of the madrasas

The Dars-i Nizami was evolved by Mulla Nizam al-Din Sihalvi (d.1748) at Farangi Mahall, a famous seminary of a family of Islamic ulama in Lucknow (Robinson 2002; for its contents see Sufi 1941 and Malik 1997: 522–529).

The Dars-i Nizami is taught for eight years. Students begin studying the Dars-i Nizami after they complete elementary school. Not all madrasas teach the full course. The ones which do are generally called jamia or dar al-ulum. The medium of instruction is generally Urdu, but in some parts of the NWFP it is Pashto, while in parts of rural Sindh it is Sindhi. However, the examinations of the central boards allow answers to be given only in Urdu and Arabic. Hence, on the whole, the madrasas promote the dissemination of Urdu in Pakistan.

All the madrasas teach some modified form of the Dars-i Nizami which comprises: Arabic grammar and literature; logic; rhetoric and mathematics among the rational sciences (ma’qulat), among the religious sciences are the principles of jurisprudence; the Qur’an and its commentaries; and the hadith. Some madrasas also teach medicine and astronomy. However, the books on these subjects – indeed on all subjects – are canonical texts sometimes going back to the tenth century. For instance, geometry is still taught through an Arabic rendition of Euclid (Aqladees). Medicine goes back to Abu Ali Ibn Sina (980–1037), whose Al-Qanun was written under the influence of the Greek theory of the imbalance of humours in the body creating disease. Similarly, the canonical texts on the Qur’an and the hadith are texts produced during the medieval period and do not have contemporary relevance.

Indeed, most people who write about the Dars-i Nizami complain that it is medieval, stagnant and, therefore, irrelevant to contemporary concerns. The typical criticism runs as follows:

Take, for instance, the case of the Sharh-i-Aqa’id, a treatise on theology (Kalam) written some eight hundred years ago, which continues to be taught in many Indian madrasas. It is written in an archaic style and is full of references to antiquated Greek philosophy that students today can hardly comprehend.

. . So, it asks question such as: Is there one sky or seven or nine?

Can the sky be broken into parts? Now all this has been convincingly refuted and consigned to the rubbish heap by modern science. (Mazhari 2005: 37–38)

Similarly the medieval commentaries (tafsir) on the Qur’an drew for arguments on the social and intellectual milieu of their period as did the law (fiqh) (Sikand 2005: 70–71). There are, of course, works in both Urdu and English on all these subjects (Maududi’s Tafhim al-Qur’an being an outstanding example of a contemporary commentary), but all of them would tend to expose the madrasa students to contemporary realities. And this exposure would make them question the hypocrisy and injustice of the Muslim elites of several countries – including Pakistan – who legitimize themselves in the name of Islam but exclude the ulama as well as the masses from the exercise of power and the enjoyment of its economic fruit. It would also make them question the hegemony of the West, and especially the United States, which allows the impoverishment of the Muslim masses in the name of globalization, market-oriented reforms and democracy. That this is happening is, of course, true. But it is not because of the medieval Dars-i Nizami. It is happening because of other influences and extracurricular reading material which shapes the world-view of madrasa students as well as other politically aware Muslims.

It is up to the person teaching the Qur’an or the hadith to give it whatever interpretation and time he decides and these vary according to the orientation of the teachers. However, the Dars-i Nizami, if anything, tends to disengage one from the modern world rather than engage with it. Moreover, the traditional orthodox ulama teach it in a way which is not amenable to contemporary political awareness. So, if the Dars-i Nizami does not create anti-Western, anti-elitist, sectarian militancy, what does?

One aspect of teaching in the madrasas which has received scant attention is that the students are taught the art of debate (munazara). This too is taught through the canonical texts: Sharifiyya of Mir Sharif Ali Jurjani (1413) and Rashidiyya of Abdul Rashid Jaunpuri (1672). However, the art is actually practised in such a way that madrasa students learn the skill of using rhetoric, polemic, intonation, quotation and arguments from their own sub-sect to win an argument. This kind of real-life debating is not taught in any secular institution in Pakistan where, indeed, the so-called ‘debates’ are written by teachers and memorized by the would-be debaters. The munazara is important because it is the bridge between memorization and the use of knowledge to present an argument relevant to present issues. It is also the bridge between the medieval contents of the curricula and the concerns of the contemporary world. The preachers in the mosques of Pakistan, graduates of madrasas (called maulvis or mullahs), use all the flourishes of rhetoric, the skills learnt for munazaras, in their sermons. These sermons, as anyone who has heard them will testify, have been becoming increasingly politicized. They dwell on the heresies in the Muslim world, the conspiracies of non-Muslims against the Muslims and, in recent years, the ongoing crusades in the lands of Islam – Palestine, Kashmir, Chechnya, Afghanistan,Iraq

and so on. These are all contemporary concerns and completely unrelated to the Dars-i Nizami. That is why it is not only the madrasa graduates but other Muslims too who have the maulvi’s political perspective. As the larger part of these sermons and the munazaras themselves consists of refuting other world-views, I will now focus upon the texts used for refutation among the Islamic-minded people (whether from the madrasa or not) in Pakistan.

The refutation of other sects and sub-sects

Refutation (Radd in Urdu) has always been part of religious education.

However, it is only in recent years that it has been blamed for the unprecedented increase in sectarian violence in Pakistan.

According to A.H. Nayyar, ‘The madrasahs have, not surprisingly, become a source of hate-filled propaganda against other Sects and the sectarian divide has become sharper and more violent’ (Nayyar 1998: 243). However, it appears that there was much more acrimonious theological debate among the Shias and Sunnis and among the Sunnis themselves during British rule than is common nowadays. The militancy in sectarian conflicts cannot be attributed to the teaching in the madrasas, though, of course, the awareness of divergent beliefs does create the potential for a negative bias against people of other beliefs.

They were also very bitter as the Deobandi–Barelwi munazaras of 1928 collected in Futuhat-i Nu’maniyya (Nu’mani n.d) illustrate. Moreover, the pioneers of the sects and sub-sects did indulge in refuting each other’s beliefs. For instance Ahmed Riza Khan, (1856–1921), the pioneer of the Barelwi school, wrote a series of fatwas (fatwa=religious decree) against Sir Sayyid of Aligarh, the Shias, the Ahl-i Hadith, the Deobandis and the Nadwat al-Ulama in 1896. These were published as Fatawa al-Haramain bi-Rajf Nadwat al-Main (1900) (Sanyal 1996: 203). The Barelwis, in turn, were refuted by their rivals. The followers of the main debaters sometimes exchanged invective and even came to blows but never turned to terrorism as witnessed in Pakistan’s recent history.

As the inculcation of sectarian bias is an offence, no madrasa teacher or administrator confesses to teach any text refuting the beliefs of other sects. Maulana Mohammad Hussain, Nazim-i Madrasa Jamia al-Salafiyya (Ahl-i Hadith) (Islamabad) said that comparative religion was taught in the final Alimiyya (M.A.) class and it did contain material refuting heretical beliefs. Moreover, Islam was confirmed as the only true religion, refuting other religions. The library did contain books refuting other sects and sub-sects but they were not prescribed in the syllabus. Maulana Muhammad Ishaq Zafar of the Jamia Rizwiyya Aiz al-Ulum (Barelwi) in Rawalpindi said that books against other sects were not taught. However, during the interpretation of texts the maslak was passed on to the student. Students of the final year, when questioned specifically about the teaching of the maslak, said that it was taught through questions and answers, interpretation of texts and sometimes some teachers recommended supplementary reading material specifically for the refutation of the doctrines of other sects and sub-sects.

In some cases, as in the Jamia Ashrafiyya, a famous Deobandi seminary of Lahore, an institution for publication, established in 1993, publishes only those articles and journals which are written by the scholars of the Deobandi school of thought (Hussain 1994: 42). Moreover, in writings, sermons and conversation, the teachers refer to the pioneers of their own maslak so that the views of the sub-sect are internalized and become the primary way of thinking.

However, despite all denials, the printed syllabi of the following sects do have books which refute the beliefs of other sects. The Report on the Religious Seminaries (GOP 1988) lists several books of Deobandi madrasas refuting Shia beliefs including Maulana Mohammad Qasim’s Hadiyyat al-Shia which has been reprinted several times and is still in print. There are also several books on the debates between the Barelwis and the Deobandis and even a book refuting Maududi’s views (GOP 1988: 73–74). The Barelwis have given only one book, Rashidiyya, under the heading of ‘preparation for debates on controversial issues’ (ibid.:

76). It is not true, however, that the students are mired in medieval scholasticism despite the texts prescribed for them. They do put their debates in the contemporary context though they refer to examples on the lines established by the medieval texts. The Ahl-i Hadith have given a choice of opting for any two of the following courses: the political system of Islam, the economic system of Islam, Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddimah,the

history of ideas and comparative religious systems. The Shia courses list no book on this subject.

Recently published courses list no book on the maslak for the Deobandis. The Barelwis mention ‘comparative religions’ but no specific text. The Ahl-i Hadith retain almost the same optional courses as before. The Shia madrasas list books on beliefs which include comparative religions in which, of course, Shia beliefs are taught as the only true ones. Polemical pamphlets claiming that there are conspiracies against the Shias are available. Incidentally such pamphlets, warning about alleged Shia deviations from the correct interpretations of the faith, are also in circulation among Sunni madrasas and religious organizations.

Moreover, some guidebooks forteachers

note that Qur’anic verses about controversial issues should be taught with great attention and students should memorize them. In one Barelwi book it is specified that teachers must make the students note down interpretations of the ulama of their sub-sect concerning beliefs and controversial issues so that students can use them later – i.e. as preachers and ulama.

The Jama’at-i Islami syllabus (2002) mentions additional books by Maulana Maududi and other intellectuals of the Jama’at on a number of subjects including the hadith. They also teach ‘comparative religions’.

The refutation of heretical beliefs

One of the aims of the madrasas, ever since 1057 when Nizam al-Mulk established the famous madrasa at Baghdad, was to counter heresies within the Islamic world and outside influences which could change or dilute Islam. Other religions are refuted in ‘comparative religions’ but there are specific books for heresies within the Islamic world. In Pakistan the ulama unite in refuting the beliefs of the Ahmadis (or Qaidianis) (for these views see Friedmann 1989). The Deoband course for the Aliyya (B.A.) degree includes five books refuting Ahmadi beliefs (GOP 1988: 71). The Barelwis prescribe no specific books.

However, the fatwas of the pioneer, Ahmad Riza Khan, are referred to and they refute the ideas of the other sects and sub-sects. The Ahl-i Hadith note that in ‘comparative religions’ they would refute the Ahmadi beliefs. The Shias too do not prescribe any specific books. The Jama’at-i Islami’s syllabus (2002) prescribes four books for the refutation of ‘Qaidiani religion’. Besides the Ahmadis, other beliefs deemed to be heretical are also refuted. All these books are written in a polemical style and are in Urdu which all madrasa students understand.

The refutation of alien philosophies

The earliest madrasas refuted Greek philosophy which was seen as an intellectual invasion of the Muslim ideological space. Since the rise of the West, madrasas, and even more thanthem

revivalist movements outside the madrasas, refute Western philosophies. Thus, there are books given in the reading lists for Aliyya (B.A.) of 1988 by the Deobandis refuting capitalism, socialism and feudalism. These books are no longer listed but they are in print and in the libraries of the madrasas. The Jama’at-i Islami probably goes to great lengths – judging from its 2002 syllabus – to make the students aware of Western domination, the exploitative potential of Western political and economic ideas and the disruptive influence of Western liberty and individualism on Muslim societies. Besides Maududi’s own books on all subjects relating to the modern world, a book on the conflict between Islam and Western ideas (Nadwi n.d.) is widely available.

These texts, which may be called Radd-texts, may not be formally taught in most of the madrasas as the ulama claim, but they are being printed which means they are in circulation. They are openly sold in the market and sometimes in front of mosques. They are also available in the libraries of madrasas. They may be given as supplementary reading material or used in the arguments by the teachers which are probably internalized by the students. In any case, being in Urdu rather than Arabic, such texts can be comprehended rather than merely memorized. As such, without formally being given the centrality which the Dars-i Nizami has, the opinions these texts disseminate – opinions against other sects, sub-sects, etc., seen as being heretical by the ulama, Western ideas – may be the major formative influence on the minds of madrasa students. Thus, while it is true that education in the madrasa produces religious, sectarian, sub-sectarian and anti-Western bias, it may not be true to assume that this bias automatically translates into militancy and violence of the type Pakistan has experienced. For that to happen other factors – the arming of religious young men to fight in Afghanistan and Kashmir; the state’s clampdown on free expression of political dissent during Zia al-Haq’s martial law; the appalling poverty of rural, peripheral areas and urban slums, Western domination and injustices etc. – must be taken into account.

Another factor which must be taken into account is Khalid Ahmed’s thesis that the madrasas create a rejectionsist world-view. In his own words:

The danger from madrasa is not its ability to train for terrorism and teach violence, but in its ability to isolate its pupils completely from society representing existential Islam and indoctrinate them with rejectionsim.

A graduate from a madrasa is more likely to be persuaded to activate himself in the achievement of an ‘exclusive’ shariah than a pupil drawn from a normal state-owned institution. (Ahmed 2006: 64)

Poverty and socio-economic class of madrasa students

Madrasas in Pakistan are generally financed by voluntary charity provided by the bazaar businessmen and others who believe that they are earning great merit by contributing to them. Some of them are also given financial assistance by foreign governments – the Saudi government is said to help the Ahl-i Hadith seminaries and the Iranian government the Shia ones – but there is no proof of this assistance. And even if it does exist, it goes only to a few madrasas, whereas the vast majority of them are run on charity (zakat=alms, khairat=charity, atiyat=gifts, etc.). The Zia al-Haq government (1977–1988) tried to gain influence on the madrasas by distributing the zakat funds to them in the 1980s. The only scholarly study of this is by Jamal Malik, who points out that most of the madrasas who received these funds were Deobandi. However, as the madrasas had to be registered, this increased the government’s influence over them (Malik 1996: 150–153).

The government of Pakistan gives financial assistance to the madrasas even now for modernizing textbooks, including secular subjects in the curricula and introducing computers. In 2001–2002 a total of Rs 1,654,000 was given to all madrasas which accepted this help. As the number of students is 1,065,277 this comes to Rs 1.55 per student per year. The government also launched a US$113 million plan to teach secular subjects to 8,000 willing madrasas according to the US Congressional Research Service report (New York Times, 15 March 2005.Quoted from Ahmed 2006: 47).

In November 2003, the government decided to allocate US$50 million annually to registered madrasas. However, not all madrasas accept financial help from the government and the money is not distributed evenly as the above calculations might suggest.

According to the Jamia Salafiyya of Faisalabad, the annual expenditure on the seminary, which has about 700 students, is 40,000,000 rupees. Another madrasa, this time a Barelwi one, gave roughly the same figure for the same number of students. This comes to Rs 5,714 per year (or Rs 476 per month) which is an incredibly small amount of money for education, books, board and lodging. In India, where conditions are similar to those in Pakistan, the madrasa Mazahir al-Ulum in Saharanpur (Uttar Pradesh), has 1,300 students and 115 employees and its income between 2000 and 2001 was Rs 9,720,649 or Rs 948 per student per year (Mehdi 2005: 93).

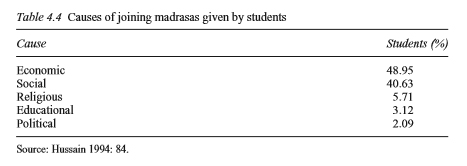

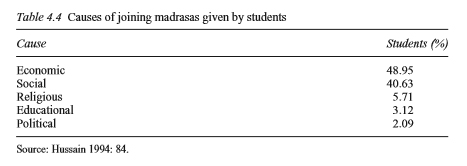

Table 4.4 Causes of joining madrasas given by students

The expenditure from the government in 2001–2002 was Rs 1,654,000 for all the madrasas in the country and as about 32.6 per cent of madrasas do not receive any financial support at all, the total spending on these institutions is very little (IPS 2002: 33). However, as mentioned above, there are plans to change this in a radical manner.

As the madrasas generally do not charge a tuition fee – though they do charge a small admission fee which does not exceed Rs 400 – they attract very poor students who would not receive any education otherwise. According to Fayyaz Hussain, a student who completed his ethnographic research on Jamia Ashrafiyya of Lahore in 1994, students joined the madrasa for the reasons listed in Table 4.4:

The categories have not been explained by the author nor is it known exactly what questions were asked from the students. According to Singer:

[the

] Dar-ul-Uloom Haqqania, one of the most popular and influential Madrasahs (it includes most of the Afghani Taliban leadership among its alumni) – has a student body of 1500 boarding students and 1000 day students, from 6 years old upwards. Each year over 15,000 applicants from poor families vie for its 400 open spaces. (Singer 2001)

According to a survey conducted by Mumtaz Ahmad in 1976:

more

than 80 per cent of the madrasa students in Peshawar, Multan, and Gujranwala were found to be sons of small or landless peasants, rural artisans, or village imams of the mosques. The remaining 20 per cent came from families of small shopkeepers and rural laborers. (quoted

from Ahmad 2000: 185)

According to a survey by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), 64 per cent of the madrasa students come from rural areas and belong to poor agrarian families (IPS 2002: 41). The present researcher also observed that many students, upon probing, confessed that their parents had admitted them in the madrasas because they could not afford to feed them and educate them in the government schools. Even such students, while making this confession, also insist that they are in the madrasas because of their love for Islam.

In my survey of December 2002 and January 2003, madrasa students and teachers were asked about their income. Not many replied to these questions, but of those who did 76.62 per cent suggest that they belong to poor sections of society. Many teachers of the madrasas (61.11 per cent) also belong to the same socio-economic class as their students (for details see Rahman 2004: Annex 1). The madrasas provide sustenance for all these poor people.

In short, the madrasas are performing the role of the welfare state in the country. This being so, their influence on rural people and the poorer sections of the urban proletariat will continue to increase as poverty increases.

Poverty and the roots of religious violence

The proposition that there is a connection between poverty and religious violence has empirical backing. Khalid Ahmed quotes the cases of Jihadi leaders from Pakistan who had a madrasa background. He says that, because they reject all forms of governance after the pious caliphate, they are in a condition of perpetual revolt against the modern state. He mentions a number of cases: Qari Saifullah Akhtar (b. 1958) (head of Harkat-i Jihad-i Islami who influenced the Islamist officers implicated in a coup in 1995); Maulana Masood Azhar (head of Jaish-i Muhammad); Abdullah Mehsud (from Banuri Masjid in Karachi; he abducted two Chinese engineers in 2004); Mufti Shamsuddin Shamazai (d. 2004) (patron of Harkat al-Mujahidin which has been known for fighting in Kashmir) (Ahmed 2006: 51–63). Qasim Zaman also tells us that in Jhang – the birthplace of the militant Sunni organization called the Sipah-i Sahaba – the proportion of Shias in the affluent urban middle class is higher than other areas of Pakistan. Moreover, the feudal gentry toohas

many Shia families. Thus the Sipah-i Sahaba appeals to the interests of the ordinary people who are oppressed by the rich and the influential. Indeed, Maulana Haqq Nawaz, the fiery preacher who raised much animosity against the Shias, was ‘himself a man of humble origin’ and ‘had a reputation for being much concerned with the welfare of the poor and the helpless, and he was known to regularly spend time at government courts helping out poor illiterate litigants’ (Zaman 2002: 125).

Another leader of the Sipah-i Sahaba, Maulana Isar al-Qasimi (1964–1991), also preached in Jhang. He too denounced the Shia magnates of the area, and the peasants, terrorized by the feudal magnates, responded to him as if he were a messiah. Even shopkeepers rejoiced in the aggressive Sunni identity he helped create. When the Shia feudal lords attacked and burnt some defiant Sunni shops this identity was further radicalized (Zaman 2002: 127). Masood Azhar, devoted to Haq Nawaz Jhangvi, became an aggressive fighter against the Shia as well as in Kashmir (Ahmed 2006: 61).

In the same manner, the Muslim radicals in the Philippines also attack social and economic privilege. Indeed, Islamist movements from Turkey to Indonesia talk of the poor and oppressed and sometimes do take up their cause. This has won them votes in Turkey where they have been suppressed by the secular military. It was also a major factor for mobilization in Iran against the Shah who was seen as being rich, wasteful, corrupt and decadent. So, though difficult to demonstrate, Islamic militancy – whether by radicalized madrasa students or members of Islamist or Jihadi groups in Pakistan – has an element of class conflict. It is, at least in part, a reaction of the have-notes against the haves. This is a dangerous trend for the country because madrasa students are taught to be intolerant of religious minorities and are hawkish about Kashmir. As they are also from poor backgrounds they express their sense of being cheated by society in the idiom of religion. This gives them the self-righteousness to fight against the oppressive and unjust system in the name of Islam.

The world-view of madrasa students

The madrasa students are the most intolerant of all the other student groups in Pakistan. They are also the most supportive of an aggressive foreign policy. In my survey of 2002–2003, mentioned earlier, the madrasa students were the only group of students – out of Urdu and English-medium school students – who supported both overt and covert conflict with India over Kashmir in large numbers. They were also against giving equal rights to non-Muslims (equal to Muslims) and women (equal to men) as citizens. These figures and the survey itself are given in Rahman 2004: Annex 2. However, an excerpt from the survey showing the key points can be found in Appendix 1.

Madrasas and militancy

The madrasas are obviously institutions which have a blueprint of society in mind. What needs explanation is that the madrasas, which were basically conservative institutions before the Afghan–Soviet War of the 1980s, are both ideologically activist and sometimes militant. This, indeed, is the major change which seems to have occurred in the Pakistani religious establishment. The British conquest was opposed with some armed resistance, but mostly the ulama retreated into their madrasas where orthodoxy, conserving the legacy of the past, was the order of the day. Folk Islam in South Asia was mystical, ritualistic and superstitious. The Barelwi sub-sect, which was very popular, supported extreme reverence for saints and rituals – such as the distribution of sweetmeats (halwa) on certain sacred days. This type of Islam was challenged by the Deobandis, the Ahl-i Hadith and the Jama’at-i Islami because none of these believed in the intercession of saints, the distribution of food on fixed days or other practices of folk Islam. These strict religious groups found unexpected allies among modernist Muslims and Westernized or secular urban people who were in a Muslim culture but whose world-view was Western. All these people opposed mysticism and folk Islam also, which they considered irrational and retrogressive. The result of these tendencies was that Islam came to be defined more and more in legalistic terms and the conservative point of view came to be replaced slowly by the revivalist one.

As the Pakistani ulama came to be drawn more and more into the ideology of the state (by becoming teachers of Arabic in ordinary schools or minor bureaucrats, for instance (see Malik 1996: 273)), they became politicized. They began to consider how they could pursue power to make the society Islamic, as they understood the term. The Iranian revolution of 1979, the defeat of the Soviet Union in Afghanistan in the late 1980s and, later, the rise of the Taliban convinced the Pakistani ulama that Islam could be a power in its own right. In short, the ulama were drifting from conservatism to revivalism and activism. The Deobandi and Ahl-i Hadith ulama were more consciously revivalist, as were the Shia ulama but, on the whole, the character of Islam, as preached in Pakistan, has undergone a tremendous change. Even the Barelwi sub-sect, with the second-largest madrasa board in the country, is not entirely peaceful. The ICG report of 2007 says that the ‘Faizan-e-Madina chain’ of madrasas is ‘certainly militant in its approach’, but adds that much of their hostility is directed ‘more towards the Deobandis and Ahl-e-Hadith than Shias’ (ICG 2007: 11).

So, while the basic texts of the Dars-i Nizami remain the same, what has changed is that the ulama are more conscious of world affairs which they see and describe with reference to the Crusades. Indeed, Karen Armstrong, writing on the impact of the Crusades on the world, states clearly that ‘The wars in the Middle East today are becoming more like the Crusades in this respect, especially in the religious escalation on both sides of the conflict’ (Armstrong 1988: 530). And it is not just the Israel–Arab conflict but other wars in the Muslim world which are seen in religious terms. Thus, even before Huntington presented his thesis about the ‘clash of civilizations’, the imams of Pakistani mosques used to describe world affairs with reference to such a theory. This political conciseness invoking the name of Kashmir and Palestine inPakistan,

has permeated much of the religious establishment and the middle class in Pakistan (see my survey of 1999 in Rahman 2002: Appendix 14). Thus, not just the madrasa teachers and students but people from secular institutions belonging to the lower-middle and middle classes respond to political Islam. Such people see the West in general and the United States in particular as the major forces for oppression and injustice in the world. According to Peter L. Bergen, author of a book on Osama bin Laden and his al-Qaeda group: ‘nowhere is bin Laden more popular than in Pakistan’s madrasas, religious schools from which the Taliban draw many of its recruits’ (Bergen 2001: 150). While it is not clear how Bergen obtained this information, my own impression is that his statement is largely accurate, but it can be said that bin Laden is also popular among a number of non-madrasa-educated young Muslims, especially the politically aware ones.

What made the madrasas militant?

Not all madrasas are militant. Those which are became militant when they were used by the Pakistani state to fight in Afghanistan during the Soviet occupation and then in Kashmir so as to force India to leave the state. Pakistan’s claim on Kashmir, as discussed by many including Alastair Lamb (1977), has led to conflict with India and the Islamic militants or jihadis, who have entered the fray since 1989. The United States indirectly (and sometimes directly) helped in creating militancy among the clergy. For instance, special textbooks in Darri (Afghan Persian) and Pashto were written at the University of Nebraska–Omaha with a USAID grant in the 1980s (Stephens and Ottaway 2002: Sec.A, p. 1).

American arms and money flowed to Afghanistan through Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence as several books have indicated (see Cooley 1999). At that time all this was done with the aim of defeating the Soviet Union.

The fact that until January 2002, when General Pervez Musharraf clamped down on Islamic militants, lists published by fighting groups included madrasa and non-madrasa students, suggests that at least some madrasas did send their students to fight in Kashmir. This has been reduced considerably, though The Herald, one of the most prestigious monthly publications from Karachi, tells us in its July 2005 issue that ‘hundreds of young boys between the ages of 13 and 15 years make ready cannon fodder for violent militant campaigns’ (p. 53). These young boys, who do not necessarily belong to madrasas, belong to private armies – there are said to be 15 of them – raised by different religious-political parties. The Herald’s implication is that, at some covert level, the state is still supporting these militant outfits so that they can be used to fight in Kashmir if the peace process fails.

However, while Pakistan’s military kept using militant Islamists in Kashmir, the United States was much alarmed by them – and not without reason, as the events of 9/11 demonstrated later. The Americans then attempted to understand the madrasas better. P.W. Singer, an analyst in the Brookings Institute, wrote that there were 10–15 per cent of ‘radical’ madrasas which teach anti-American rhetoric, terrorism and even impart military training (Singer 2001). No proof for these claims was offered. However, fighters from Afghanistan, Kashmir and even Chechnya did come to the madrasas, and it is possible that their contact with the students inspired the madrasa students to fight against those whom they saw as the enemies of Islam.

More significantly, the private armed groups or armies either associated with religious parties or acting on their own, train both madrasa and other school dropouts. They were financed by the intelligence agencies of Pakistan, as The Herald, Newsline, Friday Times and a number of Pakistani publications have repeatedly claimed in the past few years. Some of these armies such as Lashkar-i Tayyaba, Jaish-i Muhammad and Harkat al-Mujahidin print militant literature which circulates among the madrasas and other institutions. According to chapter 3 of a book entitled Ideas on Democracy, Freedom and Peace in Text- books (2003), Al-Da’wah uses textbooks for English in which many questions and answers refer to war, weapons, blood and victory.According to the author: ‘The students studying in jihadi schools are totally brain washed right from the very beginning.

The textbooks have been authored to provide only onedimensional worldview and restrict the independent thought process of children’ (Liberal Forum 2003: 72). Although these parties have been banned, their members are said to be dispersed all over Pakistan, especially in the madrasas. The madrasas, then, may be the potential centres of Islamic militancy in Pakistan not because of what they teach but because of the politically motivated people, committed to radical, political Islam, who seek refuge in them. However, such people are to be found outside the madrasas also. It is to this aspect that we turn now.

Militancy and Islamist fighters

Islamic militancy is going on in many parts of the world, notable among which are Palestine, Chechnya, the Philippines, Afghanistan, Kashmir and parts of Central Asia (for this last see Rashid 2002). However, what is surprising to many people is that secular institutions and Western countries also produce Islamic militants. As Olivier Roy points out, most young Islamist militants are trained in secular institutions. He cites many names of the 9/11 militants concluding that: ‘None (except for the Saudis) was educated in a Muslim religious school and Jarrah even attended a Lebanese Christian School. Most of them studied technology, computing, or town planning, as the World Trade Center pilots had done’ (Roy 2004: 310). Peter Bergen and Swati Pandey claimed that they ‘examined the educational backgrounds of 75 terrorists behind some of the most significant recent terrorist attacks against Westerners. They found that a majority of them were college-educated, often in technical subjects like engineering.’ About 53 per cent of the terrorists had been to college while ‘only 52 per cent of Americans had been to college’ (New York Times, 15 March 2005). This also seems to be true about the young British Muslims who struck on 7 July 2005 as well as the cadres of the Jama’at-i Islami in Pakistan who support fighting in Kashmir, though most of them come from the state education system and not the madrasas. Moreover, Sohail Abbas, a psychologist who interviewed jihadis who were incarcerated in Pakistani jails after having been captured in Afghanistan, where they had gone to fight the United States in defence of the Taliban in 2001, corroborates the same finding:

What we can say is that 232 jihadis out of the 319 in the Haripur group had attended school for at least five years or more. That means that most of the jihadis were in fact educated and that too in the mainstream education system. (Abbas 2006: 84)

In the Haripur group only 22.3 per cent had attended the madrasa while in the Peshawar group, out of 198, only 70 (35.5 per cent) had been to the madrasa. But even in the latter case, most (61.2 per cent) had attended the madrasa only for one to three months (Abbas 2006: 90–91). In short, mainstream education is no guarantee of preventing a person joining militant groups. In this context the influence of Islamists, whether in the peer group, family or teachers, is crucial.

Roy further points out that deterritorialized Muslims in Western countries, being overwhelmed by the dominant culture around them, fall back upon the Islamic identity. They are not guided by traditional texts or the ulama; they find their own meanings from the fundamental texts of the faith (the Qur’an and the hadith). Their neo-colonial reaction to the injustice of the world order, the irresistible globalization which seems to inundate all civilizations under the banner of Mickey Mouse, is to lash out in fury against Western targets and the elites in Muslim countries which support Western policies. They use the idiom of Islam but the anger which motivates them comes from a sense of being cheated. There are, of course, pegs to hang this anger on: Palestine, Chechnya, Kashmir, Afghanistan, Iraq,Iran

– the list can go on. But essentially, Muslim militancy is a reaction to Western injustice, violence and a history of exploitation and domination over Muslims. This can only be reversed by genuinely reversing Western militant policies and establishing a more equitable distribution of global wealth.

Can Islamic militancy be reduced?

In Pakistan, General Pervez Musharraf feels that Islamic militancy can be reduced as far as Pakistan’s madrasas are concerned, if secular subjects are taught in them and if foreigners are not allowed to study there.

What are called secular subjectswere

taught as ma’qulat in Mughal madrasas because one of the functions of these institutions was to produce bureaucrats for the state. What is now being advocated is to add the social sciences, English, computer skills and mathematics to thecurricula.

General Musharraf’s military government introduced a law called the Pakistan Madrasa Education (Establishment and Affiliation of Model Dini Madaris) Board Ordinance 2001 on 18 August 2001. According to the Education Sector Reforms (GOP 2002c) three model institutions were established: one each at Karachi, Sukkur and Islamabad. Their curriculum ‘includes subjects of English, Mathematics, Computer Science, Economics, Political Science, Law and Pakistan Studies’ for its different levels (GOP 2002c: 23). These institutions were not welcomed by the ulama (for opposition from the ulama see Wafaq al-Madaris No. 6: Vol. 2, 2001).

However, some modern subjects have been taught for quite some time in the madrasas. The Ahl-i Hadith madrasas have been teaching Pakistan studies, English, mathematics and general science for a long time (GOP 1988: 85). The Jama’at-i Islami also teaches secular subjects. The larger Deobandi, Barelwi and Shia madrasas have also made arrangements for teaching secular subjects including basic computer skills. According to a report in the weekly The Friday Times the Deobandi Wafaq al-Madaris has decided to accommodate modern subjects on a larger scale than ever before. They would make the students stay at school another two years to give a more thorough grounding in the secular subjects.The Wafaq has also formed committees to devise ways to capitalize on the government’s US$255 million for the madrasa reform scheme (Mansoor 2003). However, at present, the teaching is carried out by teachers approved by the ulama, or some of the ulama themselves. Thus, the potential for secularization of the subjects, which is small in any case, is reduced to nothing.

I believe that all attempts at secularizing madrasas will probably backfire. First, the madrasas work on charitable donations so they will not submit to the government’s fiat. Second, they are not the only source of militants. It is poverty and the fighting in Kashmir and elsewhere in the world which doesso,

therefore these external conditions – greatly dependent on government policy as they are – must be changed to produce peaceful people. Third, the textbooks of the socalled ‘secular’ subjects produced by the educational boards in Pakistan are anti- India and tend to glorify armed conflict (Aziz 1993; Saigol 1995; Rahman 2002: 515–524; and Nayyar and Salim 2003). Moreover, the people who will teach ‘secular’ subjects will be selected by the clergy and will likely be highly politicized Islamists who are evenmore fiery

in their denunciations of peace, liberal values and the West than even the ulama themselves. In any case, as we have observed earlier, Islamists from traditional educational institutions are even more prone to political violence than madrasa students. Thus, no amount of ‘secularization’ of the madrasas will eliminate violence.

The otherproposal, that

of not allowing foreigners to study in the madrasas, may be more successful. A law has now been introduced to control the entry of foreigners in the madrasas and keep a check on them. This law – Voluntary Registration and Regulation Ordinance 2002 – has, however, been rejected by most of the madrasas which want no state interference in their affairs (see Wafaq al-Madaris Vol. 3, No. 9, 2002, and unstructured interviews of the ulama). Indeed, according to Singer, ‘4,350, about one tenth, agreed to be registered and the rest simply ignored the statute’ (Singer 2001). The number of those who did not register is not known. However, on 29 July 2005 President Musharraf said in an interview with foreign correspondents that 1,400 foreign students would be expelled and visas to aspiring students denied (The News, 30 July 2005). If this policy is rigorously enforced, motivated extremists from other parts of the Muslim world may cease entering Pakistan. Certain other recommendations, for instance those coming from the ICG, need to be carefully studied for possible implementation (see ICG 2007: 11–12). For instance, the state must impose law and order without fear of political fallout. In the case of the 29 March kidnapping of women by Jamia Hafsa students in Islamabad the state failed to act, on the basis that the kidnappers were women. This kind of dereliction of responsibility cannot but encourage the Islamic militants to take the law into their own hands and increase what has been described as ‘Talibanization’ of the country.

Conclusion

Madrasas are not the only cause of potential violence in Pakistan or the world in general. They always had a sectarian bias as well as a bias against non-Muslims, but this did not necessarily translate into militancy. Nor are the madrasa students the only ones who are militant. Indeed, most of those who indulge in suicide bombings and actual fighting against non-Muslim targets are young, radical, angry Muslims who are dropouts or graduates of secular institutions of learning.

The madrasa students of Pakistan were radicalized because the United States and then successive governments in Pakistan used them to fight proxy wars against the Soviet Union and India (for Kashmir) respectively. Other Muslims were radicalized because of the neo-colonial policies of the West which makes Muslims feel they are being unjustly treated.

Thus, if militancy is to be decreased in Pakistan the ruling elite of the country would have to distribute wealth more equitably and provide justice to the poorest who send their children to the madrasas or religious armies. It would also have to eliminate all policies leading to the arming or militarization of religious cadres. This can only happen when there is peace with India, which is necessary if the world is to be at peace. Moreover, the government of Pakistan must oppose American aggression in the Muslim world without, however, allowing the Islamic militant groups to ignore the writ of the state as is happening in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) (the case of the kidnapping and murder of a school principal who had prevented the jihadis from recruiting boys from his school in March 2007). The use of religion to legitimize the rule of the elite, as has been happening so far, will also have to stop. This would mean the reversal of laws enacted during Zia al-Haq’s rule which are misused and give more power to the religious lobby. It also entails the rewriting of textbooks so that they promote tolerance, peace and human rights in the country. Above all, the state must establish the rule of law and economicjustice,

because without them the anger that has built up in the society can take the form of a religious struggle to protest against the degradation and violation of daily life.

Appendix 4.1

Survey 2003

Survey of schools and madrasas

This survey is given in full in Rahman (2004: Annexures 1 and 2). The gist of the responses to some of the crucial questions on opinions of students is given below:

What should be Pakistan’s priorities?

1. Take Kashmir away from India by an open war?

(1) Yes (2) No (3) Don’t know 2. Take Kashmir away from India by supporting Jihadi groups to fight with the Indian army?

(1) Yes (2) No (3) Don’t know 3. Support Kashmir cause through peaceful means only (i.e. no open war or sending Jihadi groups across the line of control)?

(1) Yes (2) No (3) Don’t know 4. Give equal rights to Ahmadis in all jobs etc.?

(1) Yes (2) No (3) Don’t know 5. Give equal rights to Pakistani Hindus in all jobs etc.?

(1) Yes (2) No (3) Don’t know 6. Give equal rights to Pakistani Christians in all jobs etc.?

(1) Yes (2) No (3) Don’t know 7. Give equal rights to men and women as in Western countries?

(1) Yes (2) No (3) Don’t know 82

Table 4.5 Consolidated data of opinions indicating militancy and tolerance among three types of school students in Pakistan in survey 2003 (%)

Appendi 4.2 and 4.3

Table 4.6 Number of Dini Madrasas by enrolment and teaching staff

And

Appendix 4.3

Table 4.7 Dini Madrasas by type of affiliation and area

Note

0%

0%

Author: Jamal Malik

Author: Jamal Malik