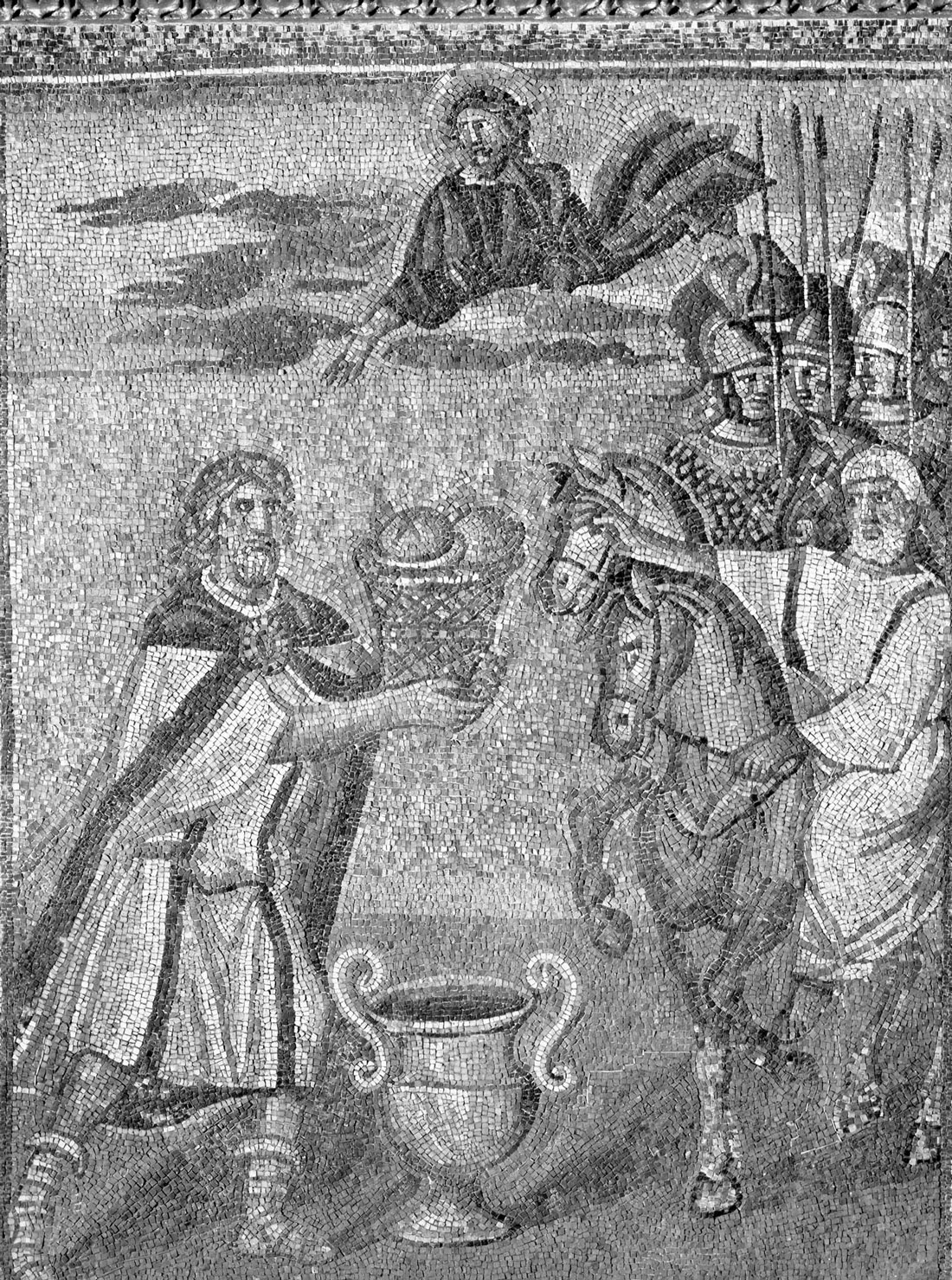

Figure 3. The Ark of the Covenant being carried across the Jordan. Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome. Photo courtesy of Art Resource.

Clothild commissioned a Marian church to be built on the Seine where many miracles occurred;

Radegund finally gained her freedom from King Clothar at an oratory dedicated to Mary;

and Rusticula was buried in Saint Mary’s Basilica, to the altar’s right hand.

In all these instances, holy women sought association with Marian edifices where miracles immediately followed. Because of that alliance both the Marian cult and the holy women themselves gained spiritual prestige.

Spiritual authority did not simply end at death, however. According to her hagiographers, immediately after her death Rusticula’s soul ascended to Christ’s right hand, although her corpse remained at the right side of Mary’s altar in a Marian basilica. Rusticula had finally joined the heavenly “chorus of virgins in which the Blessed Virgin Mary holds first place.”

Yet Rusticula was not absent from her community; even from heaven she guarded her flock as a pious mother. In many of her postmortem miracles, she cured the sick “handmaids of Christ” at her convent. Her hagiographer noted that even after death this holy mother (Rusticula, not the Virgin Mary) “exercised the same care and solicitude as when she was living in the body.”

Glodesind, abbess at Metz, also governed her convent from beyond the grave. Her biographer recognized that the abbess, after her body’s interment at a Marian church, “still rules though she rests in her grave.”

Monastic families were thus seldom separated; earthly virgins identified with the chorus of heavenly virgins singing at the throne of God while their spiritual mothers sat by Mary’s right hand. Marian altars and basilicas were visual reminders of her sublime position, as well as her authority, an authority that could sometimes be lent to prominent abbesses who governed in her name.

Many abbesses were not satisfied with sitting at Mary’s right hand in heaven; they also wanted their bodies to rest near the high altars of their churches. This sometimes required miraculous intervention because the male clergy, as altar servants, ultimately controlled the altar and its surrounding sacred space. The clergy’s authority only multiplied as the attention to relics and dead body parts proliferated throughout Merovingian Gaul.

As saint veneration became more popular in the early Middle Ages, church architecture had to change. Late antique church styles had limited the number of people who could directly encounter the holy relics; but by the fifth century more people wanted greater access to the holy. Church councils soon encouraged all altars to include relics of a saintly bishop or martyr; the Fifth Council of Carthage in 401 even declared that altars without dead body parts should be destroyed.

Pious congregations also required that saints’ relics be visible and accessible: Christians desired admittance to the relics in order to kiss, touch, or bow to them. The Church of Mary’s Tomb in Gethsemane provided a series of slots so that pilgrims could insert their hands and feel the sarcophagus.

Close proximity to the holy was indeed a prized treasure, and early Medieval architectural innovations had to allow some direct access (however limited).

Merovingian architects had to contend first with the issue of space. The earliest church altars had restricted any direct contact between petitioners and holy relics because they were constructed over the lower levels of catacombs. Priests conducted mass over the small crypts, but only small groups of people entered the modest space. As the saints’ popularity grew, architects incorporated shafts that reached from the altar on the main level to the tombs below.

Pious petitioners could communicate with the saints down the shafts or lower items to touch the holy crypts (thus creating contact relics).

With the Merovingians, church builders moved the tombs to the main levels and displayed the holy relics in the church’s holy space. Hagiographers often characterized the saint’s presence as a celestial light permeating the room; and, they claimed, this radiance touched not only the heart but also the soul. Gregory of Tours described Mary’s relics as a “radiating light” from the altar at Clermont.

Everyone in the vast space then had virtual proximity to the holy.

The clergy, however, did not surrender control of the relic itself. Either in a barricaded oratory or through an enclosed shaft, the church tightened its regulation of the saint cults (thereby further mystifying the holy). This trend only accelerated. Whereas Merovingian hagiography encouraged its audience to kiss and touch holy items, Carolingian authors betrayed the impossibility of such proximity. By the late eighth century, Carolingian hagiographers enjoined their audience to gaze upon the holy wonders and glittering spectacles of the distant sarcophagi.

In this hierarchical schema, with the most holy on display to the most pious, prominent bishops, abbots, and holy figures competed for eternal rest beside the high altar. Beginning in the sixth century, holy men and women might be interred within the church walls, but after miraculous signs their bodies could advance toward the high altar. This prestigious spot was of course the place of great honor, and several saints expressed their desire to be promoted through miraculous visions. After proper exhumation, the saintly bodies (usually churchmen and abbesses from royal stock) could be moved down the aisle symbolically closer to Christ.

Saint Germanus of Paris (d. 576), for example, appeared to a pious woman two hundred years after his first burial and requested better accommodations behind the main altar.

Glodesind of Metz also ordered (posthumously) that a church be erected to the Blessed Virgin Mary near her convent. After the church’s construction, the abbess’s body was disinterred and moved to its second resting place within the Marian church’s walls (ca. seventh century). Later, in 830, the bishop of Metz noticed that Glodesind’s tomb emerged from the earth. He reckoned this portent signaled Glodesind’s desire to move yet again. After much prayer the priests moved the holy corpse to a third and final resting place “in the monastery’s older church behind the altar which had been built and consecrated in praise of the Holy Mother of God, Mary, and Saint Peter, the Prince of the Apostles.”

After this final translation, Glodesind worked many miracles that attracted many pilgrims and enjoyed an even more revered status among her family’s dead.

By the seventh century holy bodies such as Glodesind’s could be moved at will to illustrate their celestial status but only after the approval of the male episcopacy.

Fatima and the ahl al-bayt in Built Form

Muslim artists neither decked walls with Fatima mosaics nor constructed statues in her likeness; yet Shi`ite material culture certainly realized her sublime station as mother and intercessor. One of the most poignant displays of Fatima’s sublime authority is present in the mosque itself. Some Shi`ite exegetes correlate Fatima with the mosque’s prayer niche, or mihrab. This architectural design might signify for a Shi`ite audience a visual metaphor for Fatima’s intercessory powers.

The mihrab is one among many architectural designs that delineate and adorn the mosque as sacred space. The boundaries of that sacred space often shifted, however; the medieval mosque functioned equally as a civic structure. Caliphs and local political authorities made public speeches from its stages; in the daytime it sometimes hosted trade shows; and at night it provided a shelter for the local homeless.

The mosque did maintain one distinct spiritual function: it offered a place of prayer (masjid, a place of prostration).

As a sacred place of prayer, the mosque exhibited Qur’anic verses and prayers inscribed in Arabic calligraphy, a medieval art form in its own right.

This calligraphy was intended not only as decoration but also as a focus of meditation. The mosque also contained architectural styles that distinguished its spiritual function. The imam, or prayer leader (distinct from the Shi`ite Imams, descendants of `Ali and Fatima), usually stood at a pulpit (minbar) to deliver his Friday sermon; ablution pools conferred ritual purity; and the Qur’an rested upon a chair (kursi) in high honor. All these elements might have contained elaborate calligraphic or even geometric ornamentation, or they might have remained quite plain. One of the true focal areas of the mosque was the mihrab, which functioned as a pointer of sorts; it oriented the worshiper toward Mecca for obligatory prayers.

The mihrab has a complicated history. Its basic design, ascertained from both textual description and archaeological evidence, contains an arch, supporting columns, and the empty space between them.

Most scholars agree that in pre-Islamic Arabia the mihrab designated a place of royal ascendancy or a place of honor in palaces.

In religious contexts the mihrab referred to a sanctuary or holy place that probably housed cultic images. In ancient Semitic cultures it was probably portable; Bedouin tribes used it to transport their gods and, for early Jewish tribes, to orient themselves toward Jerusalem.

The mihrab in its religious function symbolized a doorway from the mundane to the sacred, from this world to the next.

Shi`ite hagiographers assimilate Fatima to this doorway, this empty space. In one hadith mentioned above, Fatima stands illuminating the Muslim community with her sublime light at times of obligatory prayer. Her father, Muhammad, commands his community to orient themselves toward her. She becomes the mihrab, pointing her people toward Mecca.

Traditional mosque design places a hanging lamp within that mihrab and engraves either on the lamp itself or somewhere nearby the very pertinent Qur’anic Light Verse (24.35):

Allah is the Light of the heavens and earth. The parable of His Light is as if there were a niche and within it a lamp: the lamp enclosed in glass: the glass as it were a brilliant star.

The mihrab’s design, as a visual metaphor, correlates the hanging lamp with Fatima, who contains within herself the light of the Imams (often associated with the star). Just as Mary provided an empty space for God to dwell, Fatima’s body enclosed the nur of the Imams. Residing in the symbolic portal between heaven and earth, Fatima offers the hope of intercession and prayer on behalf of her adopted kin.

All Muslims, Sunni and Shi`i, associate the mihrab as a prayer portal pointing toward Mecca; but for Shi`ite viewers, the mihrab lamp might also signify Fatima’s intercessory station. Often Shi`ite artists chose to present the entire holy family rather than the holy mother alone. Throughout Iran and Iraq, for example, five hanging lamps often adorn a central mihrab symbolizing the five members of the ahl al-bayt.

Calligraphic inscriptions of the Twelve Imams’ names and their miracles might also outline the mihrab, further identifying its Shi`ite audience.

The association between Fatima and the mihrab, however symbolic, also resonates with Islamic traditions about Mary and her own mihrab.

According to the Qur’an, Zechariah (John the Baptist’s father) cared for Mary after her parents dedicated her to the Temple. Each time Zechariah would visit his charge in her mihrab, he found her miraculously supplied with food (Qur’an 3.36-37). Muslim exegetes as early as the eighth century linked Mary’s mihrab with the Bayt al-Maqdis, a mosque in Jerusalem.

Mary was believed to have lived in the mosque’s inner sanctum and there received food from Allah. By the eleventh century, pilgrimage guides combined Mary’s mihrab with `Isa’s (Jesus’) cradle, both located on the Temple platform.

Ottoman Turks later engraved the verse describing Mary’s mihrab above their own mosques’ mihrabs. Mary, along with Fatima in Shi`ite tradition, remained closely linked with this prayer portal.

Until recently most art historians have failed to appreciate fully the distinctions between Sunni and Shi`ite material culture. They have instead marginalized Shi`ism as a heterodoxy and categorized its styles as exceptional. Yet there is evidence that many forms of Islamic architecture held different meanings for Shi`ite communities and their Sunni counterparts. Mausoleums constructed for the Imams and their families, for example, played an important part in defining holy space. When Sunni Muslims conquered Shi`ite areas, they usually first sacked the shrines as a symbol of Shi`ite defeat, both physical and theological. While Shi`ite architects constructed and transformed mausoleums in a variety of patterns, they also built some with twelve sides representing the Twelve Imams. Distinctively Shi`ite interpretation of Islamic art and architecture has yet to be fully explored.

One current study has attempted to fill that scholarly lacuna by examining the mosque /mausoleum Gunbad-i `Alawiyan at Hamadan, Iran.

Through comparative analysis, the work isolated some basic Shi`ite architectural and commemorative patterns. First, at the Hamadan mosque twelve arches line the interior lower division; this might refer to the Twelve Imams. Each of the corner towers contain a series of five arched units that might signify the ahl al-bayt.

Second, the interior and exterior walls incorporate popular Qur’anic verses among Shi`ite mosques.

Qur’an 5.55, for example, explains:

Your [real] friends are [no less than] Allah, His Messenger, and the Believers - those who establish regular prayers and pay zakat [or tithes] and they bow down humbly [in worship].

At first this verse appears rather nonsectarian: it repeats the basic formulation of the faith (shahada) by reaffirming Allah and his messenger, Muhammad; and it introduces some of the basic tenets of ritual praxis (prayer, tithing, etc.). According to the twelfth-century Shi`ite exegete al-Fadl ibn al-Hasan al- Tabarsi, this passage discloses an esoteric message commending `Ali and the ahl al-bayt.

The “believers,” says al- Tabarsi, should be read in the singular, and that singular believer refers to `Ali: “Your (real) friends are (no less than) Allah and His messenger and `Ali.” According to this interpretation, Allah ordained `Ali (and his implied family) as his intercessor just as the prophet Muhammad. The Shi`ite exegete and the calligraphic inscription reminds the viewer of the family’s exalted status.

Finally, the Hamadan mosque/mausoleum incorporates a mihrab adorned in a Shi`ite pattern. Like most other prayer niches, even those of Sunni persuasion, this mihrab includes the Throne Verse (Qur’an 2.255):

He knows what (appears to His creatures as) before or after or behind them. Nor shall they compass aught of His knowledge except as He wills. His Throne does extend over the heavens and the earth, and He feels no fatigue in guarding and preserving them.

For a non-Shi`ite Muslim, this verse confirms Allah’s expansive power; his throne symbolizes the beginning and end of all creation and the cosmos.

Shi`ite viewers (especially those in the medieval period), however, might associate the throne with the Imams as well: they existed, engraved on the throne of God, since before created time.

The verse thus links the Imams’ authority directly with Allah’s celestial realm.

Other art historians have suggested that Islamic art and architecture might reveal a sectarian split in subtler ways, particularly during the eleventh- and twelfth-century Sunni revival. During these centuries, Sunni (particularly Seljuk Turk) authorities encouraged a more uniform Islam not only through legal and theological argument but also through material culture. Calligraphic inscriptions at mosques and madrasas (theological colleges) emphasized Sunni, particularly Ash`ari, ideals with increasingly standardized forms.

Calligraphic script, for example, shifted from the largely illegible Kufic style to a legible cursive. This script subtly challenged the Shi`ite recognition of both esoteric (batin, or hidden) and exoteric (zahir, or external) truth; with the new script, only one reading and one interpretation prevailed.

The Safavid regime, in contrast, devoted considerable means to building pilgrimage sites and shrines to the Imams and their families, demonstrating their Shi`ite identity. Safavid royal women in particular endowed the shrine of Fatima al-Ma`suma, the eighth Imam `Ali b. Musa al-Reza’s sister, in Qum. Shi`ite Safavids widely recognized Fatima al-Ma`suma as the principal intercessor for women. According to tradition, she arrived in Qum in 817 on her way to visit her brother-Imam, but she became ill and requested burial there in the cemetery gardens. The shrine built at her tomb became a popular pilgrimage site by the ninth and tenth centuries.

Several Safavid women identified themselves with Fatima al-Ma`suma and her namesake, Fatima (Muhammad’s daughter). Histories and hagiographies alike celebrated their reputations as pious mothers, daughters, and brides.

With the contributions of Safavid queens and royalty, Fatima al-Ma`suma’s dome was rebuilt and calligraphic inscriptions adorned the courtyard and inner tomb chamber. These inscriptions included hadith that threatened with hellfire anyone who opposed the ahl al-bayt and likened the holy family to Noah’s ark. The inscriptions also awarded the Safavid donors epithets similar to their heavenly prototype, Fatima al-Batul (the Virgin) and Fatima al-Zahra (the Radiant).

The holy family’s fame extends beyond the mosque, madrasa, and shrines into many homes as artists inscribe the names of the ahl al-bayt and the Twelve Imams as a type of magical formula on wall hangings or even domestic items.

Scholars typically sanction such practices as long as the articles refer to Allah and Muhammad’s family, although religious authorities strictly forbid any illustration that appeals to alternate powers such as the jinn, demons, or false gods. Among Shi`ite communities, amulets and sacred artifacts usually entreat the holy family to intervene against the evil eye. The most common symbol of this sacred mediation is the human hand.

Because it recalls Allah and the Imams as authorities, it remains licit for most Shi`ite communities (fi g. 4).

The hand amulet as it is used in various cultures also seems to challenge traditional gender expectations. Most good luck talismans throughout the Middle East and Africa appeal to masculine, phallic imagery.

The hand amulet, however, alludes to a mother and her family, and it is equally popular among both genders, in both public and private space. While women often wear the symbol as jewelry, men invoke its powers as symbolic stamp or insignia: it is used in official business transactions, on modes of transportation (camels or automobiles), and on entrances to homes and offices. The holy family’s authority, with Fatima at its nexus, supersedes traditional gender designations and promises active intercession available through a mother, bride, and daughter.

Despite the disparate theologies surrounding images and pictorial displays, both Christian and Shi`ite artists managed to reveal Mary’s and Fatima’s sublime authority in built form. Artists and architects situated both women’s imagery in sacred space: Mary was both prefigured and depicted in Santa Maria Maggiore’s mosaic cycle, and later priests associated her with the high altar. Fatima’s authority might be symbolized in mosque lamps as well as the mihrab itself. In both traditions, these

10%

10%

Author: Mary F. Thurlkill

Author: Mary F. Thurlkill