Al-Mizan: An Exegesis of the Qur'an Volume 7

0%

0%

Author: Allamah Sayyid Muhammad Husayn Tabatabai

Author: Allamah Sayyid Muhammad Husayn Tabatabai

Translator: Allamah Sayyid Sa'eed Akhtar Rizvi

Publisher: World Organization for Islamic Services (WOFIS)

Category: Quran Interpretation

Author: Allamah Sayyid Muhammad Husayn Tabatabai

Translator: Allamah Sayyid Sa'eed Akhtar Rizvi

Publisher: World Organization for Islamic Services (WOFIS)

Category:

Download: 7136

Comments:

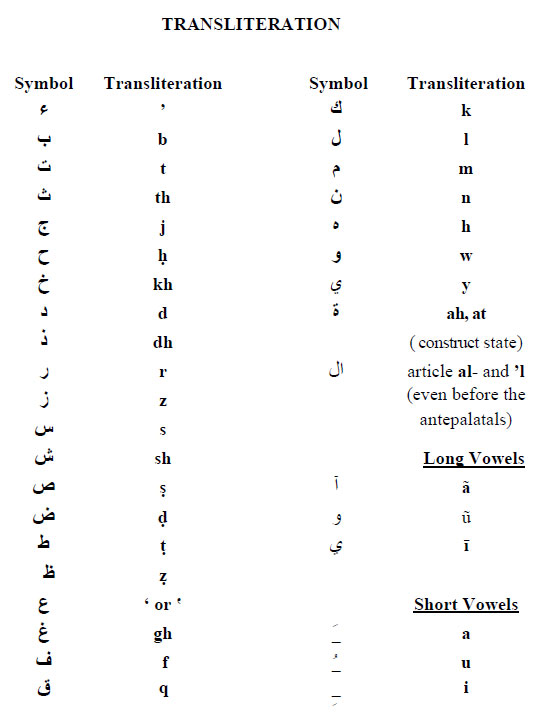

- TRANSLITERATION

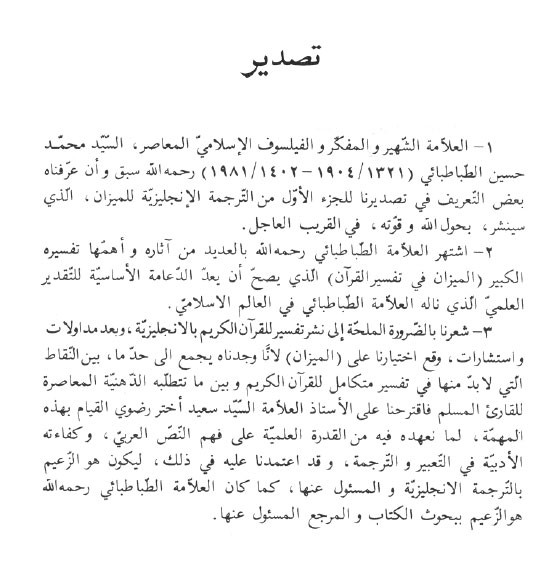

- FOREWORD [IN ARABIC]

- FOREWORD

- Volume 7: Surah Ale-Imran, Verses 121-129

- COMMENTARY

- TRADITIONS

- Volume 7: Surah Ale-Imran, Verses 130-138

- COMMENTARY

- QUR’ĀNIC TEACHING: HOW IT JOINS KNOWLEDGE WITH PRACTICE

- TRADITIONS

- Volume 7: Surah Ale-Imran, Verses 139-148

- COMMENTARY

- TEST AND ITS REALITY

- Volume 7: Surah Ale-Imran, Verses 149-155

- COMMENTARY

- PARDON AND FORGIVENESS IN THE QUR’ĀN

- Volume 7: Ale-Imran, Verses 156-164

- COMMENTARY

- Volume 7: Surah Ale-Imran, Verses 165-171

- COMMENTARY

- Volume 7: Surah Ale-Imran, Verses 172-175

- COMMENTARY

- TRUST IN ALLAH

- TRADITIONS

- THE MARTYRS OF UHUD

- Volume 7: Surah Ale-Imran, Verses 176-180

- COMMENTARY

- It is evident from this verse that: -

- TRADITIONS

- Volume 7: Surah Ale-Imran, Verses 181-189

- COMMENTARY

- TRADITIONS

- Volume 7: Surah Ale-Imran, Verses 190-199

- COMMENTARY

- A COMPARISON BETWEEN THE QUR’ĀN AND THE BIBLE REGARDING TREATMENT OF WOMEN

- TRADITIONS

- Volume 7: Surah Ale-Imran, Verse 200

- COMMENTARY

- A DISCOURSE ON BELIEVERS’ MUTUAL CONNECTION IN ISLAMIC SOCIETY

- 1. Man and Society

- 2. Man and the Growth of his Society

- 3. Islam and the Attention it gives to Society

- 4. Relationship of Individual and Society in the Eyes of Islam

- 5. Is Islamic social System capable of Implementation and Continuation?

- 6. What is the Basis of Islamic Society? How it lives on?

- 7. Two Logics: Logic of Understanding and Logic of Sensuousness

- 8. What is the Meaning of seeking Reward from Allāh, and turning away from others? Someone might ask

- 9. What is the Meaning of Freedom according to Islam?

- 10. What is the Way to Change and Perfection in Islamic Society?

- 11. Is Islamic Sharī‘ah competent to bring happiness in the modern Life?

- 12. Who is entitled to rule over the Islamic Society? What Characteristics he should have?

- 13. The Boundary of Islamic State is Ideology and Belief, not physical Landmarks, nor Man-made Borders

- 14. Islam cares for social Order in all its Aspects

- 15. The true Religion will ultimately prevail over the world

- TRADITIONS

- Volume 7: Surah An-Nisaa, Verse 1

- COMMENTARY

- HOW OLD THE HUMAN SPECIES IS; THE FIRST MAN

- THE PRESENT HUMAN RACE BEGINS WITH ADAM AND HIS WIFE

- MANKIND IS AN INDEPENDENT SPECIES, NOT EVOLVED FROM ANY OTHER SPECIES

- HOW MAN’S SECOND GENERATION PROCREATED

- TRADITIONS

- Volume 7: Surah An-Nisaa, Verses 2-6

- GENERAL COMMENT

- THE ERA OF IGNORANCE

- ISLAM ARRIVES ON THE SCENE

- COMMENTARY

- ALL THE RICHES BELONG TO THE WHOLE MANKIND

- TRADITIONS

- AN ACADEMIC ESSAY IN THREE CHAPTERS

- 1. Marriage is one of the Goals of Nature

- 2. Domination of Males over Females

- 3. Polygamy

- Objections against Polygamy

- ANOTHER RELATED ACADEMIC DISCOURSE ON MANY MARRIAGES OF THE PROPHET

- Volume 7: Surah An-Nisaa, Verses 7-10

- COMMENTARY

- THE DEED RETURNS TO ITS DOER

- TRADITIONS

- NOTES

- DEALT WITH IN THIS VOLUME

- APPENDIX “A”

- APPENDIX “B”