A Glossary of Shiite Methodology of Jurisprudence (Uşūl al-Fiqh)

0%

0%

Author: Alireza Hodaee

Author: Alireza Hodaee

Publisher: MIRI Press

Category: Jurisprudence Principles Bodies

ISBN: 978-9-641959-47-2

Author: Alireza Hodaee

Publisher: MIRI Press

Category: ISBN: 978-9-641959-47-2

visits: 7654

Download: 3659

Comments:

- PREFACE

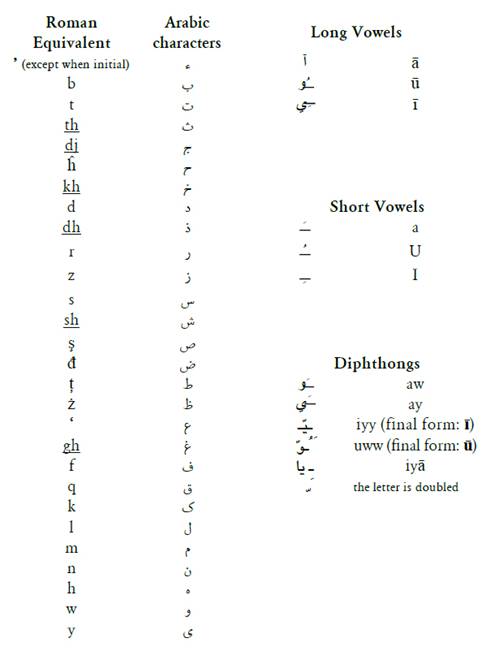

- Transliteration of Arabic Characters

- A

- • ‘Adam Şiĥĥat al-Salb (Incorrectness of Divesting)

- • al-Amāra (Authorized Conjectural Proof)

- • al-‘Āmm (General)

- • al-Amr (Command)

- • al-Aqall wa’l-Akthar al-Irtibāţiyyain (Relational Least and Most)

- • al-Aqall wa’l-Akthar al-Istiqlāliyyain (Independing Least and Most)

- • Aşāla al-Barā’a (Principle of Clearance)

- • Aşāla al-Ĥaqīqa (Principle of Literalness)

- • Aşāla al-Iĥtiyāţ or Ishtighāl (Principle of Precaution or Liability)

- • Aşāla al-Istişĥāb (Principle of Continuity of the Previous State)

- Constituents of Istişĥāb

- • Aşāla al-Iţlāq (Principle of Absoluteness)

- • Aşāla al-Takhyīr (Principle of Option)

- • Aşāla al-‘Umūm (Principle of Generality)

- • Aşāla al-Żuhūr (Principality of the Appearance)

- B

- • al-Barā’a al-‘Aqliyya (Intellectual Clearance)

- • al-Barā’a al-Shar‘iyya (Religious Clearance)

- • Binā’ al-‘Uqalā’ (Conduct of the Wise)

- D

- • Dalāla al-Iqtiđā’ (Denotation of Necessitation)

- • Dalāla al-Ishāra (Denotation of Implicit Conveyance)

- • al-Dalāla al-Siyāqiyya (Contextual Denotation)

- • Dalāla al-Tanbīh (Denotation of Hint)

- • Dalīl al-Insidād (Closure Proof)

- • al-Dawām (Permanence)

- • al-Đidd al-‘Āmm (General Opposite)

- • al-Đidd al-Khāşş (Particular Opposite)

- • al-Djam‘ al-‘Urfī (Customary Gathering)

- F

- • al-Fawr (Promptitude)

- G

- • Ghayr al-Mustaqillāt al-‘Aqliyya (Dependent Intellectual Proofs)

- H

- • Ĥadīth al-Raf‘ (Removal)

- • al-Ĥaqīqa al-Mutasharri‘iyya (Muslims' Literal Meaning)

- • al-Ĥaqīqa al-Shar‘iyya (Juristic-Literal Meaning)

- • al-Ĥudjdja (Authoritative Proof)

- • al-Ĥukm al-Wāqi‘ī (Actual Precept)

- • al-Ĥukm al-Żāhirī (Apparent Precept)

- • al-Ĥukūma (Sovereignty)

- I

- • al-‘Ibādī (Act of Worship)

- • al-Idjmā‘ (Consensus)

- • Idjtimā‘ al-Amr wa’l Nahy (Conjunction of the Command and the Prohibition)

- • al-Idjzā’ (Replacement)

- • al-‘Ilm al-Idjmālī (Summary-fashioned Knowledge)

- • al-‘Ilm al-Tafşīlī (Detailed Knowledge)

- • al-Inĥilāl al-Ĥaqīqī (Actual Reduction)

- • al-Inĥilāl al-Ĥukmī (Quasi-Reduction)

- • al-Istişĥāb al-Kullī (Continuity of the Previous State of the Universal)

- • al-Iţlāq (Absoluteness)

- • al-Iţlāq al-Badalī (Substitutional Absoluteness)

- • Iţlāq al-Maqām (Absoluteness of the Position)

- • al-Iţlāq al-Shumūlī (Inclusive Absoluteness)

- K

- • Kaff al-Nafs (Continence)

- • al-Khabar al-Mutawātir (Massive Report)

- • Khabar al-Wāĥid (Single Report)

- • al-Khāşş (Particular)

- • al-Kitāb (The Book)

- M

- • Mabāĥith al-Alfāż (Discussions of Terms)

- • Mabāĥith al-Ĥudjdja (Discussions of the Authority)

- • Mabāĥith al-Mulāzamāt al-‘Aqliyya (Discussions of Intellectual Implications)

- • al-Mafhūm

- • Mafhūm al-‘Adad (Number)

- • Mafhūm al-Ghāya (Termination)

- • Mafhūm al-Ĥaşr (Exclusivity)

- • Mafhūm al-Laqab (Designation)

- • al-Mafhūm al-Mukhālif / Mafhūm al-Mukhālafa (Disaccording Mafhūm)

- • al-Mafhūm al-Muwāfiq / Mafhūm al-Muwāfaqa (Accordant Mafhūm)

- • Mafhūm al-Sharţ (Condition)

- • Mafhūm al-Waşf (Qualifier)

- • al-Marra (Once)

- • Mas’ala al-Đidd (Problem of the Opposite)

- • al-Mudjmal (Ambiguous)

- • al-Mukhālafa al-Qaţ‘iyya (Definite Opposition)

- • al-Mukhaşşis (Restrictor)

- • al-Mukhaşşis al-Munfaşil (Separate Restrictor)

- • al-Mukhaşşis al-Muttaşil (Joint Restrictor)

- • Muqaddimāt al-Ĥikma (Premises of Wisdom)

- • Muqaddima al-Wādjib (Preliminary of the Mandatory Act)

- • al-Muqayyad (Qualified)

- • al-Muradjdjiĥāt (Preferrers)

- • al-Mushtaqq (Derived)

- • al-Mustaqillāt al-‘Aqliyya (Independent Intellectual Proofs)

- • al-Muwāfaqa al-Qaţ‘iyya (Definite Obedience)

- N

- • al-Nahy (Prohibition)

- • al-Naskh (Abolishment)

- • al-Naşş (Explicit-Definite)

- Q

- • Qā‘ida Qubĥ ‘Iqāb bilā Bayān (Principle of Reprehensibility of Punishment without Depiction)

- • Qā‘ida al-Yaqīn (Rule of Certainty)

- • al-Qaţ‘ (Certitude, Knowledge)

- • al-Qiyās (Juristic Analogy)

- Definition of Qiyās

- Shiite Position on Qiyās

- S

- • al-Şaĥīĥ wa’l A‘amm (Sound and What Incorporates Both)

- • al-Shubha Ghair al-Maĥşūra (Large-Scale Dubiety)

- • al-Shubha al-Ĥukmiyya (Dubiety concerning the Precept)

- • al-Shubha al-Mafhūmiyya (Dubiety concerning the Concept)

- • al-Shubha al- Maĥşūra (Small-Scale Dubiety)

- • al-Shubha al-Mawđū‘iyya (Dubiety concerning the Object)

- • al-Shubha al-Mişdāqiyya (Dubiety concerning the Instance)

- • al-Shubha al-Taĥrīmiyya (Dubiety as to Unlawfulness)

- • al-Shubha al-Wudjūbiyya (Dubiety as to Obligation)

- • al-Shuhra (Celebrity)

- • al-Sīra (Custom)

- • Sīra al-Mutasharri‘a (Custom of People of the Religion)

- • al-Sunna

- T

- • al-Ta‘ādul wa’l Tarādjīĥ (Equilibrium and Preferences)

- • al-Ta‘āruđ (Contradiction)

- • al-Tabādur (Preceding)

- • Tadākhul al-Asbāb (Intervention of Causes)

- • Tadākhul al-Musabbabāt (Intervention of the Caused)

- • al-Takhaş şuş (Non-Inclusion)

- • al-Takhşīş (Restriction)

- • al-Taqrīr (Acknowledgment)

- • al-Ţarīq (Path)

- • al-Tazāĥum (Interference)

- U

- • al-‘Umūm al-Badalī (Substitutional Generality)

- • al-‘Umūm al-Istighrāqī (Encompassing Generality)

- • al-‘Umūm al-Madjmū‘ī (Total Generality)

- • al-Uşūl al-‘Amaliyya (Practical Principles)

- • Uşūl al-Fiqh

- • al-Uşūl al-Lafżiyya (Literal Principles)

- W

- • al-Wađ‘ (Convention)

- • al-Wađ‘ ‘Āmm wa’l Mawđū‘ lah ‘Āmm (Convention General and Object of Convention General)

- • al-Wađ‘ ‘Āmm wa’l Mawđū‘ lah Khāşş (Convention General and Object of Convention Particular)

- • al-Wađ Khāşş wa’l Mawđū‘ lah ‘Āmm (Convention Particular and Object of Convention General)

- • al-Wađ‘ Khāşş wa’l Mawđū‘ lah Khāşş (Convention Particular and Object of Convention Particular)

- • al-Wađ‘ al-Ta‘ayyunī (Convention by Determination)

- • al-Wađ‘ al-Ta‘yīnī (Convention by Specification)

- • al-Wađ‘ wa’l Mawđū‘ lah (Convention and Object of Convention)

- • al-Wādjib al-‘Aynī (Individual Mandatory Act)

- • al-Wādjib al-Kifā’ī (Collective Mandatory Act)

- • al-Wādjib al-Mashrūţ (Conditional Mandatory Act)

- • al-Wādjib al-Mu‘allaq (Suspended Mandatory Act)

- • al-Wādjib al-Muđayyaq (Constricted Mandatory Act)

- • al-Wādjib al-Munadjdjaz (Definite Mandatory Act)

- • al-Wādjib al-Muţlaq (Absolute Mandatory Act)

- • al-Wādjib al-Muwassa‘ (Extended Mandatory Act)

- • al-Wādjib al-Ta‘abbudī (Religiously Mandatory Act)

- • al-Wādjib al-Ta‘yīnī (Determinate Mandatory Act)

- • al-Wādjib al-Takhyīrī (Optional Mandatory Act)

- • al-Wādjib al-Tawaşşulī (Instrumental Mandatory Act)

- • al-Wurūd (Entry)

- Z

- • al-Żāhir (Apparent)

- • al-Żann al-Khāşş (Particular Conjecture)

- • al-Żann al-Muţlaq (Absolute Conjecture)

- Table of Technical Terms

- 1. English-Arabic

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- G

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- W

- 2. Arabic-English

- ا

- ب

- ت

- ج

- ح

- خ

- د

- ر

- س

- ش

- ص

- ض

- ط

- ظ

- ع

- غ

- ف

- ق

- ک

- ل

- م

- ن

- و

- ی

- Selected Bibliography