Conclusion

According to early medieval Christian and Shi`ite tradition, God chose Mary and Fatima as vessels for his sublime progeny. Mary, an obedient maiden, gave birth to the God-Man Jesus; Fatima, sharing in the divine nur, held the Imamate within her womb. The attention to two female figures did not stop with theological concerns; hagiographers also chose Mary and Fatima to think about matters of political and sectarian identity. The sacred narratives and hagiographies produced by these authors, most of whom were men, offer historians windows into theology, gender expectations, and notions of the holy. If we read these texts with a critical eye to rhetorical design and cultural context, they reveal a complex construction of feminine images intended for a variety of purposes and audiences.

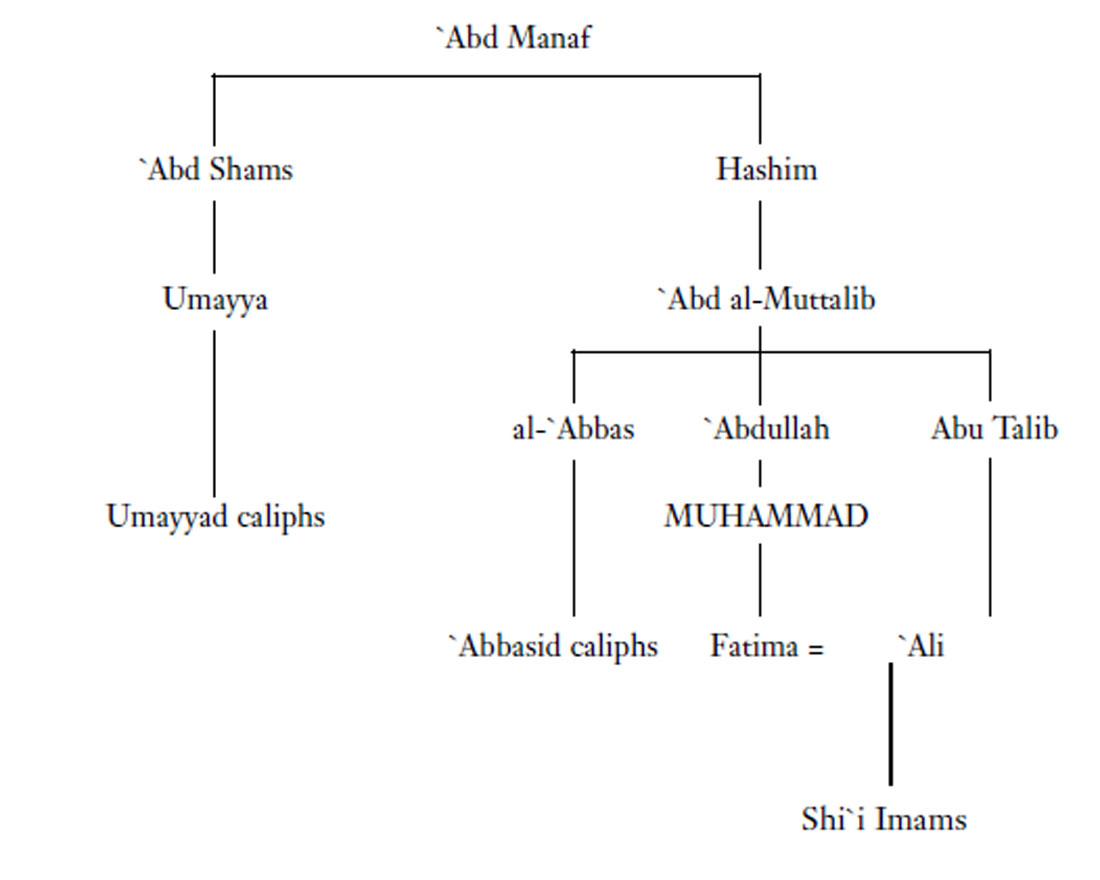

A careful comparison of Mary and Fatima depends on problematic sources. Late antique and early medieval authors proliferated images of Mary and Fatima at times of social, political, and religious change. Christian authors from roughly 200 to 750, for example, employed Mary as a symbol of the orthodox or right church as well as to bolster their Christology. Shi`ite authors used the image of Fatima in a similar way; however, their texts originate from a different time and space. Shi`ite hadith transmitters stressed Fatima’s role in the Imamate, the Prophet Muhammad’s lineage that held true religious authority among Muslims. Such texts, dating to the eighth and ninth centuries, allowed various Shi`ite groups to express their differences (e.g., on the Imams’ identities) as well as the emerging distinction between Sunni and Shi`ite. Both Christian and Shi`ite texts thus reveal a process of self-identification wherein male authors rely on feminine ideals as markers of community.

Theologians clearly relied on Mary and Fatima to articulate and expand their respective orthodoxies and notions of rightness. By defining first their pure and immaculate nature, authors transformed Mary’s and Fatima’s bodies into sacred containers. Early church fathers such as Ambrose and Jerome explained Jesus’ own miraculous composition as both human and divine by scrutinizing Mary’s body, miraculously pure and intact. In developing their Mariology, theologians developed their Christology. Ambrose transformed Mary into a new Hebrew temple, sealed to all except the High Priest, or God himself. Fatima also served as a sacred vessel, holding the Imam’s nur within her while simultaneously sharing it. Fatima al-Zahra existed as the only female member of the holy family and, like her father, husband, and sons, remained immaculate and infallible. Both Shi`ite and Christian authors also likened their holy women to an ancient container, Noah’s ark; the women’s wombs carried humanity’s true salvation.

Mary and Fatima served equally important functions in political and sectarian discourse. With such a rhetorical agenda in mind, hagiographers accented Mary’s and Fatima’s maternal roles. These holy women, as mothers, effectively defined the limits of community and sectarian division. By symbolically adopting believers to their maternal care, Mary and Fatima damned unbelievers to hell. Hagiographers advertised their holy mothers by describing their homey miracles and domestic skill. Both women experienced super human parturitions, multiplied food, and interceded for their spiritual offspring.

In the early medieval West, Mother Mary identified Franks as orthodox and anointed by God. When the Merovingians converted to Christianity, Mary defended her children against Arian and Jewish contamination. Merovingian priests, bishops, queens, and holy women sometimes defined themselves through Mary: bishops boasted of her relics; queens dedicated their families and Gallo-Roman populations to her care; and holy women nurtured their communities as pious mothers.

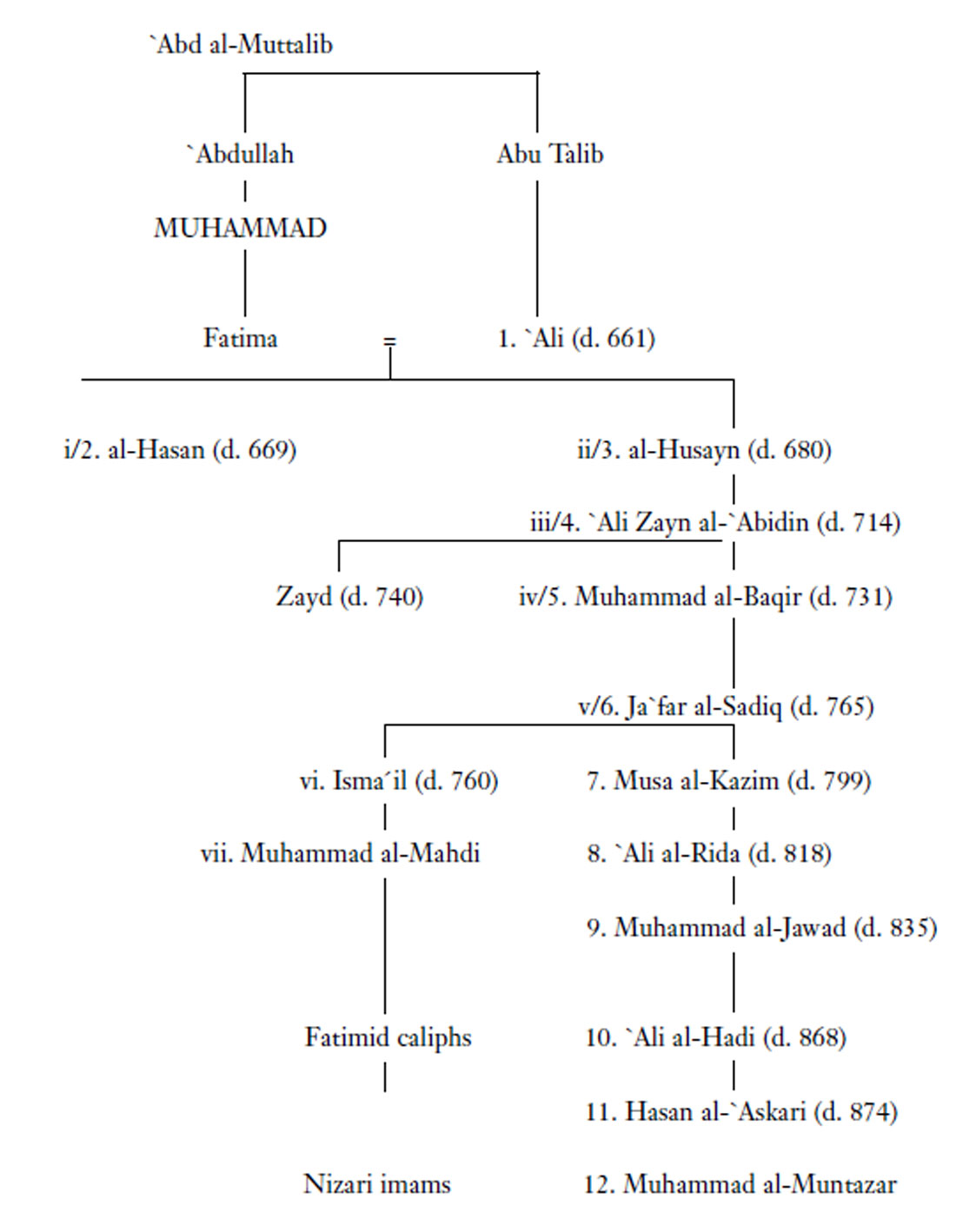

Shi`ite authors articulated the Imamate’s divine authority as the community’s leaders by advertising Fatima’s motherhood in much the same way. Fatima gave birth free from pollutants and simultaneously shared in the preexistent nur from which Allah crafted the ahl al-bayt. Shi`ite authors declared their sectarian identity by proclaiming Fatima’s numinous status as the Prophet’s daughter, `Ali’s wife, and the Imams’ mother. She provided the uterine connection, the bloodline, that authorized the Imams’ station as the Shi`ite community’s infallible leaders. The identification with Fatima’s family granted considerable prestige in the struggle between Sunni and Shi`ite sovereignty as well as clerical responsibility in Shi`ite communities. The Shi`a demonstrated its blessed status by describing Fatima’s abasement of `A’isha and distinction as the Prophet’s daughter. For the majority of Shi`ites (or Twelvers), the Imamate’s authority shifted with the twelfth Imam’s occultation in the tenth century. When the last Imam remains in hiding, the Shi`ite community’s clerics or scholars rule in his stead. By fortifying the link between Fatima and the Imams, these scholars secured their own authority within Shi`ism.

Mary’s and Fatima’s chosen status reveals much about gender designations in medieval Christianity and Islam. Both traditions labeled women as spiritually depraved descendants of Eve especially susceptible to temptation and sin. To transform Mary and Fatima into worthy vessels, God first redeemed them from the physical burdens borne by the rest of their sex. Mary remained physically intact and Fatima remained ritually pure while performing miraculous deeds. These divergent religions provide radically different idealized female bodies: Mary as virgin remains impenetrable; the heavenly Fatima and houris retain their virginity while engaging men with unusual sexual stamina.

It is clear that ordinary women could never achieve the same emancipation as their holy models and thus appear as the ideal female form, yet they still operated in the same patriarchal systems that both feared and sought to contain female sexuality and pollution. By appropriating the image of Mary and Fatima to their own circumstance, it seems many women succeeded in gaining some amount of spiritual authority. As mothers and brides, Merovingian queens and abbesses converted their families, wielded royal might, and (effectively) ruled monasteries. While not the focus of this study, it seems that Shi`ite royal women such as those in the Safavid dynasty, self-styled in Fatima’s image, endowed shrines from their own estates.

Both Mary and Fatima, in a sense, draw their spiritual authority from the family and domestic sphere. Early church fathers explained that Mary never left home and remained under the protection of male priests and her husband, Joseph, while at the same time she intercedes for humanity and reigns in heaven as Christ’s mother and bride. Fatima, the mystical nexus of the holy family, rewards her adoptive kin who weep for her slain son, Husayn, and escorts women into paradise on judgment day. Because these women are both powerful in their own right yet intimately connected to domestic (private) space, they can be employed by authors for a variety of purposes. Mary and Fatima can signify both female independence and agency and submission and chastity. The tendency to imbue Mary and Fatima with such symbolic meaning for a specific political purpose is not unique to the medieval period.

Contemporary Catholic Christians have attributed a plethora of meanings and interpretations to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

When Mary appeared to three children in Fatima, Portugal, in 1917, the church explained that she promised Communism’s demise if believers would live pious lives and pray to her. The Polish Pope John Paul II later credited Mary with Communism’s defeat in the late 1980s and encouraged the church to continue its Marian piety.

Mary, champion of democracy, vanquished Russia’s secular regime. Yet Mary provides more than political identity; many inner-city gangs in the United States use Mary as a symbol of their (usually ethic) communities. Gang members, usually Latino, often have Mary of Guadalupe, a sixteenth-century visionary icon, tattooed on their backs to demonstrate their gang allegiance.

The more conservative elements within Catholicism certainly have a vested interest in limiting Mary to traditional ideals. These forces advance Mary as the feminine model in the twenty-first century to counteract what they deem rampant sexual promiscuity. Mary, as Virgin, provides young women with a path of life - virginity through abstinence, which leads to marriage and procreation. More important, Mary provides a model of sub mission, denying her (and women) a priestly role. More liberal, feminist elements within the church demand that Mary be reimagined. For these groups, historical interrogation and biblical scholarship leads to a more complex view of Mary; in this reconstruction, Mary resembles an independent woman, free to choose her future.

Many feminist Catholics want to emphasize the medieval Marian epithets Co-Redeemer and Mediatrix to revitalize women’s roles in the church.

Similarly, modern Muslim authors appeal to Fatima in support of their political and religious causes. Shi`ite adoration of Fatima continues today, most prominently in taziya ceremonies that re-create Husayn’s death and suffering. These passion narratives appear in the Buyid period (tenth century) in recitation form and became actual dramatizations by the Safavid era. One nineteenth-century observation of an Iranian taziya describes Fatima in much the same language as her medieval hagiographers: the author defines her as one of the “best of the women of the world”; she is called al-batul, the virgin, and al-zahra, the radiant; and he commends her perpetual virginity as the “Mary of this people.”

More recent ethnographies describe Fatima’s miraculous appearance during celebrations related to the Karbala massacre. Fatima joins the faithful group of women while they recount her many miracles and acts of humility, strength, and piety.

According to some practitioners, Fatima miraculously attends the various ceremonies that re-create Husayn’s martyrdom and notes who participates in her son’s suffering. She observes the matam rituals wherein believers beat their breasts or inflict bleeding wounds on their bodies to share in Husayn’s pain. By her presence, Fatima creates a sacred space and time in which the believers’ suffering joins with the ahl al-bayt’s at Karbala. She then returns to paradise, pleased with her community’s loyalty.

Iranian leaders put Fatima to more rhetorical use during the Iranian Revolution in the 1970s. Idealogues such as `Ali Shariati presented Fatima as a critique of Western women who are merely pawns of capitalism and materialism. Shariati encouraged young Iranian women to first imitate Fatima as a protector of Islamic law and justice but then to return to home and family after the revolutionary struggle.

Most revolutionaries described Zaynab, Fatima’s daughter, as the paradigm for political action. Zaynab was present at Husayn’s martyrdom at Karbala and denounced the caliph’s humiliation of her brother’s body. Women should imitate Zaynab in their political resurgence, but, according to Shariati, they should follow Fatima as an example of political responsibility followed by domestic quietude. Zaynab might be used for revolutions and reform, but Fatima provides the idealized woman for more typical times.

Whether in the seventh century or the twenty-first, Mary’s and Fatima’s charisma affords scholars and religious alike an important symbol of community and religiosity that may be manipulated in various ways. The holy women’s attendance within the home subtly stresses the male householders’ presence and dominance. In the end, however, Mary and Fatima - chosen by God as holy vessels and chosen by men as didactic models - manage to provide moral exemplars for women, promote standards of sanctity and faith, and chastise religious and political heresy. Within such legacies the domestic indeed complements public (masculine) authority and gains a place for feminine sanctity not easily ignored.

0%

0%

Author: Mary F. Thurlkill

Author: Mary F. Thurlkill