Chapter 1: Origin of Shí'ism: Political or Religious?

1. Introduction

In the polemical writings of the Sunnis, it is asserted that Sunni Islam is the "Orthodox Islam" whereas Shí'ism is a "heretical sect" that began with the purpose of subverting Islam from within. This idea is sometimes expressed by saying that Shí'ism began as a political movement and later on acquired religious emphasis.

This anti-Shí'a attitude is not limited to the writers of the past centuries, even some Sunni writers of the present century have the same views. Names like Abul Hasan 'Ali Nadwi, Manzûr Ahmad Nu'mãni (both of India), Ihsãn Ilãhi Zahír (of Pakistan), Muhibbu 'd-Dín al-Khatíb and Musa Jãr Allãh (both from Middle East) come to mind.

It is not restricted to the circle of those that graduated from religious seminaries and had not been in touch with the so-called academic world. Ahmad Amin (of Egypt) and Fazlur Rahman (of Pakistan) fall in this category.

Ahmad Amin, for example, writes:

"The truth is that Shí'ism is a refuge wherein which everyone who wishes to destroy Islam on account of enmity or envy takes shelter. As such, persons who wish to introduce into Islam the teachings of their Jewish, Christian or Zoroastrian ancestors achieve their nefarious ends under the shelter of this faith."

Fazlur Rahman is an interesting case. After graduating from the Universities of Punjab and Oxford, and teaching at the Universities of Durham and McGill, he worked as the Director of the Central Institute of Islamic Research in Pakistan till 1968. He lost his position as the result of the controversy arising from his view of the Qur'ãn. Then he migrated to the United States and became Professor of Islamic Studies at the University of Chicago. In his famous book, Islam, used as a textbook for undergraduate levels in Western universities, Dr. Fazlur Rahman presents the following interpretation about the origin of Shí'ism:

"After 'Ali's assassination, the Shí'a (party) of 'Ali in Kufa demanded that Caliphate be restored to the house of the ill-fated Caliph. This legitimist claim on behalf of the 'Ali's descendants is the beginning of the Shí'a political doctrine...

"This legitimism, i.e., the doctrine that headship of the Muslim Community rightfully belongs to 'Ali and his descendants, was the hallmark of the original Arab Shí'ism which was purely political...

"Thus, we see that Shí'ism became, in the early history of Islam, a cover for different forces of social and political discontent...But with the shift from the Arab hands to those of non-Arab origin, the original political motivation developed into a religious sect with its own dogma as its theological postulate...Upon this were engrafted old oriental beliefs about Divine light and the new metaphysical setting for this belief was provided by Christian Gnostic Neoplatonic ideas."

He further comments: "This led to the formation of secret sects, and just as Shí'ism served the purposes of the politically ousted, so under its cloak the spiritually displaced began to introduce their old ideas into Islam."

It is in this background that I find it extremely difficult to understand how a learned scholar, from Shí'í background, could echo somewhat similar ideas about the origin of Shí'ism by writing:

"Most of these early discussions on the Imamate took at first sight political form, but eventually the debate encompassed the religious implications of salvation. This is true of all Islamic concepts, since Islam as a religious phenomenon was subsequent to Islam as a political reality."

"From the early days of the civil war in A.D. 656, some Muslims not only thought about the question of leadership in political terms, but also laid religious emphasis on it."

Referring to the support of shi'a of Kufa for the claim of leaders for 'Alids, the learned author writes:

"This support for the leadership of the 'Alids, at least in the beginning, did not imply any religious underpinning...The claim of leadership of the 'Alids became an exaggerated belief expressed in pious terms of the traditions attributed to the Prophet, and only gradually became part of the cardinal doctrine of the Imamate, the pivot on which the complete Shí'ite creed rotates."

After explaining the failures and the martyrdom of the religious leaders who rose against the authorities, he writes:

"This marked the beginnings of the development of a religious emphasis in the role of the 'Alid Imams..."

2. The Beginning of Islam

The Sunnis as well as the Shí'as believe that Islam is primarily a religion whose teachings are not limited to the spiritual realm of human life but also encompass the political aspect of society. Inclusion of political ideals in the religion of Islam does not mean that Islam started or was basically a political movement. Look at the life of Prophet Muhammad (s.a.w.). The Prophet's mission began in Mecca. There is nothing in the pre-hijra program of the Prophet that looks similar to a political movement. It was primarily and fundamentally a religious movement.

Only after the hijra, when the majority of the people of Medina accepted Islam, the opportunity for implementation of Islamic social order arose and so Prophet Muhammad (s.a.w.) also assumed the position of the political leader of the society. He signed agreements with other tribes, sent ambassadors to kings and emperors, organized armies and led Muslim forces, sat in judgement, appointed governors, deputees, commanders, and judges, and he also collected and distributed taxes. Nonetheless, Islam was first a religious movement that later on encompassed political aspects of society. So to say that "Islam as a religious phenomenon was subsequent to Islam as a political reality" is historically an incorrect statement.

3. The Origin of Shí'ism

The origin of Shí'ism is not separate from the origin of Islam since the Prophet himself sowed its seed by proclaiming the wisãya (successorship) and khilãfat (caliphate) of 'Ali bin Abí Tãlib in the first open call to Islam that he made in Mecca.

Islam began when the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him and his progeny) became forty years old. Initially, the mission was kept a secret. Then three years after the advent of Islam, the Prophet was ordered to commence the open declaration of his message. This was the occasion when Almighty Allãh revealed the verse "And warn thy nearest relations." (The Qur'ãn 26:214)

When this verse was revealed, the Prophet organized a feast that is known in history as "Summoning the Family - Da'wat dhu 'l-'Ashira". The Prophet invited about forty men from the Banu Hãshim and asked 'Ali bin Abi Tãlib to make arrangements for the dinner. After having served his guests with food and drinks, but the Prophet wanted to speak to them about Islam, Abu Lahab forestalled him and said, "Your host has long since bewitched you." All the guests dispersed before the Prophet could present his message to them.

The Prophet then invited them the next day. After the feast, he spoke to them, saying:

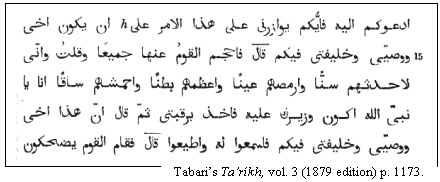

O Sons of 'Abdu 'l-Muttalib! By Allãh, I do not know of any person among the Arabs who has come to his people with better than what I have brought to you. I have brought to you the good of this world and the next, and I have been commanded by the Lord to call you unto Him. Therefore, who amongst you will support me in this matter so that he may be my brother (akhhí), my successor (wasiyyí) and my caliph (khalifatí) among you?

This was the first time that the Prophet openly and publicly called the relations to accept him as the Messenger and Prophet of Allãh; he also uses the words "akhí wa wasiyyí wa khalífatí- my brother, my successor, my caliph" for the person who will aid him in this mission. No one answered him; they all held back except the youngest of them - 'Ali bin Abí Tãlib. He stood up and said, "I will be your helper, O Prophet of God."

The Prophet put his hand on the back of 'Ali's neck and said:

"Inna hadhã akhhí wa wasiyyí wa khalífatí fíkum, fasma'û lahu wa atí'û - Verily this is my brother, my successor, and my caliph amongst you; therefore, listen to him and obey."

This was the first explicit statement because the audience understood the appointment of 'Ali very clearly. Some of them, including Abu Lahab, even joked with Abu Tãlib that your nephew, Muhammad, has ordered you to listen to your son and obey him! At the least, this shows that the appointment of 'Ali bin Abí Tãlib was clear and explicit, not just implied.

After that, the Prophet at various places emphasized the issue of loving his Ahlul Bayt, seeking guidance from them, and drew the attention of the people to the special status that they had in the eyes of God and His Messenger.

Finally, just two months before his death, the Prophet clearly appointed 'Ali in Ghadir Khumm as the leader (religious as well as political) of the Muslims. He said, "Whomsoever's Master I am, this 'Ali is his Master." He also said, "I am leaving two precious things behind, as long as you hold on to them both you will never go astray: the Book of Allãh and my progeny."

A lot has been discussed and written on these events. The reader may refer to the following works in English:

•A Study on the Question of Al-Wilaya by Sayyid Muhammad Bãqir as-Sadr, translated by Dr. P. Haseltine. (This treatise was first translated in India under the appropriate title: "Shí'ism: the Natural Product of Islam".)

•The Origin of Shí'a and Its Principles by Muhammad Husayn Kãshiful Ghitã'.

•Imamate: the Vicegerency of the Prophet by Sayyid Saeed Akhtar Rizvi.

•Origins and Early Development of Shí'a Islam by S. Hussain M. Jafri.

•The Right Path by Syed 'Abdulhussein Sharafuddin al-Musawi.

•"The Meaning & Origin of Shí'ism" by Sayyid Saeed Akhtar Rizvi in The Right Path, vol.1 (Jan-Mar 1993) # 3.

Anyone who reads these materials will see that the beginning of Islam and Shí'ism was at the same time and that, just like Islam, Shí'ism was a religious movement that also encompassed social and political aspects of society. As Dr. Jafri writes,

"When we analyse different possible relations which the religious beliefs and the political constitution in Islam bear to one another, we find the claims and the doctrinal trends of the supporters of 'Ali more inclined towards the religious aspects than the political ones; thus it seems paradoxical that the party whose claims were based chiefly on spiritual and religious considerations, as we shall examine in detail presently, should be traditionally labelled as political in origin."

It is indeed unthinkable that the famous companions of the Prophet like Salmãn al-Fãrsi and Abu Dharr al-Ghifãri thought of 'Ali primarily as a political leader, and only later on started thinking of him as a religious leader also.

In his academic work, Islamic Messianism, the learned scholar counts the civil war as the beginning of "religious Shí'ism": "From the early days of the civil war in A.D. 656, some Muslims not only thought about the question of leadership in political terms, but also laid religious emphasis on it."

But in his article that was presented in a community gathering and published by one of the religious centers, he places the beginning of Shí'ism from the time of Ghadir Khumm. He writes, "The proclamation by the Prophet on that occasion gave rise to the tension between the ideal leadership promoted through the wilaya of Ali ibn Abi Talib and the real one precipitated by human forces to suppress the purposes of Allãh on earth."

This dichotomy between "the academician" and "the believer" is indeed disturbing. May Almighty Allãh grant all workers of the faith the confidence to stand for their faith in all gatherings, of insiders as well as outsiders (fis sirri wa 'l-'alãniyya).

4. The Name "Shí'a"

A follower of Islam is known as "Muslim" whereas a Muslim who believes in Imam 'Ali as the immediate successor and caliph of Prophet Muhammad (s.a.w.) is known as "Shí'a". The term "Shí'a" is a short form of Shí'atu 'Ali - follower of 'Ali".

Muslims take great pride in being affiliated to Prophet Ibrãhím (a.s.), and rightly so. It is also a known fact among Muslims that Prophet Ibrãhím was himself named as a "Muslim" by Almighty Allãh.

"Ibrãhim was neither a Jew nor a Christian but he was a sincere 'Muslim' (one who submits to Allãh), and he was not one of the polytheists." (3:67)

What the people do not notice is that Almighty Allãh has named Prophet Ibrãhím as a "Shí'a" also; of course, not "Shí'a of 'Ali" but "Shí'a of Nûh". He says:

"Peace and salutation be to Nûh in the worlds...and most surely among his followers ('shí'a') is Ibrãhím..." (37:79-83)

So those who call themselves as "Muslims" and "Shí'as" are actually following the tradition established by Almighty Allãh in being called as "followers" of pious believers just as Prophet Ibrãhím has been described as a follower of Prophet Nûh.

* * *

0%

0%

Author: Sayyid Muhammad Rizivi

Author: Sayyid Muhammad Rizivi