CULTURAL ZONES IN ISLAMIC CIVILIZATION

People often speak of Arabic, Persian, or Turkish Islam as if they were three Islams. In reality there is only one Islam, but with local coloring related to the ethnic, linguistic, and cultural traits of the different peoples who became part of the Islamic community. Wherever Islam went, it did not seek to level the existing cultural structures to the ground, but to preserve and transform them as long as they did not oppose the spirit and form of the Islamic revelation. The result was the creation of a single Islamic identity. The vast area of the “Abode of Islam” (dar al-islam

) therefore came to display remarkable diversity on the human plane while reflecting everywhere the one message of the Quran revealed through the Prophet. This cultural and ethnic diversification must therefore be added to all of the factors already mentioned to make clearer the patterns that, superimposed upon each other, have created the great diversity in unity found in Islam.

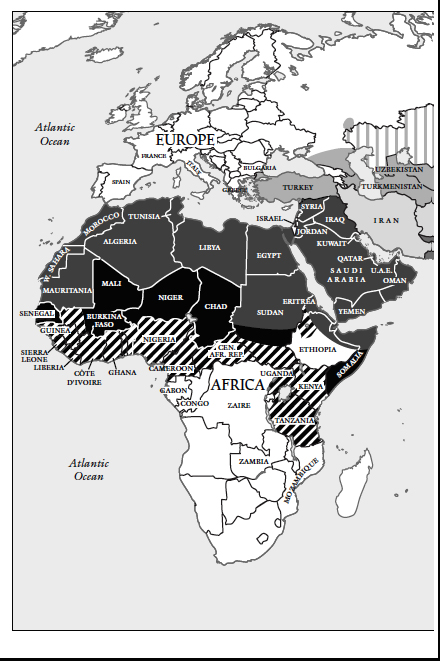

The first cultural zone in the Islamic world is the Arabic zone, which stretches from Iraq and the Persian Gulf to Mauritania and before 1492 into the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula. Needless to say, in contrast to what many in the West think, the Arab world is not by any means synonymous with the Islamic world. In fact, Arab Muslims constitute less than a fifth of all Muslims, being around 220 million in number, but since the Quran was revealed to the Arab Prophet of Islam and the first Islamic society was established in Arabia, the Arabic zone of the “Abode of Islam” is the oldest part of the Islamic community and remains central to it. One of the great mysteries of early Islamic history is that as the Arab armies came out of Arabia, the lands that they conquered to the north and the west became both Islamicized and Arabized. The word “Arab” is a linguistic and not an ethnic term when used in a phrase like “the Arab world.” There was also much Arab migration into this world, but what made it decisively Arab was the adoption of the Arabic language from Morocco to Iraq. Even a country with such an unparalleled ancient past as Egypt became Arab and in fact remains to this day the center of Arabic culture. In contrast, the people of the Persian Empire under the Sassanids, who were conquered by the Arabs in the seventh century, became Muslim, but they did not adopt the Arabic language. Rather, they developed Persian on the basis of earlier Iranian languages and retained a distinct cultural zone of their own. Iraq was the only exception. Although the seat of the Sassanid capital, it became Arab and in fact the center of the ‘Abbasid caliphate, but it always retained strong Persian elements.

It is interesting to compare this development with the spread of Christianity into Europe. Through becoming Christian, Europe also became to some extent a part of the Abrahamic world, but remained less Semiticized than the non-Arab Muslims who embraced Islam, because through St. Paul Christianity itself had already become less “Semitic” before spreading into Europe. That is why the Christianization of Europe was not accompanied by the spread of Aramaic or some other Semitic language in the same way that Arabic spread in the Near East and Africa and also among Persians and Indians, who belonged to the same linguistic and racial stock as the Europeans.

Not only were the Gospels written in Greek and not Aramaic, which Christ spoke, but also the Bible itself was translated early into Latin as the Vulgate and became linguistically severed from its origin. Latin became the closest in its role as the language of religion and learning in the West to what Arabic was in the Islamic world, with the major difference that Arabic is the sacred language of Islam as Hebrew is that of Judaism, whereas Latin is a liturgical language of Christianity along with several other liturgical languages such as Greek and Slavonic. The Arabization of what is now the Arab world and the significance of Arabic among non-Arab Muslims cannot therefore be equated with the Christianization of Europe and the role of Latin in the medieval West, although there are some interesting parallels to be drawn between the two worlds.

The Arabic zone, characterized by the use of Arabic as not only the language of religion, which is common to all Muslims, but also as the language of daily life, is further divided into an eastern and a western part, with the line of demarcation being in the middle of Libya. The western lands, called in classical Arabic al-Maghrib, that is, “the West,” are further divided into the “near West,” including western Libya, Tunisia, and most of Algeria, and “the far West,” including western Algeria, Morocco, Mauritania, and in earlier periods of Islamic history al-Andalus, or Muslim Iberia. Also within the western zone are important non-Arab groups, the most important being the Berber, who inhabit mostly the Atlas Mountains and who have their own distinct language.

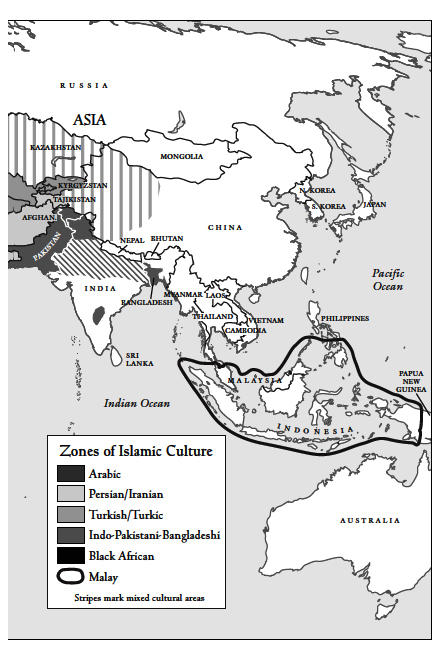

The second zone of Islamic culture, whose people were the second ethnic group to embrace Islam and to participate with the Arabs in building classical Islamic civilization, is the Persian zone, consisting of present-day Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan (with certain cities in Uzbekistan).

The dominant language of the people of all these countries is Persian, known locally by three different names, Farsi, Dari, and Tajik, all of which are the same language; the differences between them are no greater than differences between the English of Australia, England, and Texas. This zone also included southern Caucasia, the old Khorasan, Transoxiana, and parts of what is today Pakistan before the migration south of Turkic people from the tenth and eleventh centuries and subsequent ethnic and geopolitical changes. The people of this zone are predominantly of the Iranian race, which is a branch of the Aryan or Indo-Iranian-European peoples, and Persian is related to the Indo-European languages as are other Iranian languages spoken in this zone, such as Kurdish, Baluchi, and Pashtu.

This zone has a population of some 100 million people, but its influence is felt strongly beyond its borders in other zones of Islamic culture in Asia from the Turkic and the Indian to the Chinese.

The first Persian to embrace Islam was Salman-i Farsi, a slave whom the Prophet caused to become free, making him a member of his “Household.” From the beginning the Persians were deeply respectful of the “Family of the Prophet” and many of the descendants of the Prophet, including the eighth Imam, ‘Ali al-Rid.a, are buried in Persia.

But it would be false to think that the Persians were always Shi‘ites and the Arabs Sunnis. Shi‘ism began among Arabs and in the tenth century

much of the Arab east was Shi‘ite, while Khorasan, a major Persian province, was the seat of Sunni thought. It is only after the establishment of the Safavids that Persia became predominantly Shi‘ite and this majority increased when Afghanistan, a part of Baluchistan, and much of Central Asia, which were predominantly Sunni, were separated from Persia, and Iran in its present form was created. As far as Afghanistan is concerned, during the Safavid period until the eighteenth century it was part of Persia. Then the leader of the Afghan tribes defeated the Safavids and killed the last Safavid king.

Shortly thereafter Nadir Shah, the last oriental conqueror, recaptured lands all the way to Delhi, including what is today Afghanistan. After his death, however, eastern Afghanistan became independent, and in the nineteenth century finally, under British pressure, Persia relinquished its claim on Herat and western Afghanistan, and thereafter Afghanistan as we now know it came into being.

The third zone of Islamic culture is that of Black Africa.

Among the entourage of the Prophet, in addition to Salman, there was another famous companion who was not Arab. He was Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi, the muezzin or caller to prayer of the Prophet, who was a Black African.

His presence symbolized the rapid spread of Islam among the Blacks and the creation of the Black African zone of Islamic culture, encompassing a vast area from the highlands of Ethiopia, where Islam spread already in the seventh century, to Mali and Senegal. The descendants of Bilal are said to have migrated to Mali, forming the Mandinka clan Keita, which helped create the Mali Empire. Some of the companions of the Prophet also migrated to Chad and established Islam there a generation after the Prophet.

Altogether Islam spread in Black Africa mostly through trade, and such tribes as the Sanhaja, who themselves embraced Islam early, became intermediaries between Arab Muslims to the north and Black Africans. By the eleventh century a powerful Islamic kingdom was established in Ghana, and by the fourteenth century the Mali Empire, which was Muslim, was one of the richest in the world; its most famous ruler, Mansa Musa, one of the most notable rulers in the whole of the Islamic world.

In East Africa, which received Islam earlier than West Africa, the process of Islamization took a different path and was influenced greatly by the migration of both Arabs and Persians into the coastal areas of West Africa. By the twelfth century a Swahili kingdom was established with its capital in Kilwa, and from the mixture of Arabic, Persian, and Bantu the new Swahili language, perhaps the most important Islamic language of Muslim Black Africa, was born.

But in contrast to the Arab and Persian worlds, where one language dominates, the Black African zone of Islamic culture consists of many subzones with very distinct languages ranging from Hausa and Fulani to Somali. Some of these languages are also spoken by Christians and are culturally signficant for African Christianity.

Although the north of the African continent was already Arab a century after the rise of Islam, the area called classically the Sudan, which included

the steppes and the grasslands from present-day Sudan to Senegal, also became to a large extent Muslim over a millennium ago. It is, however, only since the nineteenth century that Islam has begun to penetrate inland into the forest regions south of the classical Sudan. There are of course also intermediate regions between the Arabic north and Black Africa where the two zones become intermingled, such as present-day Sudan, Eritrea, and Somalia. The zone of Black African Islamic culture with a population of well over 150 million people is bewilderingly diverse and presents a remarkable panorama of ethnic and cultural diversity within the local unity of Black African culture and the universal unity of Islam itself.

The fourth zone of Islamic culture is the Turkic zone, embracing all the people who speak one of the Altaic languages, of which the most important is Turkish, but which also include Adhari(Azeri)

, Chechen, Uighur, Uzbek, Kirghiz, and Turkeman. The Turkic people, who were originally nomadic, migrated south from the Altai Mountains to conquer Central Asia from the Persians, changing its ethnic nature but remaining culturally very close to the Persian world. By the time they had entered the Persia of that historical period, they had already embraced Islam and in fact became its great champions. Not only did they defeat local Persian rulers such as the Samanids, but they soon pushed westward toward Anatolia, defeating the Byzantine army at the Battle of Manzikert (Malazgirt in Turkish) in 1071. This was one of the pivotal battles of Islamic history. It opened the Anatolian pasturelands to the Turkic nomads and led to the Turkification of Anatolia, the establishment of the Ottoman Empire, and finally to the conquest of Constantinople in 1453. The Turks were powerful militarily and ruled over many Muslim lands, including Persia and Egypt, and their role in later Islamic history can hardly be exaggerated. Today the Turkic peoples, composed of more than 150 million people, are spread from Macedonia to Siberia and all the way to Vladivostok and are geographically the most widespread ethnic and cultural group within the Islamic world. There are notable Turkic groups also within other areas that are not majority Turkic, including Persia, Afghanistan, Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and Russia, which has important Turkic minorities who are remnants of people conquered during the expansion of the Russian Empire under the czars.

The fifth major zone of Islamic culture is that of the Indian subcontinent. Already in the first decade of the eighth century, the army of Muh.ammad ibn Qasim had conquered Sindh, and thus began the penetration of Islam into the subcontinent during the next few centuries, but Islam spread throughout India mostly through Sufi orders.

There were also invasions by various Turkic rulers into India, and from the eleventh century onward and until the British colonization of India Muslim rulers dominated over much of India, especially the north, where the Moghuls established a major empire in the sixteenth century. Indian Islam is ethnically mostly homogeneous, with some Persian and Turkic elements added to the local Indian population, but it is culturally and linguistically very diverse. For nearly a thousand years the intellectual and literary language of Indian Muslims was Persian, but several local languages, such as Sindhi, Gujrati, Punjabi, and Bengali, also gained some

prominence as Islamic languages. Gradually, from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, a new language was born of the wedding of the Indian languages and Persian with Turkic elements added and became known as Urdu.

Written in the Arabic-Persian script, Urdu became, like Swahili, Ottoman Turkish, and several other Islamic languages, a major language of Islamic discourse and was later adopted as the official language of Pakistan. The Indian zone of Islamic culture includes Pakistan, Bangladesh, Muslims of India and Nepal, and the deeply rooted Islamic community of Sri Lanka. There are some 400 million Muslims in this region, more than in any other. The reason for this vast population is the rapid rise of the general population in all of India since the nineteenth century, including both Hindus and Muslims, and the fact that more than one-fourth of Indians had embraced Islam, which was able to provide providentially a path of salvation for those who could no longer function within the world of traditional Hinduism. They have created some of the greatest works of Islamic art and culture, and although ruled often by Turkic dynasties, they have been very close in cultural matters to the Persian world until modern times.

The sixth zone of Islamic culture embraces the Malay world in Southeast Asia. Islamicized by Arab traders from the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea and also by merchants and Sufis from India from the thirteenth century onward, Malay Islam displays again much ethnic homogeneity and possesses local traits all its own. Influenced deeply from the beginning by Sufism, which played a major role in the spread of Islam into that world, Malay Islam has usually reflected a mild and gentle aspect also in conformity with the predominant ethnic characteristics of the people. Dominated by Malay and Javanese languages, Malay Islam embraces Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, and sizable minorities in Thailand as well as the Philippines and smaller minorities in Cambodia and Vietnam. Altogether there are over 220 million Muslims in this zone, and although this part of the Islamic world is a relative newcomer to the “Abode of Islam,” its adherents are known for their close attachment to Mecca and Medina and love for the Prophetic traditions.

As is the case with Africa and India, Malay Islam is highly influenced and colored operatively and intellectually by Sufism.

Besides these six major zones of Islamic culture, a few smaller ones must also be mentioned. One is Chinese Islam, whose origin goes back to the seventh century, when soon after the advent of Islam Muslim merchants settled in Chinese ports such as Canton. There has been a continuous presence of Islam in China since that time, but mostly in Sinkiang, which Muslim geographers call Eastern Turkistan.

The Islamic population of China includes both people of Turkic origin, such as the Uigurs, and native Chinese called Hui. Even among the Hans there are some Muslims. The number of Muslims in China remains a great mystery and figures from 25 to 100 million have been mentioned. There is a distinct Chinese Islamic architecture and calligraphy as well as a whole intellectual tradition closely allied to Persian Sufism. The Islamic

intellectual tradition in China began to express itself in classical Chinese rather than Persian and Arabic only from the seventeenth century onward.

Then there are the European Muslims-not Turkish enclaves found in Bulgaria, Greece, and Macedonia, but European ethnic groups-that have been Muslims for half a millennium. The most important among these groups are the Albanians, found throughout Albania, Kosovo, and Macedonia, and Bosnians, found mostly in Bosnia but to some extent also in Croatia and Serbia. These groups are ethnically of European stock, and the understanding of their culture is important for a better comprehension of both the spectrum of Islam in its totality and the rapport between Islam and the West in today’s Europe.

Finally, there are the new Islamic communities in Europe and America, including both immigrants and converts (or what many Muslims prefer to call reverts, that is, those who have gone back or reverted to the primordial religion, which is identified here with Islam). These include several million North Africans in France, some 3 million Turks and a sizable number of Kurds in Germany, some 2 million mostly from the Indian subcontinent in Great Britain, and smaller but nevertheless sizable populations in other European countries. In America there are both immigrants, mostly from the Arab East, Iran, and the subcontinent, and converts, primarily among African Americans but also some among whites. The spread of Islam among African Americans began with Elijah Muhammad, who created the Nation of Islam, which espouses reverse racism against whites. This movement later split into two groups and most of its members, along with other African American Muslims, soon joined the mainstream of Islam.

In this process the role of El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, better known as Malcolm X, was of particular significance. There are some 25 million Muslims in Europe, some 6 million (although some have claimed other figures ranging from 5 to 7 million) in America, half a million in Canada, and perhaps over 2 million in South America. To view the spectrum of Islam globally, it is necessary to consider also these Islamic communities in the West, especially since they play such an important role as a bridge between the “Abode of Islam” (dar al-islam

), from which they come, and the West, which is their home.

These zones of Islamic culture described briefly here display a bewildering array of ethnicities, languages, forms of

0%

0%

Author: Seyyed Hossein Nasr

Author: Seyyed Hossein Nasr