TRADITIONAL, MODERNIST, AND “FUNDAMENTALIST” INTERPRETATIONS OF ISLAM TODAY

All that has been said thus far provides the necessary context and framework for understanding the recent developments in the Islamic world. Until the impact of European colonialism on the heart of the Islamic world, there were those who fought against Western rule in the extremities of the “Abode of Islam,” but there were no Muslim modernists or fundamentalists. Muslims were all traditional and fitted into the complex pattern of the spectrum of Islam outlined above. But with the advent of European domination of the heartland of Islam, represented by the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt in 1798, the period of diverse reactions and interpretations leading to the contemporary period began.

The European encroachment upon the Islamic world had actually begun over two and a half centuries earlier with the Portuguese and later Dutch and British domination of the Indian Ocean, which had been a major economic lifeline for Islamic civilization. There had also been European invasions of North Africa, the decisive defeat of the Ottoman navy in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, which cut the Ottomans off from the western Mediterranean, and the defeat of the Ottomans in their siege of Vienna in 1683, which marked the beginning of the waning of their power. But none of these events, nor the Dutch colonization of the East Indies, nor British penetration into India, moved the minds and souls of Muslims as did the conquest of Egypt. That event awakened Muslims to a challenge without precedence in their history.

The Quran states, “If God aideth you, no one shall overcome you” (3:159). In the eyes of Muslims, twelve centuries of Islamic history had demonstrated the legitimacy of their claim and the truth of their call. God had been “on their side” and aided them over all those centuries, notwithstanding the defeat of Muslims in Spain and the destruction of the Tartar kingdom by the Russians, because these were at the margins of the world of Islam and lack of internal unity was considered as the reason for these defeats.

Otherwise, wherever Islam had gone, it had become victorious; even the powerful Mongols had soon embraced Islam. But these Europeans, whom Muslims had neglected for so long and considered their cultural inferiors, were now dominating the Islamic world and there was no possibility of their accepting Islam as the Turks or Mongols had. They claimed themselves to be superior and were so proud of their own culture that they showed no interest in anything else. This situation created a crisis of cosmic proportions with eschatological overtones.

Several attitudes could have been taken in face of this crisis, and in fact every one of them was adopted by one group or another. One view held that Muslims had become weak because they had strayed from the original message of the faith and had become corrupted by luxury and deviations.

This was the position of the so-called puritanical reformists, of whom the most famous, the eighteenthcentury Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab from Najd, lived in fact before the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt at the end of the

eighteenth century, but whose message sought to respond to causes for Muslim weakness. Although his message remained mostly in Arabia, this type of puritanical reformism, which was usually against Sufism, Shi‘ism, Islamic philosophy and theology, and the refinement of classical Islamic cities as demonstrated in the arts, became known as the Salafiyyah, that is, those who follow the early predecessors, or salaf, disregarding the thirteen or fourteen centuries of development of the Islamic tradition from its Quranic and Prophetic roots.

A second possibility was to turn to eschatologicalhadiths

concerning the end of the world, when, it was said, oppression would reign everywhere and Muslims would become weakened and dominated by others. As a result of this focus, a wave of Mahdiism swept across some areas of the Islamic world in the early nineteenth century, ranging from the Brelvi movement in the northwestern province of present-day Pakistan; to the movements of Ghulam Ah.mad and the Bab already mentioned; to uprisings by major figures in West Africa, of whom the most significant, although his career began somewhat earlier, was ‘Uthman Dan Fadio, the founder of the Sokoto Caliphate, whose influence spread even to the Caribbean; to the Mahdiist movement of the Sudan, which inflicted the only defeat on the British army in the nineteenth century. As with every millennialist movement, this Mahdiist wave gradually died down, in this case by the second half of the nineteenth century.

The third possibility was to say, in the manner of European modernists, that the regulations of Islam were for the seventh century and times had changed; therefore religion had to be reformed and modernized. The modernists began in Egypt, the most famous of whom were Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, who was of Persian origin, and Muh.ammad ‘Abduh. They also appeared in Ottoman Turkey, especially within the Young Turk movement; in India, with such figures as Sir Sayyid Ah.mad Khan; and in Persia, which produced several other figures besides al-Afghani, whose effect was, however, more local. These modernists varied in their degree of modernism and approach, but in general they were great admirers of the West and of rationalism, nationalism, and modern science. The most philosophical of all of them was Muh.ammad Iqbal, who belongs to the end of this first period of response to the West, which lasted until World War II. When Western scholars speak of Islamic reformers, they have mostly such figures in mind, along with the so-called puritanical reformers. From the ranks of the modernists rose nationalists and liberal thinkers, men who sought to modernize Islamic society, on the one hand, and fight against the West in the name of national independence, on the other. The colonial wars fought against Western powers for national independence by such figures as Ataturk, Sukarno, Bourgiba, and others were carried out in the name of nationalism, not Islam.

Consequently, when Western powers left their colonies, at least outwardly, in many areas they left behind them ruling groups who were Muslim in name, but whose thinking was more like that of the colonizers they had replaced.

There were, of course, also groups of fighters for independence who were not modernists at all, but traditional Muslims, often associated with various Sufi orders. They usually carried out military resistance to preserve their homelands with a degree of nobility and magnanimity that deeply impressed their European enemies. One can cite as a supreme example of this type Amir ‘Abd al-Qadir, the great Algerian freedom fighter and Sufi sage; his opponent, a French general, wrote back to Paris saying that fighting against the Amir was like confronting one of the prophets of the Old Testament. Another notable example is Imam Shamil, who fought for years in Caucasia against Russian encroachment. The example of the saintly nature of these men and the manner in which they treated their enemies as well as noncombatants, no matter what the other side was doing, is of the utmost importance for Muslims as well as Westerners to remember in the present-day situation.

Most of the Islamic world in the period between, let us say, 1800 and World War II did not react in any of the three manners described above. They were the traditional Muslims for whom the life of theShari‘ah

as well as the Tariqah continued in its time-honored manner. There were, of course, continuous renewals from within that must not, however, be confused with reform in its modern sense. Many great scholars of Law continued to appear and Sufism was rejuvenated in several areas, especially in the Maghrib and West and East Africa, as we see in the rise of the Tijaniyyah and Sanusiyyah orders as well as the appearance of such great masters as Shaykh al-Darqawi, Shaykh Ahmad al-‘Alawi, and Shaykh Salamah al-Rad.i, all of whom revived the Shadhiliyyah Order. Nevertheless, the modus vivendi of traditional Muslims was not reaction, but continuation of the traditional Islamic modes of life and thought.

After World War II most Islamic countries had become politically free, except for Algeria, which gained its independence in 1962 after a war that cost a million lives, and Muslim areas within the Communist world. The general population of Muslims had expected that with political independence would come cultural, social, and economic independence as well. When the reverse occurred, that is, when with the advent of political independence Westernized classes began ruling over a deeply pious public, as can be seen in countries as different as Turkey, Iran, Egypt, and Pakistan, major reactions set in that can be seen throughout the Islamic world to this day.

The old modernist and liberal schools of thought became discredited, as did the modernists as a political class, which had failed to solve any of the major problems that society faced in addition to suffering humiliating defeats, especially in the several Arab-Israeli wars. Nevertheless, modernism continued, often with a new Marxist component, and remained powerful because it controlled and still controls the state apparatus in most Muslim lands. But its intellectual and social power began to wane and weaken nearly everywhere except in Turkey, where Ataturk’s secularism remains strong, held in place by the force of the army. Iran was the first country in which a political revolution removed the modernist government in favor of an Islamic one. A process of internal Islamization also took

place, gradually and without revolutionary upheaval, in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Malaysia, the Sudan, Jordan, Egypt, and some other countries, and that process continues.

As for what is called “fundamentalism,” the earlier form of it as found in Saudi Arabia became transformed in many ways. By the 1960s there was a general malaise in the Islamic world caused by the simple emulation of a West, which, according to its leading thinkers, did not know where it was going itself. Many people, even among the modernized classes, turned back to Islam to find solutions to the existential problems posed by life itself and more particularly the actual situation of Muslims. The desire of the vast majority of people was to be left alone to solve the problems of the Islamic world, to preserve the religion of Islam, including the revival of theShari‘ah

, and to rebuild Islamic civilization, but the dominant civilization of the West hardly allowed such a thing to take place. Many organizations were nevertheless established to pursue these ends by peaceful means, chief among them the Ikhwan al-Muslimin, or Muslim Brotherhood, founded in Egypt in the 1920s by H. asan al-Banna’, and the Jama‘at-i islami, founded by Mawlana Mawdudi in 1941, both of which remain powerful to this day.

In the past few decades this desire to preserve religion, re-Islamicize Islamic society, and reconstruct Islamic civilization has drawn a vast spectrum of people into its fold, all of whom are now branded indiscriminately in the West as “fundamentalist.” The majority of such people, however, pursue nonviolent means to achieve their goals, as do most Christian, Jewish, or Hindu “fundamentalists.” But there are also those who take recourse to violent action, nearly always when they are trying to defend their homeland, as in Palestine, Chechnya, Kashmir, Kosovo, or the southern Philippines, or sometimes in exasperation to defend their faith and traditional cultural values, as one sees in occasional violent eruptions in Indonesia, Pakistan, and elsewhere.

But to act Islamically is to act in defense. Those who inflict harm upon the innocent, no matter how just their cause might be, are going against the clear teachings of the Quran and theShari‘ah

concerning peace and war (to which we turn later in Chapter 6). In any case, the unfortunate use of the term “fundamentalism,” drawn originally from American Protestantism, for Islam cannot now be avoided, but it is of the utmost importance to realize that it embraces very different phenomena and must not be confused with the demonizing usage of the term in the Western media.

Disappointment among Muslims with the lack of true freedom after the attainment of political freedom after World War II also led to a new wave of Mahdiism, as seen in the coming of Ayatollah Khomeini to power in Iran at the time of the Iranian Revolution of 1979 (which was a major event in modern history and which definitely possessed eschatological overtones), the taking over of the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1980, and the appearance of Mahdi-like figures in Nigeria during the last two decades.

There is no doubt that there is again a presence of Mahdiism in the air throughout the Islamic world, as there are millennialist expectations among both Jews and Christians today.

As for traditional Islam, in contrast to the first phase of the encounter with the West, from the 1960s onward it began to manifest itself in the public intellectual arena and to challenge both the modernists and the so-called fundamentalists.

Scholars deeply rooted in the Islamic tradition but also well acquainted with the West began to defend the integral Islamic tradition, the Tariqah as well as theShari‘ah

, the intellectual disciplines as well as the traditional arts. At the same time they began in-depth criticism not of Christianity or Judaism, but of secularist modernism, which was first incubated and grew in the West, but later spread to other continents. Such scholars base themselves on the universality of revelation stated in the Quran and seek to reject the substitution of the “kingdom of man” for the “Kingdom of God” as posited by modern secularism. Their criticisms of the modern world have drawn much from Western critics of modernism, rationalism, and scientism, including not only such traditionalists as René Guénon, Frithjof Schuon, Titus Burckhardt, and Martin Lings, but also such well-known European and American critics of the modernist project, including modern science and technology, as Jacques Ellul, Ivan Illich, and Theodore Roszak. The traditional Islamic response began with those trained in Western-style educational organizations, but during the past two decades has come to also include figures from among the class of religious scholars, or ‘ulama’, and traditional Sufis. These scholars and leaders seek to preserve the rhythm of traditional Islamic life as well as its intellectual and spiritual traditions and find natural allies in Judaism and Christianity in confronting the challenges of modern secularism as well as globalization.

The great majority of Muslims today still belong to the traditionalist category and must be distinguished from both secularist modernizers and “fundamentalists,” as the latter term is now used in the Western media. In fact, it would be the greatest error to fail to distinguish the traditionalists from the “fundamentalists” and to include anyone who wishes to preserve the traditional Islamic way of life and thought in the “fundamentalist” category. It would be as if in contemporary Catholicism one were to call Padre Pio and Mother Teresa “fundamentalists” because they insisted on preserving traditional Catholic teachings. It is essential to realize that the notion of extremism implies a center, or median, of the spectrum; phenomena are judged “extreme” according to their distance, on either side, from this designated center. Unfortunately in the Western media today, that center is usually defined as the modernizing elements in Islamic society, and it is forgotten that modernism is itself one of the most fanatical, dogmatic, and extremist ideologies that history has ever seen. It seeks to destroy every other point of view and is completely intolerant toward any Weltanschauung that opposes it, whether it is that of the Native Americans, whose whole world was forcibly crushed by it, or Hinduism, Buddhism, or Islam, or for that matter traditional Christianity or Judaism. Orthodox Jews have as much difficulty resisting the constant assault of modern secularism upon their worldview and religious practices as do Hindus or Muslims. If one is going to speak of “fundamentalism” in religions, then one must include “secularist fundamentalism,” which is no less virulently proselytizing and aggressive

toward anything standing in its way than the most fanatical form of religious “fundamentalism.”

In the case of Islam, there are today certainly religious extremists of different kinds, but they do not define the mainstream, or center, of Islam. That center belongs to traditional Islam. And that center is the one against which one should view fanatical religious extremism, on the one side, and the rabid secularist modernism found in most Islamic countries, but especially in such places as Turkey, Tunisia, and Algeria, on the other. Traditional Islam is not opposed to what the West wishes to do within its own borders, but to the corrosive influences emanating from modern and postmodern Western culture, now associated so much with what is called globalization, that threaten Islamic values, just as they threaten Christian and Jewish values in the West itself. But the philosophy of defense of traditional Islam has always been to keep within the boundaries of Islamic teachings.

Its method of combat has been and remains primarily intellectual and spiritual, and when it has been forced to take recourse to physical action in the form of defense of its home and shelter, its models have been the Amir ‘Abd al-Qadirs and Imam Shamils, not the Reign of Terror of the French Revolution or homegrown models of Che Guevara.

To understand events in the Islamic world today, even the most outrageous and evil actions carried out in the name of Islam, it is necessary to have a context within which to place these actions, in the same way that Westerners are able to place Jonestown, Waco, bombs by the Irish Republican Army, Serbian ethnic cleansing, or the killings carried out by Baruch Goldstein or Rabbi Kahane’s group in context and not to identify them simply with Christianity or Judaism as such. This context can only be provided by looking at the vast spectrum of Islam outlined above. Yes, there are those in the Islamic world today who have taken recourse to military action and violence using modern technology with the supposed aim of ameliorating real or imaginary wrongs and injustices. Considering the history of the recent past, it is hardly surprising that such extremist illicit and morally reprehensible actions by a few using the name of Islam should take place, especially when injustices and suppressions within Islamic societies are added to external ones. Nor does asking why despicable actions take place in the name of Islam by the few and coming to understand the background of these actions in any way condone or excuse them.

The vast majority of Muslims still breathe in a universe in which the Name of God is associated above all with Compassion and Mercy, and they turn to Him in patience even in the midst of the worst tribulations. If it seems that more violence is associated with Islam than with other religions today, it is not due to the fact that there has been no violence elsewhere-think of the Korean and Vietnam wars, the atrocities committed by the Serbs, and the genocide in Rwanda and Burundi. The reason is that Islam is still very strong in Islamic society. Because Islam so pervades the lives of Muslims, all actions, including violent ones, are carried out in the name of Islam, especially since other ideologies such as nationalism and socialism have become so bankrupt.

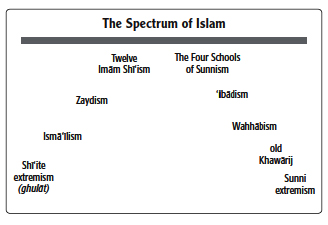

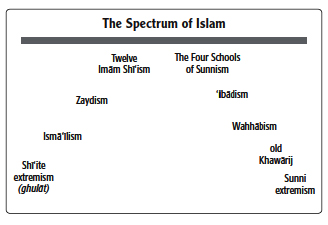

Yet this identification is itself paradoxical because traditional Islam is as much on the side of peace and accord as are traditional Judaism and Christianity. Despite such phenomena, however, if one looks at the extensive panorama of the Islamic spectrum summarized below, it becomes evident that for the vast majority of Muslims, the traditional norms based on peace and openness to others, norms that have governed their lives over the centuries and are opposed to both secularist modernism and “fundamentalism,” are of central concern. And after the dust settles in this tumultuous period of both Islamic and global history, it will be the voice of traditional Islam that will have the final say in the Islamic world.

0%

0%

Author: Seyyed Hossein Nasr

Author: Seyyed Hossein Nasr