2- On the origins of the Iranian constitution: Muhammad Baqer as-Sadr’s 1979 treatises

Introduction: on wilayat al-faqih

There is little doubt that the theory of wilayat al-faqih, as developed in Khumaini’s lectures of Najaf, was most influential in the creation of the constitution passed in Iran in the wake of the Revolution. In these Najaf lectures, delivered in 1970, Khumaini developed the idea of the’ulama’s responsibility in the state, in the form of an institutionalised structure which should be entrusted with the country’s leadership.

The general thrust of the theory is not completely original. One can find the idea of the mujtahids’ responsibility in the state developed much earlier in the century, for example when a dispute over Parliament and the new State of Iraq broke out in 1922-3.

After the great revolt of Najaf against the British, which was led by the’ulama, the continuation of this leadership through some representation in the state could not fail to be advocated in circles close to the Shi’i jurists:

The program of the’Union of’Ulama’, which was received in Kadhimain on November 7, 1926, from Shaikh Jawad al-Jawahiri and was read at the house of the lalim Sayyid Muhammad as-Sadr on November 13,1926, called for the establishment of a more intimate link between the’ulama of Persia and Iraq; the formation of religious societies which would be charged with the welfare of Islam in general, and which would work in Persia and Iraq for the improvement of relations with Turkey and Soviet Russia; and lastly, the control of these societies by the mujtahids in their capacity as religious leaders of the people.

In other countries of the Arab and Muslim world, similar propositions for the protection of’the welfare of Islam in general’ by the ‘ulama were also voiced at critical junctures in the encounter with colonialism, either in a direct fashion, such as the Persian Constitution of 1906 after the 1905 popular upheaval, or indirectly, as in some of the debates in Egypt in the 1920s.

In contrast to the embryonic shape of this advocacy, Khumaini had gone to great length in the call for the’ulama to intervene directly in all matters political, and his Najaf lectures were primarily concerned with the legitimation of this necessity.’They [the enemies of Islam] said Islam was not concerned with the organisation of life and society, or institutions of any kind, but that it should only be concerned with rules of menstruation and parturition, and that there might be in Islam some ethical issues, beyond which it had no say on life or the ordering of society.’

Islamic Government is a long diatribe against this state of affairs, and the book of the Muslim mujtahid develops a theory of wilayat along two major lines:

(1) The involvement of the ‘ulama in the affairs of government: most arguments in the first chapter, and part of the second, are devoted to Khumaini’s insistence, based on the Qur’an and on Shi’i hadith, on the necessity for the’ulama to get involved in government:’ Teach [Khumaini is addressing his students in Najaf] people the truth of Islam, so that the young generation does not think that the people of learning are confined to the corners of Najaf and Qum, and that they separate religion from politics.’

A minimal involvement is not unusual in Shi’i modern history, and was manifest at major historical crossroads, most prominently in Iran during the Tobacco Revolt,

in the 1905 constitutional revolution,

and in the Iraq of the First World War, when the Iraqi South rebelled against the British invasion.

But this involvement can be portrayed as a negative one. It came when the society the ‘ulama knew and represented was facing what they perceived as a daunting threat. In the day-to-day development of the country, they had not actively and positively taken part in the life of government, until the theoretical lectures of Khumaini in Najaf, and the Iranian Revolution of 1978 in practice.

(2) The emphasis on the role of leadership for the ‘ulama in government:

it is one thing to advocate political intervention premised on the alleged fusion of din and dawla (religion and state) in Islam, another to call for the’ulama to assume total responsibility at the highest level of the state apparatus.

There is some ambiguity in Khumaini’s exact definition of leadership.

Leadership can be meant to cover a wide spectrum of measures, ranging from the lowest level, non-binding advice, to the highest level, which means effective executive and legislative power: passing legislation and implementing it through state coercion. Between these two extremes, the public responsibility entailed in the jurists’ leadership crosses several thresholds.

The most conspicuous manifestation is the equation of leadership and guidance which, translated constitutionally, means a form of overview of society that censures the consonance of civil servants in the state, citizens at large, and legislation, within a frame of overarching references generally embodied in the Constitution. This latter acceptation is common in modern democracies, even though it does not go under the name of’ leadership’. This is the case of the Conseil d’Etat and the Conseil Constitutionnel in France, the Supreme Court in the United States, and various similar judicial institutions in many countries in the world.

In Iran, this leadership was constituted by the body of jurists entrusted with supervising the respect for Islamic law in Article 2 of the Supplementary Laws of the 1906 Constitution.

Even though this council rarely met, it was at least an important precedent in the country’s constitutional tradition.

Where does Khumaini in velayat-efaqih put the responsibility (velayai) of the ‘ulama in this scale?

No clear answer emerges in the text of 1970, but the weight of the argument tends toward some combination between the guidance concept of 1906 and a more decided attitude towards governmental matters as they are understood in the executive-legislative mould of contemporary democracies. On the side of Khumaini’s advocacy of absolute control by the’ulama, are the diatribes against the importation of foreign laws, amongst which Khumaini cites the Belgian provisions which were at the heart of Persia’s 1906 constitutional text:’At the beginning of the constitutional movement, when people wanted to write laws and draw up a constitution, a copy of the Belgian legal code was borrowed from the Belgian embassy and a handful of individuals used it as the basis for the constitution they then wrote ...’

Also, Khumaini equates wilaya with’the governing of people, the administration of the state and the execution of the rules of law’.

But there are also passages acknowledging a relative power of the’ulama in terms of state control. This appears a contrario when Khumaini writes:’ If the sultans have some faith, they just need to issue their actions and decisions by way of the fuqaha, and in this case, the true rulers are thefuqaha, and the sultans become mere agents for them.’

This last passage echoes a well-known tradition in Iran, to the effect that a country is plagued when ‘ulama are found at the doorsteps of rulers, and blessed when the rulers are at the tulama’s doorstep.

That the’ulama have the final word does not alter the reality of an effective separation of powers. The supervisory function lies precisely in this nuance, and it is hard to find in Khumaini’s Najaf lectures an exact balance as to the role of the’ulama and the rulers in the state. The final word, certainly, is the’w/ama’s, but the substantial content of their sway remains undefined.

In 1970, Khumaini was more concerned with arguing against the quietist interpretation of the hadith and of the Shi’i tradition, and less with the details of the nature of the’ulama leadership. This is understandable in view of the declining role of the’ulama in society, even as a consultative body. In 1970, the 1906 Constitution, especially in the dimension specified by Article 2, was a dead letter.

When the ulama’ took over in 1979, a gap remained, and there is to date a missing link between the generalities of the Najaf lectures and the text of the Iranian Constitution.

Thus the arguments by Khumaini and in the Persian circles around him, constituted, in effect, broad suggestions for interventionism. The scheme adumbrated in the Najaf conferences and in Mahmud Taliqani’s constitutional articles

only offered a general framework, which lacked the necessary specification of institutional articulation. Another text may have exercised a more direct influence on the framing of Iran’s present constitution.

This treatise, written by Muhammad Baqer as-Sadr in 1979, was designed precisely in answer to a query by fellow Lebanese’ulama on Sadr’s view of a Project for a Constitution for Iran.

Before discussing the substance of this Note} and comparing it with the structures at work in the Iranian Constitution, there are two further, more abstract levels in the theory of the Islamic state. The first abstraction is ontological. It is based on the necessity of establishing the theory of the Islamic state, as closely as possible, on the Urtext (the Qur’an).

On which Qur’anic ground can the responsibility for this state, or its leadership by the ‘ulama be defended ? In other words, why should the jurist be entrusted with any such kind of responsibility in the affairs of the State ?

To the necessity of finding a textual basis in the Qur’an, the modern theoreticians among the ‘ulama have answered diversely. Often, it is the verse on the shura

which is put forward, but it is clearly a text that cannot be used to legitimise a leadership by the’ulama. Khumaini, in his Najaf lectures, also referred to the’amr bil-ma’ruf wan-nahi lan al-munkar’ (enjoining the good and forbidding the evil).

This reference is even less precise from a constitutional point of view, and cannot be construed to mean more than the necessity for the moral injunction to enter the public realm. However, the chapter on amr bil-malruf in the major compendium of laws of Khumaini includes some interesting details on his view of the attitude of the ‘ulama towards the state from a negative point of view: but this discussion is an extension of the Shi’i jurists’ classical texts.

The second level of abstraction in Islamic state theory is philosophical, and looks for the significance of power in an Islamic state from the perspective of its survival through fourteen centuries of adversity. In the tradition of Ja’farism, this dimension is coupled with Shi’ism as a minority sect in the world of Islam, and the importance of its tradition of resistance as exemplified in Karbala and the Husayn paradigm. But in the modern activist texts, as in Khumaini’s Hukuma Islamiyya, the philosophical dimension is of little concern. In Sadr’s attempt to complete his constitutional view in 1979, this philosophical aspect, which carries further the tradition of Falsafatuna

was the object of a pamphlet on The Sources of Power in the Islamic State.

Before turning to aspects of the constitutional question dealing with the substance of the power relationship and the ‘ulama’s responsibility in the state, it is important to see how a more sophisticated position has been developed by Muhammad Baqer as-Sadr through the grounding of such a power in the Qur’anic text, and how Sadr sought to expose a philosophical thread running through the whole of Islamic history.

Stage 1: reading the Qur’an constitutionally

It is in verse 44 of the fifth sura (chapter) of the Qur’an that Muhammad Baqer as-Sadr finds the legitimation of the Islamic state, and of the institutionalisation of the’ulama’s position in it. First published in 1979, Khilafat al-Insan wa Shahadat al-Anbiya’

provides a significant insight into the Iraqi scholar’s ideas and positions at the end of his life, and is one of the most sophisticated texts in the modern literature of Islam on the connection between the Qur’an and the structure of an Islamic state. This will appear more significantly in a comparative approach with some other key interpretations of verse 44 in the modern age.

Verse 44 is rendered thus in one modern translation:

It was We Who revealed

The Law (to Moses) [The Torah, at-tawrat]: therein

Was guidance and light

By its standard have been judged

The Jews, by the Prophet [Prophets, nabiyyun]

Who bowed (as in Islam)

To Allah’s Will, by the Rabbis [rabbaniyyun]

And the Doctors of Law [ahbar]:

For to them was entrusted

The protection of Allah’s Book

And they were witnesses [shuhada’, from shahada] thereto.

This verse could be read as a very narrow text, and this was done frequently in the past. Some of the authoritative modern tafsirs continue to read the verse narrowly, as will be suggested in this section. Such a narrow interpretation emphasises the received sabab an-nuzul (cause or occasion of revelation) associated with the verse. The case is of two Jews in a dispute over adultery. They came to the Prophet for arbitration, and the Prophet emphasised the relevance of their own law as it was revealed in the books and developed by the ahbar in charge of its interpretation.

The institutional incidence of the verse in this interpretation is obviously limited. Legally, it could be classified as a case of conflict of laws, with a relatively strict adjudicatory system.

In contrast, Sadr’s interpretation is characterised by a scheme that is tinged both by a constitutional-political exegesis and a characteristically Shi’i understanding. After citing the verse, Sadr explains:

The three categories in the light of this verse are the nabiyyun, the rabbaniyyun, and the ahbar. The ahbar are the’ulama of the shari’a, and the rabbaniyyun form an intermediate level between the nabi and the’alim, the level of the Imam.

It is therefore possible to say that the line of the shahada

(testimony) is represented by:

First -The Prophets (anbiya1).

Second -The Imams, who are considered a divine (rabbani) continuation of the Prophets in this line.

Third -The marja’iyya, which is considered the righteous (rashid) continuation of the Prophet and the Imam in the line of the shahada.

In this interpretation of the Qur’anic verse, Sadr extracts a purely Shi’i institutional scheme. First, he omits the patent Judaic reference by subsuming the Torah under a’ divine book’ classification. Then, by referring to the rabbaniyyun not as the rabbis, which the context would suggest, but as the twelve Imams of the Ja’faris, he gives a strong Shi’i ring to his interpretation. The ahbars, the Doctors of the Law in the translation, are understood to mean the Shi’i marjaiyyaa, which constitutes for Sadr the last body of witnesses in the line of the shahada, and which, in the verse cited, is entrusted to protect the Book after the Prophet Muhammad and the Twelve Imams. Thus charged with an implication of public responsibility, Sadr’s shahada confers on the marja’iyya the task of guarding the Islamic Republic in the fashion designed by Plato for the Philosopher-Kings of his ideal city.

The originality of this reading of the Qur’an appears more fully when contrasted with the leading tafsirs of the twentieth century.

Muhammad Rashid Rida, in his Tafsir al-Manar, understands the verse restrictively:’ The Prophets, Moses and the Prophets after him, rule over those who became Jews (hadu). [Moses and the Prophets of Israel rule over] the Jews in particular because it is a law specific to them, not a general law, and this is why the last one of them, Jesus, said: I was sent only for the lost sheep of Israel.’

Therefore, in the reading of this passage by Muhammad’Abduh’s disciple, the importance of the whole citation is curtailed because of the Judaic reference. In Rida’s tafsir, no constitutional system is mentioned which could even suggest that a religious leader, and less so a marja’ is destined to continue the line of shahada.

For Sayyid Qutb also, some fifty years later, the Shi’i dimension is understandably absent. However, the political appeal of the text is strongly emphasised, and the reading into it of the need for a fully Islamic political system is determinedly underlined:

This text, wrote the theoretician of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, addresses the most crucial (dangerous, akhtar) issue of the Muslim way (manhaj), the system of governance and life in Islam... In this sura, [this issue] takes a precise and assured form, that the text conveys in its wording and in its expressions, not just through its concepts and suggestions.

Qutb however does not dwell on the constitutional system alluded to, as Sadr does. The importance emphasised in connection with this verse resides in its general appeal for a total and undiluted Islamic society, in which the prescriptions of the Qur’an are adopted and respected in all fields of life.

Qutb uses this text, which is indeed the most explicit on the question of governance and the necessity to follow the Qur’an, to advocate a state which is completely Islamised, that is, in his world view, a state which goes, so to speak, by the Book. Furthermore, on the role of the ahbar (Sadr’s marja’iyya), Qutb takes a diametrically opposed stance to Sadr’s:

Nothing is uglier than the betrayal of those who have been entrusted,... and those who bear the name of’ religious men’ (rijal ad-din) betray, deform, and falsify, remain silent over what should be done to rule by what God has prescribed, and strip the word from its context to please the whims of those in power, to the detriment of the Book of God.

This text implies that there are two categories of religious men, those who betray, deform and falsify to serve the people in power, and the honest ones who presumably do not act’to the detriment of the Book of God’. For Qutb, who had completely been abandoned by the Egyptian’ulama, and not surprisingly in view of the coyness he perceived as the characteristic of the shaykhs of the Azhar, the worst thing would have been to entrust the rule of God to the religious hierarchy. Neither he, nor most of the historical leaders of the Brethren, such as Hasan al-Banna and’Umar Talmasani, had much political affinity with the quietist Azhar.

In contrast, Muhammad Baqer as-Sadr was evolving in Najaf among a whole generation of’religious men’, who by 1979 were looking for him to be the Khumaini of Iraq. Understandably, the reservation of Qutb towards an interpretation of the Qur’an which underlines the shahada of the’ulama in the definition of the Islamic state was not shared by the Iraqi mujtahids.

However, the emphasis on the political dimension of the verse, as well as on the foundation of a’nucleus’ of the Islamic state in the Qur’an renders Sadr and Qutb very close in parts of their tafsir of verse 44.

Sadr’s exegesis is also peculiar in the Shi’i world. But its variance with the great Shi’i interpreters has a logic of its own. Tabataba’i’s Mizan

and Shirazi’s Taqrib

both denote Shi’i references in the explanation of the sura.

For Shirazi, the verse means that the Torah as a divine book should be abided by, until superseded, by a Book of better guidance and greater light.

In so far as the text of the Holy Book has not been adulterated, it is permissible for those who believe in it to be ruled by it, and’Ali’s authority is invoked to substantiate this interpretation in reference to the Jews and the Christians.

Like Rida’s, Shirazi’s reading is restricted and non-political: he tends to limit the impact of the verse to the Judaic context. Even the Shi’i element remains general, despite the reference to the first Imam.

Not so Tabataba’i. His comment is more universal, in that like Qutb and Sadr, he reads into the text a more general statement than the reference to the Torah might suggest.

Unlike theirs, his universality is not political, and this political neutrality resembles Rida’s and Shirazi’s. But Tabataba’i introduces a notion absent from the other tafsirs, and this notion is expanded in Sadr’s scheme to form the key to his whole constitutional system.

Tabataba’i writes:’ It is certain that there is one level (manzila) between the levels of the anbiya’ and the ahbar, which is the level of the Imams and the combination of prophecy and Imamat in one group does not preclude them being separated in another.’

Thus a formal separation is introduced between the three categories, the Prophets, the Imams, and the’ulama:’And [‘Ali’s] saying: "the Imams are beneath iduna) the Prophets", means that they are one degree below the level of the Prophets according to the gradation of the verse, in the same way as the ahbar, who are the’ulama,

are beneath the Imams (rabbaniyyun).’

This exclusively Shi’i scheme,

it should be noted, is purely theological, and is included in the context of Tabataba’i’s’narrative analysis’ (bahth rizva’i).

It is not alluded to in the section’on the meaning of the shari’a’ devoted to the legal interpretation of this passage.

Unlike Sadr, Tabataba’i does not derive a constitutional system from verse 44, and this restriction is in accordance with his general appreciation of the Shi’i scholars’ social role to be more a spiritual than a political guidance.

But only Tabataba’i’s categories, and the similar Shi’i tradition of tajsir,

indicate how the celestial vault of Sadr’s constitutional scheme was formed.

This Shi’i classification, which endows Sadr’s marja’iyya with the function of continuing the public role of the Prophets and the Twelve Imams, ushers in an’ideological leadership’, as Sadr calls it, which is meant to offer’the objective criterion to the community from the point of view of Islam... not only as to the fixed elements of legislation in the Islamic society, but also to the changing temporal elements. [The marja’] is the supreme representative of the Islamic ideology.’

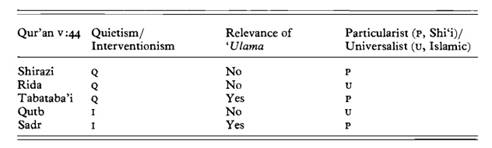

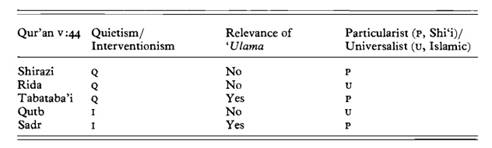

Several positions emerge in the interpretation of verse 44 of the Qur’an.

They are summarised in the following table:

For Sadr and Qutb, this verse should be interpreted as an invitation to a determined political intervention based on the necessary application of Qur’anic rules, qua shari’a, in society. But Qutb, unlike Sadr, sees no overall Shi’i scheme and keeps the religious hierarchy out of the role of leadership in the city, if indeed he trusts it with any role at all. In contrast, Tabataba’i, like Sadr, considers the role of the’ulama to be essential in the reading of the verse. This explains also that they are both particularist in their interpretation.

The ‘ulama are perceived as the followers of the Prophets and of the Shi’i Imams.

It is interesting to note that the Shi’i Shirazi is also a particularist, but his emphasis on Shi’ism does not come from any relevance he accords the’ulama in the reading of the verse. There is no mention of any succession of the Imams which would, as with Tabataba’i and Sadr, devolve on the’ulama.

His Shi’ism is merely’cultural’. In comparison, the reading of the Sunni Qutb and Rida, as would be expected, carries no trace of Shi’ism, and their interpretation becomes ipso facto universalist: their reference is to an Islam in which particularist (communitarian) beliefs are irrelevant.

Sadr and Qutb are the only interpreters who assign a political value to the verse. Shirazi, Rida and Tabataba’i read it’apolitically’. For Shirazi, Tabataba’i and the Rida of the Manar

the verse carries no political charge.

Shirazi and Rida’s readings are restricted to an interpretation that limits the impact of the verse, and confines it to its Jewish context. The sabab an-nuzul becomes for them the only horizon of its application. Albeit not a call for a constitutional model to be based on verse 44, Tabataba’i’s tafsir, in contrast, introduces a Shi’i element which founds, in combination with the political advocacy of Qutb and Sadr, the latter’s institutionalisation of the marja’iyya at the heart of the Islamic state.

The constitutional system of Sadr’s marja’iyya, thus founded in the Qur’an, is not only distinct when compared with the interpretation of other luminaries of twentieth-century Islam. By placing a Shi’i concept at the heart of the Islamic state advocated, it marks a break with Sadr’s early writings.

When in Iqtisaduna Sadr addressed briefly the question of the leadership in the Islamic state, he avoided’talking about the system of governance in Islam, and the question of the individual and the apparatus that should legally succeed the Prophet in his rule (wilaya) and prerogatives as a leader’.

Instead, through his masterpiece, Sadr’assume[d] in the analysis the presence of a legitimate ruler’.

Whenever the ruler’s role is mentioned in the’ discretionary sphere’,’ the area of vacuum’, mantaqat al-faragh,

which he should regulate, the word zvali al-amr (person in charge) or hakim shar’i (legal ruler) is used.

Thus was suggested a denotation far more universal than the Shi’i concept of marja’iyya prevailing in Sadr’s writings at the end of his life.

Stage 2 : the philosophical perspective

Khilafat al-Insan wa Shahadat al-Anbiya’ provided the foundation in the Qur’an of an institutional system in which the’ulama continued the role of the Prophets and of the Shi’i Imams at the head of the community. In Sadr’s last year, he also wrote another contribution on the state, Manabi1 al-Qudra fid-Dawla al-Islamiyya, which was part of a series of six booklets published in 1979 in a collection entitled Al-Islam Yaqud al-Hayat,’Islam guides life’.

Those works were clearly inspired by the victory of the Iranian Revolution, and they were meant to enhance its ideological impact. Before discussing the parallels between the constitutional Note which Sadr also wrote in 1979 for the collection, and which best represents his importance for the understanding of the present Iranian legal system, a presentation of the ideas advocated in Manabi’ al-Qudra will show Sadr’s philosophical perspective on power in the wake of the Iranian Revolution.

Manabi’ al-Qudra is a general work on the Islamic polity, and was probably meant by Sadr as a continuation of his long awaited study on the society.’The Islamic state is sometimes studied as a legal necessity because it institutes God’s rule on earth and incorporates the role of man in the succession of God’, writes Sadr at the outset of this book, in probable reference to the two other constitutional studies in the collection Islam guides life.’Sometimes’, he continues,’the Islamic state is studied in the light of this same truth, but from the point of view of its great achievement as civilization and immense potential which distinguish it from any other social experience.’

In Mana al-Qudra, this cultural aspect of the Islamic necessity’ is developed along two general lines, (i)’ the ideological (doctrinal,’aqa’idi) structure that distinguishes the Islamic state, and (2) the doctrinal and psychological structure of the individual Muslim in the reality of today’s Islamic world’.

As to the state, two elements constitute its connection with Islam. Like any other society, there is an aim for which the system vies. For the Islamic state, the aim is to take the way towards’ the absolute God’, and the values attached to Him,’justice, science, capacity, power, compassion, generosity, which constitute in their totality the object of the march of human society’.

But the other element is the one on which Sadr insists most in that year of revolution, the’liberation of man from the attachment to the world’.

This, writes Sadr, is not, like in many other countries or systems of the world, just’an imaginary conception’

Equality was lived and practised by the Prophet and by the first Imam, and equality in an Islamic state should not only be a mere word on the paper of a constitution. It must be implemented in practice.

This historical experience of the effective fight against inequality, injustice, and exploitation is then discussed at the level of the individual. The Muslim individual, writes Sadr, has retained, despite all adversities, a particular attachment to his religion.’This faded (bahita) Islamic doctrine has constituted, despite its quietism, a negative factor against any cultural framework or social system that does not emanate in thought and ideology from Islam’.

It is only by force and violence that those other systems have been sometimes able to control Muslim societies. Individuals have always shown in a spontaneous manner, as when they took up arms against an invader, or in a more consistent way, such as when they kept on paying alms to the poor as prescribed, that foreign control would always remain constrained by their attachment to their faith.

This survival of Islam is deeply rooted in history. For a Muslim, writes Sadr, there has always remained the example of the first Islamic state and the necessity to match its perfection. The dating of this state is slightly more precise than in Iqtisaduna:’The Islamic state offers the Muslim individual an example as clear as the sun, close to his heart... would one find any Muslim who does not have a clear picture of Islamic rule in the times of the Prophet and the Caliphate of’Ali and most of the period between them... ?’

In the Sources of Power in the Islamic State, there is actually little said on these sources. The study is mainly devoted to indicating, once more, the singularity of the Islamic state, both historically, as an experience which draws back on fourteen centuries of the attachment to Islam, and synchronically, as a constant quest for the perfection of God. Perhaps the most striking theme that emerges from this study is the insistence on’ detachment’, zuhdf, in the effort of’ clothing the earth with the frame of Heaven’ (ulbisat al-ard itar as-sama’).

This theme of justice has obviously re-emerged in the Middle East of 1979 as a central tenet of the assertion of political Islam.

The process that led to the narrowing of Sadr’s institutional basis of leadership developed concomitantly with a historical context that bore the stigma of the confrontation with the state.

The constitutional grounding of his thesis clearly reflects a care for a close control, in times of stress, of the revolutionary apparatus. In Iraq, in 1979-80, the choice for Sadr was between a loose oppositional front, which his last call’ to the people of Iraq’ typifies,

and the narrow appeal to the Shi’i ulama’ leadership followed both in the practice and the theory of verse 44. Iraq is indeed a complex society grouping ethnic and confessional groups, and Islam’s call faces a very difficult social terrain. In Iran, by contrast, the relative homogeneity of the religious composition of the population renders debatable the important sectarian variable. That there remains the ethnic dimension is of course important.

But for Sadr, in the enthusiasm that followed the victory of the Revolution, the ethnic problem mattered little. In 1979, he wrote his constitutional considerations in the Preliminary Legal Note on the Project of a Constitution for the Islamic Republic in Iran.

Stage 3: proposing a constitution for Iran

Manabi1 al-Qudra occupies the second stage of a three-level process in the adjustment of Sadr’s thought to the new realities of the Iranian Revolution.

In the first level, Khilafat al-Insan cjffers the celestial, theological level of the constitutional system in the peculiar Qur’anic reading of sura 5. As a second level, Manabi’’ al-Qudra constitutes a philosophical quest for the enduring significance of Islam throughout history. Lamha Fiqhiyya Tamhidiyya expresses the third stage of an actual, practical implementation of these theories in the process of the Islamic Revolution.

The exact date of this Note is important in assessing Sadr’s influence in Iran and in Iraq. It was completed on the 6th of Rabi’ al-Awwal 1399, corresponding to the 4th of February 1979.

That was before the final victory of the Iranian revolutionaries. The army in Iran was then still under the command of Shapur Bakhtiar, who was appointed Prime Minister just before the Shah’s departure, and a tense two-powers situation prevailed in the country. Only during the night of the 10/1 ith February, when the army rallied the revolution, did the last bastion of the Old Regime crumble.

At the time of writing the Note therefore, the concept of an Islamic Republic did not have a precise constitutional form, and the scheme forecast in Khumaini’s Najaf conferences

and in Taliqani’s constitutional articles

merely offered a general framework which lacked the minutiae of institutional articulation.

It would in any case have been impolitic and premature to go into details of that sort when the final battle had not yet been won, and Khumaini had too deftly avoided commitment to a precise societal scheme during the period spent in his French exile at Neauphle-le-Chateau to act rashly so close to victory.

For all these reasons, Sadr’s Note appears not to have been a comment on any pre-existing draft, despite its misleading title.

By asking Muhammad Baqer as-Sadr to express his thoughts on Khumaini’s’Islamic Republic’, the Lebanese Shi’i ulama’, who were anxious for more details on an eventual Islamic system, were not referring to any specific text.

The Note, therefore, is one of the early blueprints (probably even the earliest) of the Constitution finally adopted in Tehran. It is also remarkable in terms of its precedence over the debate on the Constitution of Iran in 1979, particularly in view of the text prepared by the first post-revolutionary Government and unveiled on June 18, which’made no mention of the doctrine of the deputyship of the faqih’.

Sadr’s Note was translated immediately and was widely circulated in Iran in both the Arabic original and the Persian translation.

In view of the stature then held by Sadr in religious circles, its influence is beyond doubt.

But there is more to it than its formal importance as the blueprint of Iranian fundamental law. The analysis of the Note vis-a-vis the final text of the Iranian Constitution, we would like to suggest, shows that the system adopted in Iran has incorporated almost invariably the proposals, hesitations and contradictions included, of Muhammad Baqer as-Sadr’s last important contribution.

‘ The Qur’anic state’, Sadr writes in the Note, is premised on an intrinsic dynamic towards the Absolute: God. It contains therefore the strength of the eternal and unfathomable character of God’s words. Borrowing a metaphor from surat al-kahf, Sadr juxtaposes’ the march of man towards God’ with the verse introducing the power of the Divine word:’ If the sea were ink to the words of my God, would it exhaust itself before God’s words.

The following are for Sadr the basic principles which, in the Note, offer the comprehensive picture of the Islamic state.

In Islamic fiqh, these principles are:

(1) Original sovereignty (al-wilaya bil-asl) rests only with God.

(2) Public deputyship (an-niyaba al-’amma) pertains to the supreme jurist (almujtahid al-mutlaq) habilitated by the Imam in accordance with the saying of the Lord of the Age (The Awaited Imam, imam al-’asr):’for actual events, go to the reporters of our stories, they hold evidence (hujja) for you as I am evidence to God’. This text shows that they are the referees (marja’) for all real and actual events insofar as these events are related to securing the application of the shari’a in life. Going to them as the reporters of stories and bearers of the law gives them the deputyship, in the sense of righteousness (qaymuma) in the application of the shari’a and the right to complete supervision (ishraf) from the shari’a’s angle.

(3) Leadership (succession, khilafa) of the nation (umma) rests on the basis of the principle of consultation (shura), which gives the Nation the right to selfdetermine its own affairs within the framework of constitutional supervision and control (raqaba) of the deputy of the Imam.

(4) The idea of the persons who bind and loose (ahl al-hall wal-(aqd), which was applied in Islamic history, and which, when developed in a mode compatible with the principle of consultation and the principle of constitutional supervision by the deputy of the Imam, leads to the establishment of a Parliament representing the nation and deriving (yanbathiq) from it by election.

This text, which comes at the end of the Note, sums up Sadr’s constitutional view as he applies it to Iran. From the outset, the principle of God’s sovereignty is asserted as an Islamic principle of government deliberately put forward in contrast with Western theories. This quotation is followed by a brief review of the alternative constitutional theories prevailing in the West. On the basis of his Islamic model, which obtains from a divine sovereignty combined with the amalgamation of the principle of popular representation by a Parliament-elect and the supervision of jurists, Sadr rejects’ the theory of force and domination’ (in reference to Hobbes),’ the theory of God’s forced mandate’ (in reference to the medieval Divine Right of Kings, which he puts in contrast to his notion of a divine sovereignty actuated by Parliament and the jurists),’the theory of the social contract’ (in direct reference to Rousseau, and indirectly to Locke and other social contract theorists), and’ the theory of the development of society from the family’ (in probable reference to Friedrich Engels’ Family).

In the general principles adopted by the Iranian Constitution of 1979, it is difficult not to be struck by the similarities with Sadr’s work. The first principle stated by Sadr is echoed in Article 2 (1) of the Constitution, which declares that’the Islamic Republic is a system based on the belief... in the sovereignty of God’. Article 56 repeats the principle further:’Absolute sovereignty over the world and over man is God’s. He grants man the right of sovereignty over his social destiny, and no person is allowed to usurp or exploit this right.’

This principle, which looks as if it were too general to carry any consequences, is useful as a pointed contrast to the traditional vesting of ultimate power in people by modern constitutions.

Such divine sovereignty is emphasised by Sadr

in contrast’ to the divine right that the tyrants and kings have exploited for centuries’,

and is clearly directed against the practice of the Iranian Shah. The principle is translated institutionally in two important directions. The first is the limits put on the powers of the Executive and Legislature vis-a-vis the jurists entrusted with the protection of the shari’a. The second consequence touches upon the absoluteness of the right of the individual to property. In Sadr’s scheme, there can be no such absolute right to property, since man is at best a lessee of riches pertaining to God, in an environment over which only God can claim absoluteness.

The central role of the jurist as interpreter and protector of the shari’a, advocated by Khumaini in 1970 but articulated by Sadr in his contributions of 1979, appears paramount both in the Note and in the text of the Iranian Constitution, which states in Article 5 that’ during the Occultation of the Hidden Imam (vali-e asr),... the responsibility for state affairs (yilayat-e amr) and the leadership of the nation are entrusted to a just Qadel)..., competent (aga be-zaman) jurist (faqih)’ For Sadr, as in the text quoted earlier, the wilaya’amma, which is the responsibility for the affairs of the state, rests ultimately with the supreme jurist, who must be just (ladel) and competent (kafu’).

Thus, in Sadr and Khumaini’s proposals, as well as in the Iranian Constitution, final decision rests with the holder of a position which Sadr calls marja1 qa’ed

or mujtahid mutlaq

Khumaini faqih’alem’adel,

and the Iranian Constitution rahbar, Leader (Art. 5, Art. ioyff.).

If the supremacy of the jurist is final, it is not absolute. In Sadr’s proposals, the system is a system of law, which is binding for all, including the marja’, who enjoys no particular immunity:’ Government is government of law, in that it respects law in the best way, since the shari’a rules over governors and governed alike.’

Khumaini wrote similarly in 1970, insisting in Wilayat al-Faqih that’ the government of Islam is not absolute. It is constitutional... in that those who are entrusted with power are bound by the ensemble of conditions and rules revealed in the Qur’an and the Sunna... Islamic government is the government of divine law.’

This is echoed in the description of the rahbar in the Iranian Constitution.

Article 112 states that’ the Leader or the members of the Leadership Council are equal before the law with the other members of the country (keshvar)’.

It is no surprise to find mention of the equality for all, including the Leadership, before the law. But the real limitation on the power of the Leader rests in the definition of his ultimate arbitration, or supervision, against the other powers established by the Constitution.

The model of this supervision is exposed in the scheme of separation of powers which has been implemented in Iran. The blueprint of the model appears in its clearest expression in Sadr’s Note. But it goes back, in many of its characteristics, to the Shi’i legal structure inherited since the triumph of Usulism, and later reproduced and refined in the educational system of the schools of law. This singularity, on the level of the state, transforms the system in Iran, as well as Sadr’s scheme, into a two-level articulation of the separation of powers.

The two-tier separation of powers

With the sovereignty vested in God, and the mujtahid-leader being the mouthpiece and the ultimate guarantor of the implementation of divine law, Sadr’s system (and in this the debt of Iran’s constitution is much heavier to him than to Khumaini) is also premised on emanations of sovereignty which derive from the people,

or as appears more frequently in his constitutional treatise, in the umma (the Muslim community). In the text quoted earlier, these emanations of the people are vested, according to principles 3 and 4, in the establishment of a consultation and consequently of a parliament and a presidency elected directly by the people. This dual emanation of sovereignty is at the root of the double-tier separation of powers. In the Note, consultation and election are further developed:

The legislative and executive powers are exercised (usnidat mwnarasatuha) by the people (umma). The people are the possessors of the right to implement these two powers in ways specified by the Constitution. This right is a right of promotion (succession, istikhlaf) and control (ri’aya) which results from the real source of powers, God Almighty.

In practice, continues Sadr, the control (ri’aya) is exercised through the election by the people of the head of the executive power, after confirmation by the marja’iyya, and through the election of a parliament (called majlis ahl al-hall wal-’aqd), which is in charge of confirming the members of government appointed by the Executive,

and’passing appropriate legislation to fill up the discretionary area’.

Sadr’s constitutional proposal retains a traditional feature of modern constitutionalism, the separation of powers between the Executive, the Legislature, and the Judiciary. The last power, in its traditional form, is included in the proposal as a’supreme court to hold account on all contraventions of the aforementioned areas’, and as an ombudsman, which Sadr calls the diwan al-mazalim, and which acts to redress the wrongs brought on citizens.

At the level of the separation of powers, there is little new. Most countries in the world which are not based on the power of a single party advocate in their constitution some form of division of powers deriving from the Montesquieu model: in general, a separation between the executive, the legislative, and the judicial branches of government, with each branch checking the power of the other and protecting its own domain against the others’ encroachment. The Iranian Constitution does not differ in this respect. In its broad lines, it follows Montesquieu’s scheme. The Executive’s structure, mode of election and prerogatives are stipulated in the Constitution’s chapter 9 (Arts. 113-32 on the president, Arts. 133-42 on the Prime Minister and the Cabinet). The Legislature is governed by Arts. 62-99 in chapter 6, and the Judiciary by the rules of chapter 11 (Arts. 156-74). Some of the detailed points of the system will be further discussed in the next chapter, but it can be already noted that this aspect of the separation of powers offers no novelty in the Islamic Republic’s constitutionalism.

It is the second tier of separation of powers which lends originality to Sadr’s system, as well as to the Iranian Constitution. The concept of marjaiyyaa, wherein lies the originality, is at the heart of that constitutional model.

Prerogatives of the marja’ jrahbar

In contrast to Khumaini’s 1970 lectures, the practical concern is prominent in Sadr’s Note, as well as in the Iranian Constitution. The power of xhefaqih, which for Khumaini was the concluding point of his argument in Islamic government, has become the starting point of Sadr and the victorious Iranian constituent actors. In 1979, the materialisation of this power and its institutionalisation were the major concern of the Iraqi leader and the Iranian followers of Khumaini.

The peculiarity of the marja’iyya as an institution resides in two dimensions: its prerogatives, and its internal structure in the light of history.

A major dichotomy appears in the prerogatives of the marja’. Though his essential function is of a judicial nature, and consists in securing the compatibility of all activities in the country within the framework offered by Islamic law, the marja’ also retains strong executive privileges. For Sadr,’the marja’ is the supreme representative of the state and the highest army commander’.

Defence responsibilities are directly echoed in Article 110 of the Iranian Constitution, which confers on the Leadership the command of the army and of the revolutionary guards. As to the supremacy in the state, it comes indirectly in Article 113:’The president of the republic holds the highest official position in the country after the Leadership.’ Also, Sadr’s marja’ puts the stamp of approval on the candidates for the Presidency. The wording in this case is interesting in view of the options chosen by the Iranian Constitution. In the Note,’the marja’ nominates (yurashshih) the candidates [to the Presidency], or approves the candidacy of the individual or individuals who seek to win [the position of] heading the Executive’.

In the Iranian Constitution, a similar distinction is made between the approval of the candidate-elect, which is a prerogative of the Leader after the elections (Arts. 110-14), and the screening of the candidates to the Presidency, which is the prerogative of the Council of Guardians.

The marja’ appoints the high members of the Judiciary in Sadr’s system,

as does the Leader according to Articles 110-12 of the Iranian constitution.

He also appoints the jurists who sit on the Council of Guardians of the Constitution (Arts. 110-11). In Sadr’s Note, the marja’iyya’decides on the constitutionality of the laws promulgated by the Parliament (majlis ahl alhall wal-’aqd) in the discretionary area’.

The nuance in these prerogatives is important. In the Iranian practice of the post-revolutionary area, the Council of Guardians did in fact decide on the constitutionality of laws, and this essential task was the major cause of the institutional crisis which culminated in a major revision of the Constitution. In effect, Sadr’s vesting of the direct control of constitutionality in the marja’iyya appears in retrospect as a wiser measure than the stipulations of the Iranian text, which separates between the marja’/rahbar and the Council of Guardians. This last argument will appear more clearly in the context of the crisis described in the next chapter.

Evidently, the powers of the marja’/rahbar, who also decides on peace and war,

are wide-ranging, and, to some extent, defeat the whole traditional scheme of separation of powers. The Leader is not a marginal honorific figure. He must act on several issues positively, and he appoints several high dignitaries in the government, as well as in the courts. In effect, the importance of the marja’iyya/shuray-e rahbari undermines the division between the Executive, the Legislature, and the Judiciary by the sole merit of its powerful existence. In theory, the three traditional branches check each other, but the presence of the marja’iyya creates an authority of last resort which is superior to them. The separation of powers becomes a double division, and the multi-layered combinations of checks and balances make the dialectic of the traditional system appear simple in contrast. At the same time, the marjaiyyaa under Khumaini has not developed a day-to-day smooth mechanism of implementation. This uneasy and complex system will appear even more so in the light of its internal structure.

Internal structure and historical legitimisation

The key text in Sadr’s work in terms of the originality of the constitutional model for Iran relates to the internal structure of the marjaiyyaa. It derives from his observation that’the marjaiyyaa is the legitimate expression (mulabbir shar’i) of Islam, and the marja’ is the deputy (na’eb) of the Imam from the legal point of view’.

The following mechanism is devised for the implementation of the principle:

The marja’ appoints a council of (yadumm) one hundred spiritual intellectuals (muthaqqafin ruhiyyin) and comprises a number of the best ulama’ of the hauza, a number of the best’delegate’ulama’ [zuukala’, i.e.’ulama charged with a specific mandate], and a number of the best Islamic orators (khutaba’), authors and thinkers (mufakkirin). The council must include not less than ten mujtahids. The marjaiyyaa carries out its authority through this council.

Much of the uncertainty in the constitutional arrangement in Iran can be read into the equivalent provisions. The main aspect of this uncertainty derives from the vicious circle which can be detected in the arrangement.

The authority of the highest power is understood to be exercised through the council of the marjaiyyaa. But the council is appointed by a sole person, who is the marja’. In turn, the marjaiyyaa as a collective body is in charge, as Sadr points out later, of’ nominating the marja1 by the majority of its members’

Who nominates whom, of the marja1 as an individual, or of the marjaiyyaa as a collective body, is blurred and seemingly contradictory.

One can see the reflection of these provisions in the text of the Iranian Constitution, which solves the contradiction only in part. The three relevant articles on the marja’’ and the marjaiyyaa Articles 5, 107 and 108, stipulate that:

If there is no such faqih [as the one specified in the first lines of this article,’ whom the majority of people have accepted and followed’], to have won the majority, the Leader [rahbar, which is the equivalent of marja6] or Council of Leadership [shura-ye rahbari, marjaiyyaa] composed of thefuqaha who fulfill the qualification stipulated in Article 107 will be entrusted with that authority [of velayat-e atnr and imamat-e ummat]. (Art. 5)

Otherwise [i.e. if there is no faqih who has been adopted’by a decisive majority of the people... like Ayat Allah Khumaini’], the experts elected by the people shall consult about all those considered competent to be vested with such authority and leadership.

If one such authority is known to be preeminent above all others, he shall be appointed as the Leader of the nation; otherwise, three or five authorities fully qualified for Leadership shall be appointed as members of the Council of Leadership. (Art. 107)

Art. 108 presents the status and competence of’the experts’ (khubregan):

The law related to the number and qualification of experts, the way to elect them and the internal regulations of their session for their first assembly will be decided and approved by the majority of fuqaha of the first Council of Guardians, and endorsed by the Leader of the revolution [Khumaini]. Then, any alteration or revision of the law will be decided by the Assembly of Experts.

In theory then, the Iranian Constitution solved what had appeared contradictory in Sadr’s text by means of a mechanism which allowed the Council of Guardians to draft legislation regulating the choice and competence of the Assembly of Experts, subject to the approval of Khumaini qua leader of the revolution.

In turn, this Assembly would, in its first meeting, readjust the law, and then proceed regularly with its work. But beyond this, the members of the Assembly of Experts had to be elected by the people. So far, the mechanism, though complex, seems to solve Sadr’s vicious circle.

But the problem arises again from the interplay of historical legitimacy and popular election in relation to the Leader or the Council of Leadership. The text of the Iranian Constitution suggests that the Leader’must be accepted by the majority of the people’ (Art. 5),’as has been the case’(Art. 108) with Ay at Allah al-Khumaini, who is specified by name. Sadr had suggested a similar scheme, which was however more elaborate than the mere reference to the persona of Khumaini as the historical model to follow:’ The marjaiyyaa is a social and objective reality of the nation (haqiqa ijtimaiyyaa mawduliyya fil-umma), which rests on the basis of the public legal balance (rnawazin). In practice, it is effectively represented in the marjai and leader of the revolution [inqilab, the Persian word for revolution rather than the Arabic word thawra], who has led the people for twenty years and who was followed until victory by the whole nation.’

Sadr, like the Iranian revolutionaries, was aware of the uncertainty of a repetition of the Khumaini phenomenon. An institutional scheme had to be devised,’as a higher concept (maqula lulya) of the Islamic state in the long run’. The person who could be such marja1 had to embody that concept by:

(1) Having the qualifications of a religious marja’’ who is capable of absolute ijtihad and justice;

(2) Exhibiting a clear intellectual line through his works and studies which proves his belief in the Islamic state and the necessity to protect it.

(3) Showing that his marja’iyya in effect in the umma has been achieved by the normal channels followed historically.

The first condition mentioned in this paragraph echoes the usual requirements in the Shi’i tradition of the’ulama hierarchy. The second condition is a requirement which helps separate politically minded from a-political ‘ulama. The third paragraph is the most interesting, because it reveals in so many words the exact problem faced by the institutionalisation, at the level of a state, of the structure of the Shi’i colleges of Najaf.

‘ The normal channels followed historically’ refers to what the previous chapter was trying to analyse, and explains how the rahbar of the Iranian Constitution corresponds to thefaqih of Khumaini’s Islamic Government, to the ra’is of Muhammad Taqi al-Faqih’s University of Najaf, and to the marja1 qa’ed of Sadr’s Note. All denominations stem from these normal channels of the Shi’i hierarchy, with the uncertainty and vagueness which made it so’extremely difficult’ for Muhammad Taqi al-Faqih, back in the 1940s, to explain how the ra’is of the Shi’i world was elected or chosen. This uncertainty can be read into the fine lines of Art. 107 of the Iranian Constitution, which requires the Assembly of Experts to choose as Leader’one such authority who is known to be pre-eminent above all others’. This’knowledge’ is none other than Sadr’s’normal channels followed historically’, Muhammad Taqi al-Faqih’s’protracted democratic process’, and beyond, the’living mujtahid’ of the Usuli tradition. What constituted a long and complicated process was reduced by the Iranian constitution to an ad hoc decision of the Assembly of Experts, which was entrusted with the appointment of the’Leader’. In strict Shi’i law, however, nothing forces the lay person to accept that leader as the mujtahid whom he or she chooses to follow.

It is worth noting that the reason why this difficulty did not develop into a major contradiction of the Iranian system of government had to do precisely with the stature of Khumaini, and the exceptional circumstances which brought him to power in Tehran. The absence of Khumaini reopens the wound of the protracted process of choice. Even if the Assembly of Experts can choose a’Leader’, the choice will always be under threat of the re-emergence of the historical Shi’i process of choice, in which, in theory, the more knowledgeable will eclipse the less knowledgeable at the head of the community, even if the former emerges after the latter has acceded to power.

This is one of the most intricate problems faced by the system. The choice of the Leader-mar/a’ is an open and repetitive process according to the theory of Shi’i law. In the Iranian Constitution in contrast, the process is constrained.

The other problem is also rooted in the discrepancy between the Shi’i legal tradition, which makes of the marja1 a primus inter pares, and the mechanisms of the Iranian system. That Khumaini played since the establishment of the Islamic Republic a role of undisputed leader does not mean that the same would be true for another leader.

Before Khumaini’s death, the succession problem was relatively marginalised by the unquestioned supremacy of’the leader of the revolution’. Now that he is no more to provide a last resort to the conflicts between institutions, the Iranian constitutional system faces a situation of uncertainty on the level of Leadership, which will be reinforced by the’normal channels’ of the Shi’i marja’iyya.

The quietist dominant trend of the’ulama and the diversity of maraji’ has traditionally rendered marginal any conflict at the top of the hierarchy. Once the system was institutionalised, the mild competition between the scholars would have easily acquired the character of a serious constitutional crisis.

Khumaini’s presence alleviated that danger and kept the system going. It will be interesting to see how an inevitably less charismatic Leader will react to the pressure of events.

There were other essential problems deriving from the two-tier separation of powers which characterises the intricate structure of the Iranian constitution. The decade of constitutional developments related to these problems is examined next.

0%

0%

Author: CHIBLI MALLAT

Author: CHIBLI MALLAT