CHAP. V. ṢŪFĪSM

§ I. The origin and Ourānic Justification of Ṣūfīism

It has become quite a fashion with modern oriental scholarship to trace the chain of influences. Such a procedure has certainly great historical value, provided it does not make us ignore the fundamental fact, that the human mind possesses an independent individuality, and, acting on its own initiative, can gradually evolve out of itself, truths which may have been anticipated by other minds ages ago. No idea can seize a people's soul unless, in some sense, it is the people's own. External influences may wake it up from its deep unconscious slumber; but they cannot, so to speak, create it out of nothing.

Much has been written about the origin of Persian Suflism; and, in almost all cases, explorers of this most interesting field of research have exercised their ingenuity in discovering the various channels through which the basic ideas of Sufīism might have travelled from one place to another. They seem completely to have ignored the principle, that the full significance of a phenomenon in the intellectual evolution of a people, can only be comprehended in the light of those pre-existing intellectual, political, and social conditions which alone make its existence inevitable. Von Kremer and Dozy derive Persian Sufīism from the Indian Vedanta; Merx and Mr. Nicholson derive it from Neo-Platonism; while Professor Browne once regarded it as Aryan reaction against an unemotional semitic religion. It appears to me, however, that these theories have been worked out under the influence of a notion of causation which is essentially false. That a fixed quantity A is the cause of, or produces another fixed quantity B, is a proposition which, though convenient for scientific purposes, is apt to damage all inquiry, in so far as it leads us completely to ignore the innumerable conditions lying at the back of a phenomenon. It would, for instance, be an historical error to say that the dissolution of the Roman Empire was due to the barbarian invasions. The statement completely ignores other forces of a different character that tended to split up the political unity of the Empire. To describe the. advent of barbarian invasions as the cause of the dissolution of the Roman Empire which could have assimilated, as it actually did to, a certain extent, the so-called cause, is a procedure that no logic would justify. Let us, therefore, in the light of a truer theory of causation, enumerate the principal political, social, and intellectual conditions of Islamic life about the end of the 8th and the first half of the 9th century when, properly speaking, the Ṣūfī ideal of life came into existence, to be soon followed by a philosophical justification of that ideal.

(I). When we study the history of the time, we find it to be a time of more or less political unrest. The latter half of the 8th century presents, besides the political revolution which resulted in the overthrow of the Umayyads (749 A. D.), persecutions of Zendīks, and revolts of Persian heretics (Sindbāh 755--6; Ustādhīs 76.6-8; the veiled prophet of Khurāsān 777-80) who, working on the credulity of the people, cloaked, like Lamennais in our own times, political projects under the guise of religious ideas. Later on in the beginning of the 9th century we find the sons of Hārun (Ma'mun and Amīn) engaged in a terrible conflict for political supremacy; and still later, we see the Golden Age of Islamic literature seriously disturbed by the persistent revolt of the Mazdakite Bābak (816 - 838). The early years of Ma'mun's reign present another social phenomenon of great political significance - the 5hu'ubiyya controversy (815), which progresses with the rise and establishment of independent Persian families, the Tāhirīd (820), the Saffārīd (868), and the Sāmānīd Dynasty (874). It is, therefore, the combined force of these and other conditions of a similar nature that contributed to drive away spirits of devotional character from the scene of continual unrest to the blissful peace of an ever-deepening contemplative life. The semitic character of the life and thought of these early Muhammadan ascetics is gradually followed by a large hearted pantheism of a more or less Aryan stamp, the development of which, in fact, runs parallel to the slowly progressing political independence of Persia.

(2). The Sceptical tendencies of Islamic Rationalism which found an early expression in the poems of Bashshār ibn Burd - the blind Persian Sceptic who deified fire, and scoffed at all non-Persian modes of thought. The germs of Scepticism latent in Rationalism ultimately necessitated an appeal to a super-intellectual source of knowledge which asserted itself in the Risāla of Al-Qushairī (986). In our own times the negative results of Kant's Critique of Pure Reason drove Jacobi and Schleiermacher to base faith on the feeling of the reality of the ideal; and to the 19th century sceptic Wordsworth uncovered that mysterious state of mind “in which we grow all spirit and see into the life of things”.

(3). The unemotional piety of the various schools of Islam - the ῌanafite (Abu ῌanīfa d. 767), the Shāfiite (Al-Shāfi'ī d. 82o), the Mālikite (Al-Mālik d. 795), and the anthropomorphic ῌambalite (Ibn ῌambal d. 855) - the bitterest enemy of independent thought - which ruled the masses after the death of Al-Ma'mūn.

(4). The religious discussions among the representatives of various creeds encouraged by Al-Ma'mūn, and especially the bitter theological controversy between the Ash'arites and the advocates of Rationalism which tended not only to confine religion within the narrow limits of schools, but also stirred up the spirit to rise above all petty sectarian wrangling.

(5). The gradual softening of religious fervency due to the rationalistic tendency of the early ‘Abbāsid period, and the rapid growth of wealth which tended to produce moral laxity and indifference to religious life in the upper circles of Islam.

(6). The presence of Christianity as a working ideal of life. It was, however, principally the actual life of the Christian hermit rather than his religious ideas, that exercised the greatest fascination over the minds of early Islamic Saints whose complete unworldliness, though extremely charming in itself, is, I believe, quite contrary to the spirit of Islam.

Such was principally the environment of Ṣūfīism, and it is to the combined action of the above condition that we should look for the origin and development of Ṣūfiistic ideas. Given these conditions and the Persian mind with an almost innate tendency towards monism, the whole phenomenon of the birth and growth of Ṣūfīism is explained. If we now study the principal pre-existing conditions of Neo-Platonism, we find that similar conditions produced similar results. The barbarian raids which were soon to reduce Emperors of the Palace to Emperors of the Camp, assumed a more serious aspect about the middle of the third century. Plotinus himself speaks of the political unrest of his time in one of his letters to Flaccus.

When he looked round himself in Alexandria, his birth place, he noticed signs of growing toleration and indifferentism towards religious life. Later on in Rome which had become, so to say, a pantheon of different nations, he found a similar want of seriousness in life, a similar laxity of character in the upper classes of society. In more learned circles philosophy was studied as a branch of literature rather than for its own sake; and Sextus Empiricus, provoked by Antiochus's tendency to fuse scepticism and Stoicism was teaching the old unmixed scepticism of Pyrrho - that intellectual despair which drove Plotinus to find truth in a revelation above thought itself. Above all, the hard unsentimental character of Stoic morality, and the loving piety of the followers of Christ who, undaunted by long and fierce persecutions, were preaching the message of peace and love to the whole Roman world, necessitated a restatement of Pagan thought in a way that might revivify the older ideals of life, and suit the new spiritual requirements of the people. But the ethical force of Christianity was too great for Neo-Platonism which, on account of its more metaphysical.

character, had no message for the people at large, and was consequently inaccessible to the rude barbarian who, being influenced by the actual life of the persecuted Christian adopted Christianity, and settled down to construct new empires out of the ruins of the old. In Persia the influence of culture-contacts and cross-fertilisation of ideas created in certain minds a vague desire to realise a similar restatement of Islam, which gradually assimilated Christian ideals as well as Christian Gnostic speculation, and found a firm foundation in the Qur'ān. The flower of Greek Thought faded away before the breath of Christianity; but the burning simoon of Ibn Taimiyya's invective could not touch the freshness of the Persian rose. The one was completely swept away by the flood of barbarian invasions; the other, unaffected by the Tartar revolution, still holds its own.

This extraordinary vitality of the Ṣūfī restatemet of Islam, however, is explained when we reflect on the all-embracing structure of Ṣūfīism. The semitic formula of salvation can be briefly stated in the words, “Transform your will”, - which signifies that the Semite looks upon will as the essence of the human soul. The Indian Vedantist, on the other hand, teaches that all pain is due to our mistaken attitude towards the Universe. He, therefore, commands us to transform our understanding - implying thereby that the essential nature of man consists in thought, not activity or will. But the Ṣūfī holds that the mere transformation of will or understanding will not bring peace; we should bring about the transformation of both by a complete transformation of feeling, of which will and understanding are only specialised forms. His message to the individual is - “Love all, and forget your own individuality in doing good to others.” Says Rūmī:”To win other people's hearts is the greatest pilgrimage; and one heart is worth more than a thousand Ka'bāhs. Ka'bah is a mere cottage of Abraham; but the heart is the very home of God.” But this formula demands a why and a how - a metaphysical justification of the ideal in order to satisfy the understanding; and rules of action in order to guide the will. Ṣūfīism furnishes both. Semitic religion is a code of strict rules of conduct; the Indian Vedanta, on the other hand, is a cold system of thought. Ṣufīism avoids their incomplete Psychology, and attempts to synthesise both the Semitic and the Aryan formulas in the higher category of Love. On the one hand it assimilates the Buddhistic idea of Nirwāna (Fanā-Annihilation), and seeks to build a metaphysical system in the light of this idea; on the other hand it does not disconnect itself from Islam, and finds the justification of its view of the Universe in the Qur'ān. Like the geographical position of its home, it stands midway between the Semitic and the Aryan, assimilating ideas from both sides, and giving them the stamp of its own individuality which, on the whole, is more Aryan than Semitic in character. It would, therefore, be evident that the secret of the vitality of Ṣūfīism is the complete view of human nature upon which it is based. It has survived orthodox persecutions and political revolutions, because it appeals to human nature in its entirety; and, while it concentrates its interest chiefly in a life of self-denial, it allows free play to the speculative tendency as well.

I will now briefly indicate how Ṣūfī writers justify their views from. the Quranic standpoint. There is no historical evidence to show that the Prophet of Arabia actually communicated certain esoteric doctrines to 'Alī or Abū Bakr. The Ṣūfī, however, contends that the Prophet had an esoteric teaching - “wisdom” - as distinguished from the teaching contained in the Book, and he brings forward the following verse to substantiate his case - “As we have sent a prophet to you from among yourselves who reads our verses to you, purifies you, teaches you the Book and the wisdom, and teaches you what you did not know before.”

He holds that “the Wisdom” spoken of in the verse, is something not incorporated in the teaching of the Book which, as the prophet repeatedly declared, had been taught by several prophets before him. If, he says, the wisdom is included in the Book, the word “Wisdom” in the verse would be redundant. It can, I think, be easily shown that in the Qur'ān as well as in the authenticated traditions, there are germs of Ṣūfi doctrine which, owing to the thoroughly practical genius of the Arabs, could not develop and fructify in Arabia, but which grew up into a distinct doctrine when they found favourable circumstances in alien soils. The Qur'ān thus defines the Muslims:”Those who believe in the Unseen, establish daily prayer, and spend out of what We have given them.”

But the question arises as to the what and the where of the Unseen. The Qur'an replies that the Unseen is in your own soul - “And in the earth there are signs to those who believe, and in yourself, - what ! do you not then see!”

And again - “We are nigher to him (man) than his own jugular vein.”

Similarly the Holy Book teaches that the essential nature of the Unseen is pure light - “God is the light of heavens and earth.”

As regards the question whether this Primal Light is personal, the Qur'ān, in spite of many expressions signifying personality, declares in a few words - “There is nothing like him.”

These are some of the chief verses out of which the various Ṣūfī commentators develop pantheistic views of the Universe. They enumerate the following four stages of spiritual training through which the soul - the order or reason of the Primal Light - (“Say that the soul is the order or reason of God.”)

has to pass, if it desires to rise above the common herd, and realise its union or identity with the ultimate source of all things:

(1). Belief in the Unseen.

(2). Search after the Unseen. The spirit of inquiry leaves its slumber by observing the marvellous phenomena of nature. “Look at the camel how it is created; the skies how they are exalted; the mountains how they are unshakeably fixed.”

(3). The knowledge of the Unseen. This comes, as we have indicated above, by looking into the depths of our own soul.

(4). The Realisation - This results, according to the higher Ṣūfīism from the constant practice of Justice and Charity - “Verily God bids you do justice and good, and give to kindred (their due), and He forbids you to sin, and do wrong, and oppress”.

It must, however, be remembered that some later Ṣūfī fraternities (e.g. Naqshbandī) devised, or rather borrowed

from the Indian Vedantist,. other means of bringing about this Realisation. They taught, imitating the Hindu doctrine of Kundalīnī, that there are six great centres of light of various colours in the body of man. It is the object of the Ṣūfī to make them move, or to use the technical word, “current” by certain methods of meditation, and eventually to realise, amidst the apparent diversity of colours, the fundamental colourless light which makes everything visible, and is itself invisible. The continual movement of these centres of light through the body, and the final realisation of their identity, which results from putting the atoms of the body into definite courses of motion by slow repetition of the various names of God and other mysterious expressions, illuminates the whole body of the Ṣūfī; and the perception of the same illumination in the external world completely extinguishes the sense of “otherness.” The fact that these methods were known to the Persian Ṣūfīs misled Von Kremer who ascribed the whole phenomenon of Ṣūfīism to the influence of Vedantic ideas. Such methods. of contemplation are quite unislamic in character, and the higher Ṣūfīs do not attach any importance to them.

§ II. Aspects of Ṣūfī-Metaphysics

Let us now return to the various schools or rather the various aspects of Ṣūfī Metaphysics. A careful investigation of Ṣūfī literature shows that Ṣūfīism has looked at the Ultimate Reality from three standpoints which, in fact, do not exclude but complement each other. Some Ṣūfīs conceive the essential nature of reality as self-consious will, others beauty, others again hold that Reality is essentially Thought, Light or Knowledge. There are, therefore, three aspects of Ṣūfī thought:

A. Reality as Self-conscious Will

The first in historical order is that represented by Shaqīq Balkhī, Ibrāhim Adham, Rābi'a, and others. This school conceives the ultimate reality as “Will”, and the Universe a finite activity of that will. It is essentially monotheistic and consequently more semitic in character. It is not the desire of Knowledge which dominates the ideal of the Ṣūfīs of this school, but the characteristic features of their life are piety, unworldliness, and an intense longing for God due to the consciousness of sin. Their object is not to philosophise, but principally to work out a certain ideal of life. From our standpoint, therefore, they are not of much importance.

B. Reality as Beauty

In the beginning of the 9th century Ma'rūf Karkhī defined Ṣūfīism as “Apprehension of Divine realities”{13] - a definition which marks the movement from Faith to Knowledge. But the method of apprehending the ultimate reality was formally stated by Al-Oushairī about the end of the 10th century. The teachers of this school adopted the Neo-Platonic idea of creation by intermediary agencies; and though this idea lingered in the minds of Ṣūfī writers for a long time, yet their Pantheism led them to abandon the Emanation theory altogether. Like Avicenna they looked upon the ultimate Reality as “Eternal Beauty” whose very nature consists in seeing its own “face” reflected in the Universe-mirror. The Universe, therefore, became to them a reflected image of the “Eternal Beauty”, and not an emanation as the Neo-Platonists had taught. The cause of creation, says Mīr Sayyid Sharīf, is the manifestation of Beauty, and the first creation is Love. The realisation of this Beauty, is brought about by universal love, which the innate Zoroastrian instinct of the Persian Ṣūfi loved to define as “the Sacred Fire which burns up everything other than God.” Says Rūmī:

“O thou pleasant madness, Love!

Thou Physician of all our ills!

Thou healer of pride,

Thou Plato and Galen of our souls!”

As a direct consequence of such a view of the Universe, we have the idea of impersonal absorption which first appears in Bāyazīd of Bistām, and which constitutes the characteristic: feature of the later development of this school.. The growth of this idea may have been influenced by Hindu pilgrims travelling through Persia to the Buddhistic temple still existing-at Bāku.

The school became wildly pantheistic in Husain Manṣūr who, in the true spirit of the Indian Vedantist, cried out, “I am God” - Aham Brahma asmi.

The ultimate Reality or Eternal Beauty, according to the Ṣūfīs of this school, is infinite in the sense that “it is absolutely free from the limitations of beginning, end, right, left, above, and below.”

The distinction of essence and attribute does not exist in the Infinite - “Substance and quality are really identical.”

We have indicated above that nature is the mirror of the Absolute Existence. But according to Nasafī, there are two kinds of mirrors:

(a). That which shows merely a reflected image - this is external nature.

(b). That which shows the real Essence - this is man who is a limitation of the Absolute, and erroneously thinks himself to be an independent entity.

“O Derwish !” says Nasafī “dost thou think that thy existence is independent of God ? This is a great error.”

Nasafī explains his meaning by a beautiful parable.

The fishes in a certain tank realised that they lived, moved, and had their being in water, but felt that they were quite ignorant of the real nature of what constituted the very source of their life. They resorted to a wiser fish in a great river, and the Philosopher-fish addressed them thus:

“O you who endeavour to untie the knot (of being) ! You are born in union, yet die in the thought of an unreal separation. Thirsty on the sea-shore ! Dying penniless while master of the treasure !”

All feeling of separation, therefore, is ignorance; and all “otherness” is a mere appearance, a dream, a shadow - a differentiation born of relation essential to the self-recognition of the Absolute. The great prophet of this school is “The excellent Rūlmī” as Hegel calls him. He took up the old Neo-Platonic idea of the Universal soul working through the various spheres of being, and expressed it in a way so modern in spirit that Clodd introduces the passage in his “Story of Creation”. I venture to quote this famous passage in order to show how successfully the poet anticipates the modern concept of evolution, which he regarded as the realistic side of his Idealism.

First man appeared in the class of inorganic things,

Next he passed therefrom into that of plants.

For years he lived as one of the plants,

Remembering nought of his inorganic state so different;

And when he passed from the vegetive to the animal state,

He had no remembrance of his state as a plant,

Except the inclination he felt to the world of plants,

Especially at the time of spring and sweet flowers;

Like the inclination of infants towards their mothers,

Which know not the cause of their inclination to the breast.

Again the great creator as you know,

Drew man out of the animal into the human state.

Thus man passed from one order of nature to another,

Till he became wise and knowing and strong as he is now.

Of his first soul he has now no remembrance,

And he will be again changed from his present soul.

(Mathnawī Book IV).

It would now be instructive if we compare this aspect of Ṣūfī thought with the fundamental ideas of Neo-Platonism. The God of Neo-Platonism is immanent as well as transcendant. “As being the cause of all things, it is every-where. As being other than all things, it is nowhere. If it were only “everywhere”, and not also “nowhere”, it would beall things.

The Ṣūfī, however, tersely says that God is all things. The Neo-Platonist allows a certain permanence or fixity to matter;

but the Ṣūfīs of the school in question, regard all empirical experience as a kind of dreaming. Life in limitation, they say, is sleep; death brings the awakening. It is, however, the doctrine of Impersonal immortality - “genuinely eastern in spirit” - which distinguishes this school from Neo-Platonism. “Its (Arabian Philosophy) distinctive doctrine”, says Whittaker, “of an Impersonal immortality of the general human intellect is, however, as contrasted with Aristotelianism and Neo-Platonism, essentially original.”

The above brief exposition shows that there are three basic ideas of this mode of thought:

(a). That the ultimate Reality is knowable through a supersensual state of consciousness.

(b). That the ultimate Reality is impersonal.

(c). That the ultimate Reality is one. Corresponding to these ideas we have:

(I). The Agnostic reaction as manifested in the Poet 'Umar Khayyām (12th century) who cried out in his intellectual despair:

The joyous souls who quaff potations deep, And saints who in the mosque sad vigils keep, Are lost at sea alike, and find no shore, One only wakes, all others are asleep.

(II). The monotheistic reaction of Ibn Taimiyya and his followers in the 13th century.

(III). The Pluralistic reaction of Wāḥid Maḥmūd

in the 13th century.

Speaking from a purely philosophical stand-point, the last movement is most interesting. The history of Thought illustrates the operation of certain general laws of progress which are true of the intellectual annals of different peoples. The German systems of monistic thought invoked the pluralism of Herbart; while the pantheism of Spinoza called forth the monadism of Leibniz. The operation of the same law led Wāhid Mahmūd to deny the truth of contemporary monism, and declare that Reality is not one, but many. Long before Leibniz he taught that the Universe is a combination of what he called “Afrād” - essential units, or simple atoms which have existed from all eternity, and are endowed with life. The law of the Universe is an ascending perfection of elemental matter, continually passing from lower to higher forms determined by the kind of food which the fundamental units assimilate. Each period of his cosmogony comprises 8,000 years, and after eight such periods the world is decomposed, and the units re-combine to construct a new universe. Wāḥid Maḥmūd succeeded in founding a sect which was cruelly persecuted, and finally stamped out of existence by Shāh 'Abbās. It is said that the poet ῌāfiz of Shīrāz believed in the tenets of this sect.

C. Reality as Light or Thought

The third great school of Ṣūfīism conceives Reality as essentially Light or Thought, the very nature of which demands something to be thought or illuminated. While the preceding school abandoned Neo-Platonism, this school transformed it into new systems. There are, however, two aspects of the metaphysics of this school. The one is genuinely Persian in spirit, the other is chiefly influenced by Christian modes of thought. Both agree in holding that the fact of empirical diversity necessitates a principle of difference in the nature of the ultimate Reality. I now proceed to consider them in their historical order.

I. Reality as Light - Al-Ishrāqī

Return to Persian Dualism.

The application of Greek dialectic to Islamic Theology aroused that spirit of critical examination which began with Al-Ash'arī, and found its completest expression in the scepticism of Al-Ghazālī. Even among the Rationalists there were some more critical minds - such as Nazzām - whose attitude towards Greek Philosophy was not one of servile submission, but of independent criticism. The defenders of dogma - Al-Ghazālī, Al-Rāzī, Abul Barakāt, and Al-Āmidī, carried on a persistent attack on the whole fabric of Greek Philosophy; while Abu Sa'īd Ṣairāfī, Qaḍī ‘Abdal Jabbār, Abul Ma'ālī, Abul Qāsim, and finally the acute Ibn Taimiyya, actuated by similar theological motives, continued to expose the inherent weakness of Greek Logic. In their criticism of Greek Philosophy, these thinkers were supplemented by some of the more learned Ṣūfīs, such as Shahābal Dīn Suhrawardī, who endeavoured to substantiate the helplessness of pure reason by his refutation of Greek thought in a work entitled, “The unveiling of Greek absurdities”. The Ash'arite reaction against Rationalism resulted not only in the development of a system of metaphysics most modern in some of its aspects, but also in completely breaking asunder the worn out fetters of intellectual thraldom. Erdmann

seems to think that the speculative spirit among the Muslims exhausted itself with Al-Fārābī and Avicenna, and that after them Philosophy became bankrupt in passing over into scepticism and mysticism. Evidently he ignores the Muslim criticism of Greek Philosophy which led to the Ash'arite Idealism on the one hand, and a genuine Persian reconstruction on the other. That a system of thoroughly Persian character might be possible, the destruction of foreign thought, or rather the weakening of its hold on the mind, was indispensable. The Ash'arite and other defenders of Islamic Dogma completed the destruction; Al-Ishrāqī - the child of emancipation - came forward to build a new edifice of thought; though, in his process of reconstruction, he did not entirely repudiate the older material. His is the genuine Persian brain which, undaunted by the threats of narrow minded authority, asserts its right of free independent speculation. In his philosophy the old Iranian tradition, which had found only a partial expression in the writings of the Physician Al-Rāzī, Al-Ghazālī, and the Ismailia sect, endeavours to come to a final understanding with the philosophy of his precessors and the theology of Islam.

Shaikh Shahābal Dīn Suhrawardī, known as Shaikhal Ishrāq Maqtūl was born about the middle of the 12th century. He studied philosophy with Majd Jīlī - the teacher of the commentator Al-Rāzī - and, while still a youth, stood unrivalled as a thinker in the whole Islamic world. His great admirer Al-Malik-al-Zāhir - the son of Sultan Ṣalāḥ-al Dīn - invited him to Aleppo, where the youthful philosopher expounded his independent opinions in a way that aroused the bitter jealousy of contemporary theologians. These hired slaves of bloodthirsty Dogmatism which, conscious of its inherent weakness, has always managed to keep brute force behind its back, wrote to Sultan Ṣalāḥ-al Dīn, that the Shaikh's teaching was a danger to Islam, and that it was necessary, in the interest of the Faith, to nip the evil in the bud. The Sultan consented; and there, at the early age of 36, the young Persian thinker calmly met the blow which made him a martyr of truth, and immortalised his name for ever. Murderers have passed away, but the philosophy, the price of which was paid in blood, still lives, and attracts many an earnest seeker after truth.

The principal features of the founder of the Ishrāqī Philosophy are his intellectual independence, the skill with which he weaves his materials into a systematic whole, and above all his faithfulness to the philosophic traditions of his country. In many fundamental points he differs from Plato, and freely criticises Aristotle whose philosophy he looks upon as a mere preparation for his own system of thought. Nothing escapes his criticism. Even the logic of Aristotle, he subjects to a searching examination, and shows the hollowness of some of its doctrines. Definition, for instance, is genus plus differentia, according to Aristotle. But Al-Ishrāqī holds that the distinctive attribute of the thing defined, which cannot be predicated of any other thing, will bring us no knowledge of the thing. We define “horse” as a neighing animal. Now we understand animality, because we know many animals in which this attribute exists; but it is impossible to understand the attribute “neighing”, since it is found nowhere except in the thing defined. The ordinary definition of horse, therefore, would be meaningless to a man who has never seen a horse. Aristotelian definition, as a scientific principle is quite useless. This criticism leads the Shaikh to a standpoint very similar to that of Bosanquet who defines definition, as “Summation of qualities”. The Shaikh holds that a true definition would enumerate all the essential attributes which, taken collectively, exist nowhere except the thing defined, though they may individually exist in other things.

But let us turn to his system of metaphysics, and estimate the worth of his contribution to the thought of his country. In order fully to comprehend the purely intellectual side of Transcendental philosophy, the student, says the Shaikh, must be thoroughly acquainted with Aristotelian philosophy, Logic, Mathematics, and Ṣūfīism. His mind should be completely free from the taint of prejudice and sin, so that he may gradually develop that inner sense, which verifies and corrects what intellect understands only as theory. Unaided reason is untrustworthy; it must always be supplemented by “Dhauq” - the mysterious perception of the essence of things - which brings know-ledge and peace to the restless soul, and disarms Scepticism for ever. We are, however, concerned with the purely speculative side of this spiritual experience - the results of the inner perception as formulated and systematised by discursive thought. Let us, therefore, examine the various aspects of the Ishrāqī Philosophy - Ontology, Cosmology, and Psychology.

Ontology

The ultimate principle of all existence is “Nūr-i-Qāhir” - the Primal Absolute Light whose essential nature consists in perpetual illumination. “Nothing is more visible than light, and visibility does not stand in need of any definition.”

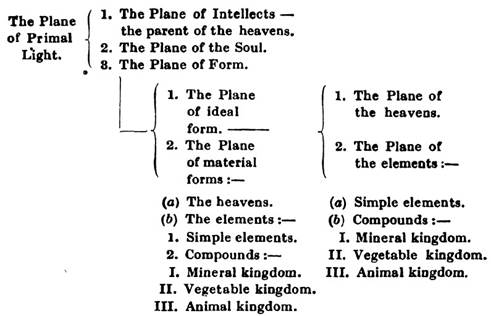

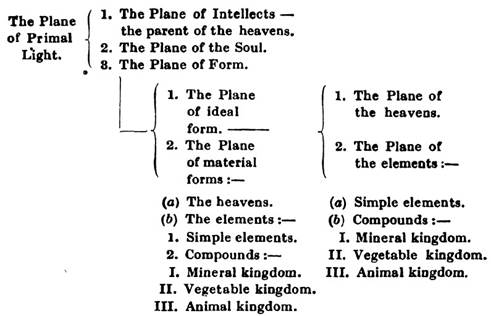

The essence of Light, there-fore, is manifestation. For if manifestation is an attribute superadded to light, it would follow that in itself light possesses no visibility, and becomes visibile only through something else visible in itself; and from this again follows the absurd consequence, that something other than light is more visible than light. The Primal Light, therefore, has no reason of its existence beyond itself. All that is other than this original principle is dependent, contingent, possible. The “not-light” (darkness) is not something distinct proceeding from an independent source. It is an error of the representatives of the Magian religion to suppose that Light and Darkness are two distinct realities created by two distinct creative agencies. The ancient Philosophers of Persia were not dualists like the Zoroastrian priests who, on the ground of the principle that the one cannot cause to emanate from itself more than one, assigned two independent sources to Light and Darkness. The relation between them is not that of contrariety, but of existence and non-existence. The affirmation of Light necessarily posits its own negation - Darkness which it must illuminate in order to be itself. This Primordial Light is the source of all motion. But its motion is not change of place; it is due to the love of illumination which constitutes its very essence, and stirs it up, as it were, to quicken all things into life, by pouring out its own rays into their being. The number of illuminations which proceed from it is infinite. Illuminations of intenser brightness become, in their turn, the sources of other illuminations; and the scale of brightness gradually descends to illuminations too faint to beget other illuminations. All these illuminations are mediums, or in the language of Theology, angels through whom the infinite varieties of being receive life and sustenance from the Primal Light. The followers of Aristotle erroneously restricted the number of original Intellects to ten. They likewise erred in enumerating the categories of thought. The possibilities of the Primal Light are infinite; and the Universe, with all its variety, is only a partial expression of the infinitude behind it. The categories of Aristotle, therefore, are only relatively true. It is impossible for human thought to comprehend within its tiny grasp, all the infinite variety of ideas according to which the Primal Light does or may illuminate that which is not light. We can, however, discriminate between the following two illuminations of the original Light:

(1). The Abstract Light (e. g. Intellect Universal as well as individual). It has no form, and never becomes the attribute of anything other than itself (Substance). From it proceed all the various forms of partly-conscious, conscious, or self-conscious light, differing from one another in the amount of lustre, which is,determined by their comparative nearness or distance from the ultimate source of their being_ The individual intellect or soul is only a fainter copy, or a more distant reflection of the Primal Light. The Abstract Light knows itself through itself, and does not stand in need of a non-ego to reveal its own existence to itself. Consciousness or self-knowledge, therefore, is the very essense. of Abstract light, as distinguished from the negation of light.

(2). The Accidental light (Attribute) - the light that has a form, and is capable of becoming an attribute of something other than itself (e.g. the light of the stars, or the visibility of other bodies). The Accidental light, or more properly sensible light, is a distant reflection of the Abstract light, which, because of its distance, has lost the intensity, or substance-character of its parent. The process of continuous reflection is really a softening process; successive illuminations gradually lose their intensity until, in the chain of reflections, we reach certain less intense illuminations which entirely lose their independent character, and cannot exist except in association with something else. These illuminations form the Accidental light - the attribute which has no independent existence. The relation, therefore, between the Accidental and the Abstract light is that of cause and effect. The effect, however, is not something quite distinct from its cause; it is a transformation, or a weaker form of the supposed cause itself. Anything other than the Abstract light (e. g. the nature of the illuminated body itself) cannot be the cause of the Accidental light; since the latter, being merely contingent and consequently capable of being negatived, can be taken away from bodies, without affecting their character. If the essence or nature of the illuminated body, had been the cause of the Accidental light, such a process of disillumination could not have been possible. We cannot conceive an inactive cause.

It is now obvious that the Shaikh al-Ishrāq agrees with the Ash'arite thinkers in holding that there is no such thing as the Prima Materia of Aristotle; though he recognises the existence of a necessary negation of Light - darkness, the object of illumination. He further agrees with them in teaching the relativity of all categories except Substance and Quality. But he corrects their theory of knowledge, in so far as he recognises an active element in human knowledge. Our relation with the objects of our knowledge is not merely a passive relation; the individual soul, being itself an illumination, illuminates the object in the act of knowledge. The Universe to him is one great process of active illumination; but, from a purely intellectual standpoint, this illumination is only a partial expression of the infinitude of the Primal Light, which may illuminate according to other laws not known to us. The categories of thought are infinite; our intellect works with a few only. The Shaikh, therefore, from the standpoint of discursive thought, is not far from modern Humanism.

Cosmology

All that is “not-light” is, what the Ishrāqī thinkers call, “Absolute quantity”, or “Absolute matter”. It is only another aspect of the affirmation of light, and not an independent principle, as the followers of Aristotle erroneously hold. The experimental fact of the transformation of the primary elements into one another, points to this fundamental Absolute matter which, with its various degrees of grossness, constitutes the various spheres of material being. The absolute ground of all things, then, is divided into two kinds:

(1). That which is beyond space - the obscure substance or atoms (essences of the Ash'arite).

(2). That which is necessarily in space - forms of darkness, e. g. weight, smell, taste, etc.

The combination of these two particularises the Absolute matter. A material body is forms of darkness plus obscure substance, made visible or illuminated by the Abstract light. But what is the cause of the various forms of darkness? These, like the forms of light, owe their existence to the Abstract light, the different illuminations of which cause diversity in the spheres of being. The forms which make bodies differ from one another, do not exist in the nature of the Absolute matter. The Absolute quantity and the Absolute matter being identical, if these forms do exist in the essence of the Absolute matter, all bodies would be identical in regard to the forms of darkness. This, however, is contradicted by daily experience. The cause of the forms of darkness, therefore, is not the Absolute matter. And as the difference of forms cannot be assigned to any other cause, it follows that they are due to the various illuminations of the Abstract light. Forms of light and darkness both owe their existence to the Abstract Light. The third element of a material body - the obscure atom or essence - is nothing but a necessary aspect of the affirmation of light. The body as a whole, therefore, is completely dependent on the Primal Light. The whole Universe is really a continuous series of circles of existence, all depending on the original Light. Those nearer to the source receive more illumination than those more distant. All varieties of existence in each circle, and the circles themselves, are illuminated through an infinite number of medium-illuminations, which preserve some forms of existence by the help of “conscious light” (as in the case of man, animal and plant), and some without it (as in the case of minerals and primary elements). The immense panorama of diversity which we call the Universe, is, therefore, a vast shadow of the infinite variety in intensity of direct or indirect illuminations and rays of the Primary Light. Things are, so to speak, fed by their respective illuminations to which they constantly move, with a lover's passion, in order to drink more and more of the original fountain of Light. The world is an eternal drama of love. The different planes of being are as follow:

Having briefly indicated the general nature of Being, we now proceed to a more detailed examination of the world-process. All that is not-light is divided into:

(1). Eternal e. g., Intellects, Souls of heavenly bodies, heavens, simple elements, time, motion.

(2). Contingent e.g., Compounds of various elements. The motion of the heavens is eternal, and makes up the various cycles of the Universe. It is due to the intense longing of the heaven-soul to receive illumination from the source of all light. The matter of which the heavens are constructed, is completely free from the operation of chemical processes, incidental to the grosser forms of the not-light. Every heaven has its own matter peculiar to it alone. Likewise the heavens differ from one another in the direction of their motion; and the difference is explained by the fact that the beloved, or the sustaining illumination, is different in each case. Motion is only an aspect of time. It is the summing up of the elements of time, which, as externalised, is motion, The distinction of past, present, and future is made only for the sake of convenience, and does not exist in the

nature of time.

We cannot conceive the beginning of time; for the supposed beginning would be a point of time itself. Time and motion, therefore, are both eternal.

There are three primordial elements - water, earth, and wind. Fire, according to the Ishrāqīs, is only burning wind. The combinations of these elements, under various heavenly influences, assume various forms - fluidity, gaseousness, solidity. This transformation of the original elements, constitutes the process of “making and unmaking” which pervades the entire sphere of the not-light, raising the different forms of existence higher and higher, and bringing them nearer and nearer to the illuminating forces. All the phenomena of nature - rain, clouds, thunder, meteor - are the various workings of this immanent principle of motion, and are explained by the direct or indirect operation of the Primal Light on things, which differ from one another in their capacity of receiving more or less illumination. The Universe, in one word, is a petrified desire; a crystallised longing after light.

But is it eternal? The Universe is a manifestation of the illuminative Power which constitutes the essential nature of the Primal Light. In so far, therefore, as it is a manifestation, it is only a dependent being, and consequently not eternal. But in another sense it is eternal. All the different spheres of being exist by the illuminations and rays of the Eternal light. There are some illuminations which are directly eternal; while there are other fainter ones, the appearance of which depends on the combination of other illuminations and rays. The existence of these is not eternal in the same sense as the existence of the pre-existing parent illuminations. The existence of colour, for instance, is contingent in comparison to that of the ray, which manifests colour when a dark body is brought before an illuminating body. The Universe, therefore, though contingent as manifestation, is eternal by the eternal character of its source. Those who hold the non-eternity of the Universe argue on the assumption of the possibility of a complete induction. Their argument proceeds in the following manner:

(1). Everyone of the Abyssinians is black.

All Abyssinians are black.

(2). Every motion began at a definite moment.

All motion must begin so.

But this mode of argumentation is vicious. It is quite impossible to state the major. One cannot collect all the Abyssinians past, present, and future, at one particular moment of time. Such a Universal, therefore, is impossible. Hence from the examination of individual Abyssinians, or particular instances of motion which fall within the pale of our experience, it is rash to infer, that all Abyssinians are black, or all motion had a beginning in time.

Psychology

Motion and light are not concomitant in the case of bodies of a lower order. A piece of stone, for instance, though illuminated and hence visible, is not endowed with self-initiated movement. As we rise, however, in the scale of being, we find higher bodies, or organisms in which motion and light are associated together. The abstract illumination finds its best dwelling place in man. But the question arises whether the individual abstract illumination which we call the human soul, did or did not exist before its physical accompaniment. The founder of Ishrāqī Philosophy follows Avicenna in connection with this question, and uses the same arguments to show, that the individual abstract illuminations cannot be held to have pre-existed, as so many units of light. The material categories of one and many cannot be applied to the abstract illumination which, in its essential nature, is neither one nor many; though it appears as many owing to the various degrees of illuminational receptivity in its material accompaniments. The relation between the abstract illumination, or soul and body, is not that of cause and effect; the bond of union between them is love. The body which longs for illumination, receives it through the soul; since its nature does not permit a direct communication between the source of light and itself. But the soul cannot transmit the directly received light to the dark solid body which, considering its attributes, stands on the opposite pole of being. In order to be related to each other, they require a medium between them, something standing midway between light and darkness. This medium is the animal soul - a hot, fine, transparent vapour which has its principal seat in the left cavity of the heart, but also circulates in all parts of the body. It is because of the partial identity of the animal soul with light that, in dark nights, land-animals run towards the burning fire; while sea-animals leave their aquatic abodes in order to enjoy the beautiful sight of the moon. The ideal of man, therefore, is to rise higher and higher in the scale of being, and to receive more and more illumination which gradually brings complete freedom from the world of forms. But how is this ideal to be realised? By knowledge and action. It is the transformation of both understanding and will, the union of action and contemplation, that actualises the highest ideal of man. Change your attitude towards the Universe, and adopt the line of conduct necessitated by the change. Let us briefly consider these means of realisation:

A. Knowledge. When the Abstract illumination associates itself with a higher organism, it works out its development by the operation of certain faculties - the powers of light, and the powers of darkness. The former are the five external senses, and the five internal senses - sensorium, conception, imagination, understanding, and memory; the latter are the powers of growth, digestion, etc. But such a division of faculties is only convenient. “One faculty can be the source of all operations.”

There is only one power in the middle of the brain, though it receives different names from different standpoints. The mind is a unity which, for the sake of convenience, is regarded as multiplicity. The power residing in the middle of the brain must be distinguished from the abstract illumination which constitutes the real essence of man. The Philosopher of illumination appears to draw a distinction between the active mind and the essentially inactive soul; yet he teaches that in some mysterious way, all the various faculties are connected with the soul.

The most original point in his psychology of intellection, however, is his theory of vision.

The ray of light which is supposed to come out of the eye must be either substance or quality. If quality, it cannot be transmitted from one substance (eye) to another substance (visible body). If, on the other hand, it is a substance, it moves either consciously, or impelled by its inherent nature. Conscious movement would make it an animal perceiving other things. The perceiver in this case would be the ray, not man. If the movement of the ray is an attribute of its nature, there is no reason why its movement should be peculiar to one direction, and not to all. The ray of light, therefore, cannot be regarded as coming out of the eye. The followers of Aristotle hold that in the process of vision images of objects are printed on the eye. This view is also erroneous; since images of big things cannot be printed on a small space. The truth is that when a thing comes before the eye, an illumination takes place, and the mind sees the object through that illumination. When there is no veil between the object and the normal sight, and the mind is ready to perceive, the act of vision must take place; since this is the law of things. “All vision is illumination; and we see things in God”. Berkley explained the relativity of our sight-perceptions with a view to show that the ultimate ground of all ideas is God. The Ishrāqī Philosopher has the same object in view, though his theory of vision is not so much an explanation of the sight-process as a new way of looking at the fact of vision.

Besides sense and reason, however, there is another source of knowledge called “Dhauq” - the inner perception which reveals non-temporal and non-spatial planes of being. The study of philosophy, or the habit of reflecting on pure concepts, combined with the practice of virtue, leads to the upbringing of this mysterious sense, which corroborates and corrects the conclusions of intellect.

B. Action. Man as an active being has the following motive powers:

(a). Reason or the Angelic soul - the source of intelligence, discrimination, and love of knowledge.

(b). The beast-soul which is the source of anger, courage, dominance, and ambition.

(c). The animal soul which is the source of lust, hunger, and sexual passion.

The first leads to wisdom; the second and third, if controlled by reason, lead respectively to bravery and chastity. The harmonious use of all results in the virtue of justice. The possibility of spiritual progress by virtue, shows that this world is the best possible world. Things as existent are neither good nor bad. It is misuse or limited standpoint that makes them so. Still the fact of evil cannot be denied. Evil does exist; but it is far less in amount than good. It is peculiar only to a part of the world of darkness; while there are other parts of the Universe which are quite free from the taint of evil. The sceptic who attributes the existence of evil to the creative agency of God, presupposes resemblance between human and divine action, and does not see that nothing existent is free in his sense of the word. Divine activity cannot be regarded as the creator of evil in the same sense as we regard some forms of human activity as the cause of evil.

It is, then, by the union of knowledge and virtue that the soul frees itself from the world of darkness. As we know more and more of the nature of things, we are brought closer and closer to the world of light; and the love of that world becomes more and more intense. The stages of spiritual development are infinite, since the degrees of love are infinite. The principal stages, however, are as follows:

(1). The stage of “I”. In this stage the feeling of personality is most predominant, and the spring of human action is generally selfishness.

(2). The stage of “Thou art not”. Complete absorption in one's own deep self to the entire forgetfulness of everything external.

(3). The stage of “I am not”. This stage is the necessary result of the second.

(4.). The stage of “ Thou art”. The absolute negation of “I”, and the affirmation of “ Thou”, which means complete resignation to the will of God.

(5). The stage of “I am not; and thou art not”. The complete negation of both the terms of thought - the state of cosmic consciousness.

Each stage is marked by more or less intense illuminations, which are accompanied by some indescribable sounds. Death does not put an end to the spiritual progress of the soul. The individual souls, after death, are not unified into one soul, but continue different from each other in proportion to the illumination they received during their companionship with physical organisms. The Philosopher of illumination anticipates Leibniz's doctrine of the Identity of Indiscernibles, and holds that no two souls can be completely similar to each other.

When the material machinery which it adopts for the purpose of acquiring gradual illumination, is exhausted, the soul probably takes up another body determined by the experiences of the previous life; and rises higher and higher in the different spheres of being, adopting forms peculiar to those spheres, until it reaches its destination - the state of absolute negation. Some souls probably come back to this world in order to make up their deficiencies.

The doctrine of trans-migration cannot be proved or disproved from a purely logical standpoint; though it is a probable hypothesis to account for the future destiny of the soul. All souls are thus constantly journeying towards their common source, which calls back the whole Universe when this journey is over, and starts another cycle of being to reproduce, in almost all respects, the history of the preceding cycles.

Such is the philosophy of the great Persian martyr. He is, properly speaking, the first Persian systematiser who recognises the elements of truth in all the aspects of Persian speculation, and skilfully synthesises them in his own system. He is a pantheist in so far as he defines God as the sum total of all sensible and ideal existence.

To him, unlike some of his Ṣūfī predecessors, the world is something real, and the human soul a distinct individuality. With the orthodox theologian, he mantains that the ultimate cause of every phenomenon, is the absolute light whose illumination forms the very essence of the

Universe. In his psychology he follows Avicenna, but his treatment of this branch of study is more systematic and more empirical. As an ethical philosopher, he is a follower of Aristotle whose doctrine of the mean he explains and illustrates with great thoroughness. Above all he modifies and transforms the traditional Neo-Platonism, into a thoroughly Persian system of thought which, not only approaches Plato, but also spiritualises the old Persian Dualism. No Persian thinker is more alive to the necessity of explaining all the aspects of objective existence in reference to his fundamental principles. He constantly appeals to experience, and endeavours to explain even the physical phenomena in the light of his theory of illumination. In his system objectivity, which was completely swallowed up by the exceedingly subjective character of extreme pantheism, claims its due again, and, having been subjected to a detailed examination, finds a comprehensive explanation. No wonder then that this acute thinker succeeded in founding a system of thought, which has always exercised the greatest fascination over minds - uniting speculation and emotion in perfect harmony. The narrowmindedness of his con-temporaries gave him the title of “Maqtūl” (the killed one), signifying that he was not to be regarded as “Shahid” (Martyr); but succeeding generations of Sufis and philosophers have always given him the profoundest veneration.

I may here notice a less spiritual form of the Ishrāēqī mode of thought. Nasafī

describes a phase of Sufi thought which reverted to the old materialistic dualism of Mani. The advocates of this view hold, that light and darkness are essential to each other. They are, in reality, two rivers which mix with each other like oil and milk,

out of which arises the diversity of things. The ideal of human action is freedom from the taint of darkness; and the freedom of light from darkness means the self-consciousness of light as light.

II. Reality as Thought - Al-Jīlī

Al-Jīlī was born in 767 A.H., as he himself says in one of his verses, and died in 811 A.H. He was not a prolific writer like Shaikh Muḥy al-Din ibn 'Arabī whose mode of thought seems to have greatly influenced his teaching. He combined in himself poetical imagination and philosophical genius, but his poetry is no more than a vehicle for his mystical and metaphysical doctrines. Among other books he wrote a commentary on Shaikh Muby al-Din ibn 'Arabī's al-Futūḥat al-Makkiya, a commentary on Bismillāh, and the famous work Insān al-Kāmil (printed in Cairo).

Essence pure and simple, he says, is the thing to which names and attributes are given, whether it is existent actually or ideally. The existent is of two species:

(1). The Existent in Absoluteness or Pure existence - Pure Being - God.

(2). The existence joined with non-existence - Creation - Nature.

The Essence of God or Pure Thought cannot be understood; no words can express it, for it is beyond all relation and knowledge is relation. The intellect flying through the fathomless empty space pierces through the veil of names and attributes, traverses the vasty sphere of time, enters the domain of the non-existent and finds the Essence of Pure Thought to be an existence which is non-existence - a sum of contradictions.

It has two (accidents); eternal life in all past time and eternal life in all future time. It has two (qualities), God and creation. It has two (definitions), uncreatableness and creatableness. It has two names, God and man. It has two faces, the manifested (this world) and the unmanifested (the next world). It has two effects, necessity and possibility. It has two points of view; from the first it is non-existent for itself but existent for what is not itself; from the second it is existent for itself and non-existent for what is not itself.

Name, he says, fixes the named in the understanding, pictures it in the mind, presents it in the imagination and keeps it in the memory. It is the outside or the husk, as it were, of the named; while the named is the inside or the pith. Some names do not exist in reality but exist in name only as “'Anqā” (a fabulous bird). It is a name the object of which does not exist in reality. Just as “'Anqā” is absolutely non-existent, so God is absolutely present, although He cannot be touched and seen. The “'Anqā” exists only in idea while the object of the name “Allah” exists in reality and can be known like “'Anqā” only through its names and attributes. The name is a mirror which reveals all the secrets of the Absolute Being; it is a light through the agency of which God sees Himself. AI-Jīlī here approaches the Ismailia view that we should seek the Named through the Name.

In order to understand this passage we should bear in mind the three stages of the development of Pure Being, enumerated by him. He holds that the Absolute existence or Pure Being when it leaves its absoluteness undergoes three stages:(I) Oneness. (2) an He-ness. (3) I-ness. In the first stage there is an absence of all attributes and relations, yet it is called one, and therefore oneness marks one step away from the absoluteness. In the second stage Pure Being is yet free from all manifestation, while the third stage, I-ness, is nothing but an external manifestation of the He-ness; or, as Hegel would say, it is the self-diremption of God. This third stage is the sphere of the name Allāh; here the darkness of Pure Being is illuminated, nature comes to the front, the Absolute Being has become conscious. He says further that the name Allāh is the stuff of all the perfections of the different phases of Divinity, and in the second stage of the progress of Pure Being, all that is the result of Divine self-diremption was potentially contained within the titanic grasp of this name which, in the third stage of the development, objectified itself, became a mirror in which God reflected Himself, and thus by its crystallisation dispelled all the gloom of the Absolute Being.

In correspondence with these three stages of the absolute development, the perfect man has three stages of spiritual training. But in his case the process of development must be the reverse; because his is the process of ascent, while the Absolute Being had undergone essentially a process of descent. In the first stage of his spiritual progress he meditates on the name, studies nature on which it is sealed; in the second stage he steps into the sphere of the Attribute, and in the third stage enters the sphere of the Essence. It is here that he becomes the Perfect Man; his eye becomes the eye of God, his word the word of God and his life the life of God - participates in the general life of Nature and “sees into the life of things”.

To turn now to the nature of the attribute. His views on this most interesting question are very important, because it is here that his doctrine fundamentally differs from Hindu Idealism. He defines attribute as an agency which gives us a knowledge of the state of things.

Elsewhere he says that this distinction of attribute from the underlying reality is tenable only in the sphere of the manifested, because here every attribute is regarded as the other of the reality in which it is supposed to inhere. This otherness is due to the existence of combination and disintegration in the sphere of the manifested. But the distinction is untenable in the domain of the unmanifested, because there is no combination or disintegration there. It should be observed how widely he differs from the advocates of the Doctrine of “Māyā”. He believes that the material world has real existence; it is the outward husk of the real being, no doubt, but this outward husk is not the less real. The cause of the phenomenal world, according to him, is not a real entity hidden behind the sum of attributes, but it is a conception furnished by the mind so that there may be no difficulty in understanding the material world. Berkeley and Fichte will so far agree with our author, but his view leads him to the most characteristically Hegelian doctrine - identity of thought and being. In the 37th chapter of the 2nd volume of Insān al-Kāmil, he clearly says that idea is the stuff of which this universe is made; thought, idea, notion is the material of the structure of nature. While laying stress on this doctrine he says, “Dost thou not look to thine own belief? Where is the reality in which the so-called Divine attributes inhere? It is but the idea.”

Hence nature is nothing but a crystallised idea. He gives his hearty assent to the results of Kant's Critique of Pure Reason; but, unlike him, he makes this very idea the essence of the Universe. Kant's Ding an sick to him is a pure nonentity; there is nothing behind the collection of attributes. The attributes are the real things, the material world is but the objectification of the Absolute Being; it is the other self of the Absolute - another which owes its existence to the principle of difference in the nature of the Absolute itself. Nature is the idea of God, a something necessary for His knowledge of Himself. While Hegel calls his doctrine the identity of thought and being, Al-Jīlī calls it the identity of attribute and reality. It should be noted that the author's phrase, “world of attributes”, which he uses for the material world is slightly misleading. What he really holds is that the distinction of attribute and reality is merely phenomenal, and does not at all exist in the nature of things. It is useful, because it facilitates our understanding of the world around us, but it is not at all real. It will be understood that Al-Jīlī recognises the truth of Empirical Idealism only tentatively, and does not admit the absoluteness of the distinction. These remarks should not lead us to understand that Al-Jill does not believe in the objective reality of the thing in itself. He does believe in it, but then he advocates its unity, and says that the material world is the thing in itself; it is the “other”, the external expression of the thing in itself. The Ding an sick and its external expression or the production of its self-diremption, are really indentical, though we discriminate between them in order to facilitate our understanding of the universe. If they are not identical, he says, how could one manifest the other? In one word, he means by Ding an sick, the Pure, the Absolute Being, and seeks it through its manifestation or external expression. He says that as long as we do not realise the identity of attribute and reality, the material world or the world of attributes seems to be a veil; but when the doctrine is brought home to us the veil is removed; we see the Essence itself everywhere, and find that all the attributes are but ourselves. Nature then appears in her true light; all otherness is removed and we are one with her. The aching prick of curiosity ceases, and the inquisitive attitude of our minds is replaced by a state of philosophic calm. To the person who has realised this identity, discoveries of science bring no new information, and religion with her role of supernatural authority has nothing to say. This is the spiritual emancipation.

Let us now see how he classifies the different divine names and attributes which have received expression in nature or crystallised Divinity. His classification is as follows:

(1). The names and attributes of God as He is in Himself (Allāh, The One, The Odd, The Light, The Truth, The Pure, The Living.)

(2). The names and attributes of God as the source of all glory (The Great and High, The All-powerful).

(3). The names and attributes of God as all Perfection (The Creator, The Benefactor, The First, The Last).

(4). The names and attributes of God as all Beauty (The Uncreatable, The Painter, The Merciful, The Origin of all). Each of these names and attributes has its own particular effect by which it illuminates the soul of the perfect man and Nature. How these illuminations take place, and how they reach the soul is not explained by Al-Jīlī. His silence about these matters throws into more relief the mystical portion of his views and implies the necessity of spiritual Directorship.

Before considering Al-Jīlī's views of particular Divine Names and Attributes, we should note that his conception of God, implied in the above classification, is very similar to that of Schleiermacher. While the German theologian reduces all the divine attributes to one single attribute of Power, our author sees the danger of advancing a God free from all attributes, yet recognises with Schleiermacher that in Himself God is an unchangeable unity, and that His attributes “are nothing more than views of Him, from different human standpoints, the various appearances which the one changeless cause presents to our finite intelligence according as we look at it from different sides of the spiritual landscape.”

In His absolute existence He is beyond the limitation of names and attributes, but when He externalises Himself, when He leaves His absoluteness, when nature is born, names and attributes appear sealed on her very fabric.

We now proceed to consider what he teaches about particular Divine Names and Attributes. The first Essential Name is Allāh (Divinity) which means the sum of all the realities of existence with their respective order in that sum. This name is applied to God as the only necessary existence. Divinity being the highest manifestation of Pure Being, the difference between them is that the latter is visible to the eye, but its where is invisible; while the traces of the former are visible, itself is invisible. By the very fact of her being crystallised divinity, Nature is not the real divinity; hence Divinity is invisible, and its traces in the form of Nature are visible to the eye. Divinity, as the author illustrates, is water; nature is crystallised water or ice; but ice is not water. The Essence is visible to the eye, (another proof of our author's Natural Realism or Absolute Idealism) although all its attributes are not known to us. Even its attributes are not known as they are in themselves, their shadows or effects only are known. For instance, charity itself is unknown, only its effect or the fact of giving to the poor, is known and seen. This is due to the attributes being incorporated in the very nature of the Essence. If the expression of the attributes in its real nature had been possible, its separation from the Essence would have been possible also. But there are some other Essential Names of God - The Absolute Oneness and Simple Oneness. The Absolute Oneness marks the the first step of Pure Thought from the darkness of Cecity (the internal or the original Māyā of the Vedānta) to the light of manifestation. Although this movement is not attended with any external manifestations, yet it sums up all of them under its hollow universality. Look at a wall, says the author, you see the whole wall; but you cannot see the individual pieces of the material that contribute to its formation. The wall is a unity - but a unity which comprehends diversity, so Pure Being is a unity but a unity which is the soul of diversity.

The third movement of the Absolute Being is Simple Oneness - a step attended with external manifestation. The Absolute Oneness is free from all particular names and attributes. The Oneness Simple takes on names and attributes, but there is no distinction between these attributes, one is the essence of the other. Divinity is similar to Simple Oneness, but its names and attributes are distinguished from one another and even contradictory, as generous is contradictory to revengeful.

The third step, or as Hegel would say, Voyage of the Being, has another appellation (Mercy). The First Mercy, the author says, is the evolution of the Universe from Himself and the manifestation of His own Self in every atom of the result of His own self-diremption. Al-Jīlī makes this point clearer by an instance. He says that nature is frozen water and God is water. The real name of nature is God (Allah); ice or condensed water is merely a borrowed appellation. Elsewhere he calls water the origin of knowledge, intellect, understanding, thought and idea. This instance leads him to guard against the error of looking upon God as immanent in nature, or running through the sphere of material existence. He says that immanence implies disparity of being; God is not immanent because He is Himself the existence. Eternal existence is the other self of God, it is the light through which He sees Himself. As the originator of an idea is existent in that idea, so God is present in nature. The difference between God and man, as one may say, is that His ideas materialise themselves, ours do not. It will be remembered here that Hegel would use the same line of argument in freeing himself from the accusation of Pantheism.

The attribute of Mercy is closely connected with the attribute of Providence. He defines it as the sum of all that existence stands in need of. Plants are supplied with water through the force of this name. The natural philosopher would express the same thing differently; he would speak of the same phenomena as resulting from the activity of a certain force of nature; Al-Jīlī would call it a manifestation of Providence; but, unlike the natural philosopher, he would not advocate the unknowability of that force. He would say that there is nothing behind it, it is the Absolute Being itself.

We have now finished all the essential names and attributes of God, and proceed to examine the nature of what existed before all things. The Arabian Prophet, says Al-Jīlī, was once questioned about the place of God before creation. He said that God, before the creation, existed in “Amā” (Blindness). It is the nature of this Blindness or primal darkness which we now proceed to examine. The investigation is particularly interesting, because the word translated into modern phraseology would be “The Unconsciousness”. This single word impresses upon us the foresightedness with which he anticipates metaphysical doctrines of modern Germany. He says that the Unconsciousness is the reality of all realities; it is the Pure Being without any descending movement; it is free from the attributes of God and creation; it does not stand in need of any name or quality, because it is beyond the sphere of relation. It is distinguished from the Absolute Oneness because the latter name is applied to the Pure Being in its process of coming down towards manifestation. It should, however, be remembered that when we speak of the priority of God and posteriority of creation, our words must not be understood as implying time; for there can be no duration of time or separateness between God and His creation. Time, continuity in space and time, are themselves creations, and how can piece of creation intervene between God and His creation. Hence our words before, after, where, whence, etc., in this sphere of thought, should not be construed to imply time or space. The real thing is beyond the grasp of human conceptions; no category of material existence can be applicable to it; because, as Kant would say, the laws of phenomena cannot be spoken of as obtaining in the sphere of noumena.

We have already noticed that man in his progress towards perfection has three stages: the first is the meditation of the name which the author calls the illumination of names. He remarks that “ When God illuminates a certain man by the light of His names, the man is destroyed under the dazzling splendour of that name; and “when thou calleth God, the call is responded to by the man”. The effect of this illumination would be, in Schopenhauer's language, the destruction of the individual will, yet it must not be confounded with physical death; because the individual goes on living and moving like the spinning wheel, as Kapila would say, after he has become one with Prakriti. It is here that the individual cries out in pantheistic mood:She was I and I was she and there was none to separate us.”

The second stage of the spiritual training is what he calls the illumination of the Attribute. This illumination makes the perfect man receive the attributes of God in their real nature in proportion to the power of receptivity possessed by him - a fact which classifies men according to the magnitude of this light resulting from the illumination. Some men receive illumination from the divine attribute of Life, and thus participate in the soul of the Universe. The effect of this light is soaring in the air, walking on water, changing the magnitude of things (as Christ so often did). In this wise the perfect man receives illumination from all the Divine attributes, crosses the sphere of the name and the attribute, and steps into the domain of the Essence - Absolute Existence.

As we have already seen, the Absolute Being, when it leaves its absoluteness, has three voyages to undergo, each voyage being a process of particularisation of the bare universality of the Absolute Essence. Each of these three movements appears under a new Essential Name which has its own peculiar illuminating effect upon the human soul. Here is the end of our author's spiritual ethics; man has become perfect, he has amalgamated himself with the Absolute Being, or has learnt what Hegel calls The Absolute Philosophy. “He becomes the paragon of perfection, the object of worship, the preserver of the Universe”42 He is the point where Man-ness and God-ness become one, and result in the birth of the god-man.

How the perfect man reaches this height of spiritual development, the author does not tell us; but he says that at every stage he has a peculiar experience in which there is not even a trace of doubt or agitation. The instrument of this experience is what he calls the Qalb (heart), a word very difficult of definition. He gives a very mystical diagram of the Qalb, and explains it by saying that it is the eye which sees the names, the attributes and the Absolute Being successively. It owes its existence to a mysterious combination of soul and mind; and becomes by its very nature the organ for the recognition of the ultimate realities of existence. All that the “heart”, or the source of what the Vedānta calls the Higher Knowledge, reveals is not seen by the individual as something separate from and heterogeneous to himself; what is shown to him through this agency is his own reality, his own deep being. This characteristic of the agency differentiates it from the intellect, the object of which is always different and separate from the individual exercising that faculty. But the spiritual experience, according to the Sufīs of this school, is not permanent; moments of spiritual vision, says Matthew Arnold,

cannot be at our command. The god-man is he who has known the mystery of his own being, who has realised himself as god-man; but when that particular spiritual realisation is over man is man and God is God. Had the experience been permanent, a great moral force would have been lost and society overturned.