CHAPTER II: THE NEO‑PLATONIC ARISTOTELIANS OF PERSIA

With the Arab conquest of Persia, a new era begins in the history of Persian thought. But the warlike sons of sandy Arabia whose swords terminated, at Nahāwand, the political independence of this ancient people, could hardly touch the intellectual freedom of the converted Zoroastrian.

The political revolution brought about by the Arab conquest marks the beginning of interaction between the Aryan and the Semitic, and we find that the Persian, though he lets the surface of his life become largely semitised, quietly converts Islam to his own Aryan habits of thought. In the West the sober Hellenic intellect interpreted another Semitic religion ‑Christianity; and the results of interpretation in both cases are strikingly similar. In each case the‑ aim of the interpreting intellect is to soften the extreme rigidity of an absolute law imposed on the individual from without; in one word it is an endeavour to internalise the external. This process of transformation began with the study of Greek thought which, though combined with other causes, hindered the growth of native speculation, yet marked a transition from the purely objective attitude of Pre‑Islamic Persian Philosophy to the subjective attitude of later thinkers. It is, I believe, largely due to the influence of foreign thought that the old monistic tendency when it reasserted itself about the end of the 8th century, assumed a much more spiritual aspect; and, in its latter development, revivified and spiritualised the old Iranian dualism of Light and Darkness. The fact, therefore, that Greek thought roused into fresh life the subtle Persian intellect, and largely contributed to, and was finally assimilated by the general course of intellectual evolution in Persia, justifies us in briefly running over, even though at the risk of repetition, the systems of the Persian Neo‑Platonists who, as such, deserve very little attention in a history of purely Persian thought.

It must, however, be remembered that Greek wisdom flowed towards the Moslem east through Harrān and Syria. The Syrians took up the latest Greek speculation i.e. Neo‑Platonism and transmitted to the Moslem what they believed to be the real philosophy of Artistotle. It is surprising that Mohammedan Philosophers, Arabs as well as Persians, continued wrangling over what they believed to be, the real teaching of Aristotle and Plato, and it never occurred to them that for a thorough comprehension of their Philosophies, the knowledge of Greek language was absolutely necessary. So great was their, ignorance that an epitomised translation, of the Enneeads of Plotinus was accepted as āTheology of Aristotle.ā It took them centuries to arrive at. a clear conception of the two great masters of Greek thought and it is doubtful whether they ever completely understood them. Avicenna is certainly clearer and more original than Al‑Fārābī and Ibn Maskawaih; and the Andelusian Averroes, though he is nearer to Aristotle than any of his predecessors, is yet far from a complete grasp of Aristotle's Philosophy. It would, however, be unjust to accuse them of servile imitation. The history of their speculation is one continuous attempt to wade through a hopeless mass of absurdities that careless translators of Greek Philosophy had introduced. They had largely to rethink the Philosophies of Aristotle and Plato. Their commentaries constitute, so to speak, an effort at discovery, not exposition. The very circumstances which left them no time to think out independent systems of thought, point to a subtle mind, unfortunately cabined and cribbed by a heap of obstructing nonsense that patient industry had gradually to eliminate, and thus to window out truth from falsehood. with these preliminary remarks we proceed to consider Persian students of Greek Philosophy individually.

1. IBN MASKAWAIH

(d. 1030)

Passing over the names of Saraḵẖsīī

, Fārābī who was a Turk, and the Physician Rāzī (d. 932 A.D.) who true to his Persian habits of thought, looked upon light as the first creation, and admitted the eternity of matter, space and time, we come to the illustrious name of Abu 'Ali Muhammad Ibn Muhammad Ibn Ya'qub, commonly known as Ibn Maskawaih ‑the treasurer of the Buwaihid Sultan' Adaduddaula ‑one of the most eminent theistic thinkers, physicians, moralists and historians of Persia. I give below a brief account of his system from his well‑known work Al Fauz al‑Asg̱ẖar, published in Beirët.

1. The existence of the ultimate principle

Here Ibn Maskawaih follows Aristotle, and reproduces his argument based on the fact of physical motion. All bodies have the inseparable property of motion which covers all form of change, and does not proceed from the nature of bodies themselves. Motion, therefore, demands an external source of prime mover. The supposition that motion may constitute the very essence of bodies, is contradicted by experience. Man, for instance, has the power of free movement; but, on the supposition, different parts of his body must continue to move even after they are severed from one another. The series of moving causes, therefore, must stop at a cause which, itself immovable, moves everything else. The immobility of the Primal cause is essential; for the supposition of motion in the Primal cause would necessitate infinite regress, which is absurd.

The immovable mover is one. A multiplicity of original movers must imply something common in their nature, so that they might be brought under the same category. It must also imply some point of difference in order to distinguish them from each other. But this partial identity and difference necessitate composition in their respective essences; and composition, being a form of motion, cannot, as we have shown, exist in the first cause of motion. The prime mover again is eternal and immaterial. Since transition from non‑existence to existence is a form of motion; and since matter is always subject to some kind of motion, it follows that a thing which is not eternal, or is, in any way, associated with matter, must be in motion.

2. The Knowledge of the Ultimate

All human knowledge begins from sensations which are gradually transformed into ' perceptions. The earlier stages of intellection are completely con. ditioned by the presence of external reality. But the progress of knowledge means to be able to think without being conditioned by matter. Thought begins with matter, but its object is to gradually free itself from the primary condition of its own possibility. A higher stage, therefore, is reached in imagination ‑ the power to reproduce and retain in the mind the copy or image of a thing without reference to the external objectivity of the thing itself. In the formation of concepts thought reaches a still higher stage in point of freedom from materiality though the concept, in so far as it is the result of comparison and assimilation of percepts, cannot he regarded as having completely freed itself from the gross cause of sensations. But the fact that conception is based on perception, should not lead us to ignore the great difference between the nature of the concept and the percept, The individual (percept) is undergoing constant change which affects the character of the knowledge founded on mere perception. The knowledge of individuals, therefore, lacks the element of permanence. The universal (concept), on the other hand, is not affected by the law of change. Individuals change; the universal remains intact. It is the essence of matter to submit to the law of change: the freer a thing is from matter, the less liable it is to change. God, therefore, being absolutely free from matter, is absolutely changeless; and it is His complete' freedom from materiality that makes our conception of Him difficult.or impossible. The object of all Philosophical training is to develop the power of āideationā or contemplation on pure concepts, in order that constant practice might make possible the conception of the absolutely immaterial.

3. How the one creates the many

In this connection it is necessary, for the sake of clearness, to divide Ibn Maskcawaih's investigations into two parts:‑

(a) That the ultimate agent or cause created the Universe out of nothing. Materialists, he says, hold the eternity of matter, and attribute form to the creative activity of God. It is, however, admitted that when matter passes from one form into another form, the previous form becomes absolutely non. existent. For if it does not become absolutely non-existent, it must either pass off into some other body, or continue to exist in the same body. The first alternative is contradicted by every‑day experience‑ If we transform a ball of wax into a solid square, the original rotundity of the ball does not pass off into some other body. The second alternative is also impossible; for it would necessitate the conclusion that two contradictory forms e.g., circularity and length, can exist in the same body. It, therefore, follows that the original form passes into absolute non‑existence, when the new form comes into being. This argument proves conclusively that, attributes i. e. form, colour etc., come into being from pure nothing. In order to understand that the substance is also non‑eternal like the attribute, we should grasp the truth of the following propositions:

1. The analysis of matter results in a number of different elements, the diversity of which is reduced to one simple element.

2. Form and matter are inseparable: no change in matter can annihilate form.

From these two propositions, Ibn Maskawaih concludes that the substance had a beginning in time. Matter like form must have begun to exist; since the eternity of matter necessitates the eternity of form which, as we have seen, cannot be regarded as eternal.

(b) The process of creation. What is the cause of this immense diversity which meets us on all sides? How could the many be created by one? When, says the Philosopher, one cause produces a number of different effects, their multiplicity may depend on any of the following reasons:

1. The cause may have various powers. Man, for instance, being a combination of various elements and powers. may be the cause of various actions.

2. The cause may use various means to produce a variety of effects.,

3. The cause may work upon a variety of material.

None of these propositions can be true of the nature of the ultimate cause‑God. That he possesses various powers, distinct from one another, is manifestly absurd; since his nature does not admit of composition. If he is supposed to have employed different means to produce diversity. who is the creator of these means? If these means are due to the creative agency of some cause other than the ultimate cause, there would be a plurality of ultimate causes. If, on the other hand, the Ultimate Cause himself created these means, he must have required other means to create these means. The third proposition is also inadmissible as a conception of the creative act. The many cannot flow from the causal action of one agent. It, therefore, follows that we have only one way out of the difficulty ‑ that the ultimate cause created only one thing which led to the creation of another. Ibn Maskawaih here enumerates the usual Neo‑Platonic emanations gradually growing grosser and grosser until we reach the primordial elements, which combine and recombine to evolve higher and higher forms of life. Shiblī thus sums up Ibn Maskawaih's theory of evolution

:

The combination of primary substances produced the mineral kingdom, the lowest form of life. A higher stage of evolution is reached in the vegetable kingdom. The first to appear is spontaneous grass then plants and various kinds of trees, some of which touch the border‑land of animal kingdom, in so far as they manifest certain animal characteristics. Intermediary between the vegetable kingdom and the animal kingdom there is a certain form of life which is neither animal nor vegetable, but shares the characteristics of both (e.g., coral). The first step beyond this intermediary stage of life, is the development of the power of movement, and the sense of touch in tiny worms which crawl upon the earth. The sense of touch, owing to the process of differentiation, develops other forms of sense, until we reach the plane of higher animals in which intelligence begins to manifest itself in an ascending scale. Humanity is touched in the ape which undergoes further development, and gradually develops erect stature and power of understanding similar to man. Here animality ends and humanity begins.”

4. The Soul

In order to understand whether the soul has an independent existence, we should examine the nature of human knowledge. It is the essential property of matter that it cannot assume two different forms simultaneously. To transform a silver spoon into a silver glass, it is necessary that the spoon‑form as such should cease to exist. This property is common to all bodies, and body that lacks it cannot be regarded as a body. Now when we examine the nature of perception, we see that there is a principle in man which, in so far as it is able to know more than one thing at a time, can assume, so to say, many different forms simultaneously. This principle cannot be matter, since it lacks the fundamental property of matter. The essense of the soul consists in the power of perceiving a number of objects at one and the same moment of time. But it may be objected that the soul‑principle may be either material in its essence, or a function of matter. There are, however, reasons to show that the soul cannot be a function of matter.

(a) A thing which assumes different forms and states, cannot itself be one of these forms and states. A body which receives different colours should be, in its own nature, colourless. The soul, in its perception of external objects, assumes, as it were, various forms and states; it, therefore, cannot be regarded as one of those forms. Ibn Maskawaih seems to give no countenance to the contemporary Faculty‑ Psychology; to him different mental states are various transformations of the soul itself.

b) The attributes are constantly changing; there must be beyond the sphere of change, some permanent substratum which is the foundation of personal identity.

Having shown that the soul cannot be regarded as a function of matter, Ibn Maskawaih proceeds to prove that it is essentially immaterial. Some of his arguments may be noticed:

1. The senses, after they have perceived a strong stimulus, cannot, for a certain amount of time, perceive a weaker stimulus. It is, however, quite different with the mental act of cognition.

2. When we reflect on an abstruse subject, we endeavour to completely shut our eyes to the objects around us, which ‑we regard as so many hindrances in the way of spiritual activity. If the soul is material in its essence, it need not., in order to secure unimpeded activity, escape from the world of matter.

3. The perception of a strong stimulus weakens and sometimes injures the sense. The intellect, on the other hand, grows in strength with the knowledge of ideas and general notions.

4. Physical weakness due to old age, does not affect mental vigour.

5. The soul can conceive certain propositions which have no connection with the sense‑data. The senses, for instance, cannot perceive. that two contradictories cannot exist together.

6. There is a certain power in us which rules over physical organs, corrects sense‑errors, and unifies all knowledge. This unifying principle which reflects over the, material brought before it through the science‑channel, and, weighing the evidence of each sense,. decides the character of rival statements, must itself stand above the. sphere of matter.

The combined force of these considerations, says Ibn Maskawaih, conclusively establishes the truth of the proposition‑that the soul is essentially immaterial. The immateriality of the soul signifies its immortality; since mortality is a characteristic of the material.

2. AVICENNA (d. 1037)

Among the early Persian Philosophers, Avicenna alone attempted to construct his own system of thought. His work, called “Eastern Philosophy”, is still extant; and there has also come down to us a fragment

in which the Philosopher has expressed his views on the universal operation of the force of love in nature. It is something like the contour of a system, and it is quite probable that Ideas expressed therein were afterwards fully worked out.

Avicenna defines “Love” as the appreciation of Beauty, and from the standpoint of this definition he explains that there are three categories of being:

1. Things that are at the highest point of perfection.

2. Things that are at the lowest point of perfection.

3. Things that stand between the two poles of perfection. But the third category has no real existence; since there are things that have already attained the acme of perfection, and there are others still progressing towards perfection. This striving for the ideal is love's movement towards beauty which, according to Avicenna, is identical with perfection. Beneath the visible evolution of forms is the force of love which actualises all striving, movement, progress. Things are so constituted that they hate non‑existence, and love the joy of individuality in various forms. The indeterminate matter, dead in itself, assumes, or more properly, is made to asume by the inner force of love, various forms, and rises higher and higher in the scale of beauty. The operation of this ultimate force, in the physical plane, can be thus indicated:

1. Inanimate objects are combinations of form, matter and quality. Owing to the working of this mysterious power, quality sticks to its subject or substance; and form embraces indeterminate matter which, impelled by the mighty force of love, rises from fomī to form.

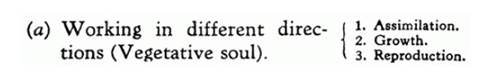

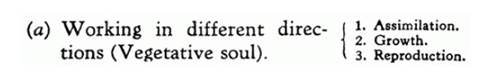

2. The tendency of the force of love is to centralise itself In the vegetable kindom, it attains a higher degree of unity or centralisation; though the soul still lacks that unity of action which it attains afterwards. The processes of the vegetative soul are

(a) Assimilation.

(b) Growth.

(c) Reproduction.

These processes, however, are nothing more than so many manifestations of love. Assimilation indicates attraction and transformation of what is external into what is internal. Growth is love of achieving more and more harmony of parts; and reproduction means perpetuation of the kind, which is only another phase of love.

3. In the animal kingdom, the various operations of the force of love are still more unified. It does preserve the vegetable instinct of acting in different directions; but there is also the development of temperament which is a step towards more unified activity. In man this tendency towards unification manifests itself in self‑consciousness. The same force of ānatural or constitutional love,ā is working in the life of beings higher than man. All things are moving towards the first Beloved the Eternal Beauty. The worth of a thing is decided by its nearness to, or distance from, this ultimate principle.

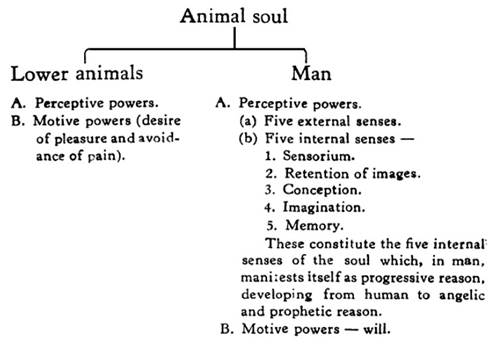

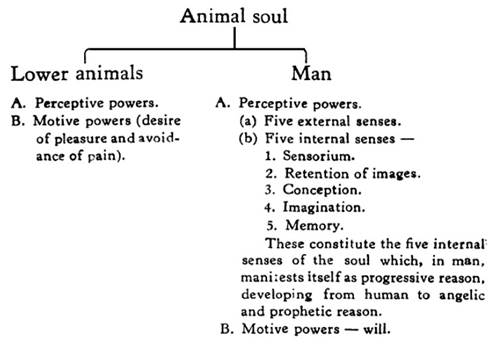

As a physician. however, Avicenna is especially interested in the nature of the Soul. In his times, moreover, the doctrine of metempsychosis was gating more and more popular. He, therefore, discusses the nature of the soul, with a view to show the falsity of this doctrine. It is difficult, he says, to define the soul; since it manifest., different powers and tendencies in different planes of being. His view of the various powers of the soul can be thus represented:

1. Manifestation as unconscious activity

(b) Working in one direction and securing uniformity of action‑growth of temperament.

2. Manifestation as conscious activity

(a) As directed to more than one object

(b) As directed to one object ‑ The soul of the spheres which continue in one uniform motion.

In his fragment on “Nafs” (soul) Avicenna endeavours to show that a material accompaniment is not necessary to the soul. It is not through the instrumentality of the body, or some power of the body, that the soul conceives or imagines; since if the soul necessarily requires a physical medium in conceiving other things, it must require a different body in order to conceive the body attached to itself. Moreover, the fact that the soul is immediately self conscious‑ conscious of itself through itself‑conclusively shows that in its essence the soul is quite independent of any physical accompaniment. The doctrine of metempsychosis implies, also, individual Pre‑existence. But supposing that the soul did exist before the body, it must have existed either as one or as many, The multiplicity of bodies is due to the multiplicity of material forms, and does not indicate the multiplicity of souls. On the other hand, if it existed as one, the ignorance or knowledge of A must mean the ignorance or knowledge of B; since the soul is one in both. These categories, therefore, cannot be applied to the soul. The truth is, says Avicenna, that body and soul are contiguous to each other, but quite opposite in their respective essences. The disintegration of the body does not necessitate the annihilation of the soul. Dissolution or decay is a property of compound, and not of simple, indivisible, ideal substances. Avicenna, then denies pre‑existence, and endeavors to show the possibility of disembodied conscious life beyond the grave.

We have run over the work of the early Persian Neo‑Platonists among whom, as we have seen, Avicenna alone learned to think for himself. Of the generations of his disciples ‑Behmenyarl. Abu'l‑Ma'mëm, of Isfahān, Ma'sumī Ab u'l‑'Abbās, Ibn Tāhir

‑ who carried on their master's Philosophy, we need not speak. So powerful was the spell of Avicenna's personality that even long after it had been removed, any amplification or modification of his views was considered to be an unpardonable crime. The old Iranian idea of the dualism of Light and Darkness does not act as a determining factor in the progress of Neo‑Platonic ideas in Persia, which borrowed independent life for a time, and eventually merged their separate existence in the general current of Persian speculation. They are therefore, connected with the course of indigenous thought only in so far as they contributed to the strength and expansion of that monistic tendency, which manifested itself early in the Church of Zoroaster; and, though for a time hindered by the theological controversies of Islām, burst out with redoubled force in later times to extend its titanic grasp to all the previous intellectual achievements of the land of its birth.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

0%

0%

Author: Dr. Muhammad Iqbal

Author: Dr. Muhammad Iqbal