Chapter 1: The bourgeois and the official: a historical overview

German literature, in the narrow sense, is the literature of the states, predominantly the Lutheran states, of the Holy Roman Empire, and of their 19th-century successor kingdoms, which were gathered by Bismarck into his Second Empire and, after an interval as the Weimar Republic, formed the core of Hitler’s Third Empire. Austria, though a part of the Holy Roman Empire, can be excluded from this story, as Bismarck excluded it, together with Hungary and Austria’s other, non-Imperial, territories in the Danube basin. Prussia, however, has to be included because of its crucial role in the political defi nition of Germany, even though the duchy, later kingdom, of Prussia (now divided between Poland, the Baltic states, and Russia) was never part of the Empire but was an external power-base for the Electors of Brandenburg, rather like Austria’s Danubian hinterland, and even though Brandenburg-Prussia contributed little of signifi cance to German literature, outside the realm of philosophy, until the 19th century.

The clergy and the university The Lutheranism is important. The Reformation of the early 16th century marks the beginning of German literature, in the sense of the term used here. Not just because the Reformation followed relatively soon (and doubtless not by chance) on the linguistic changes which brought into existence the modern form of the German language, and on the invention of moveable-type printing, which made it desirable, and feasible, to have a standard written language for the whole area across which German books might circulate. By transferring the responsibility for the defence of the Christian faith from the Emperor to the local princes, the Reformation made it possible to imagine a German (Protestant) cultural identity that could do without the Empire altogether, as free of political links to the Roman past as it was of religious links to the Roman present. More, the Reformation launched the individual Protestant states on a voyage towards cultural and political self-suffi ciency even within the German-speaking world. In particular their clergy, then the largest class of the professionally educated and professionally literate, the bearers of cultural values and memory, were cut off from their fellows, even their fellow Protestants, by the boundaries of their state and their historical epoch. They could call only with reservations on the experience of Christians in other places and times and, in practical matters, they had to make their careers in dependence, direct or indirect, on the local monarch. Charged with providing, or supervising, primary education and other charitable activities, such as the care of orphans, which in Catholic states remained the responsibility of relatively independent religious orders or local religious houses, Protestant ministers were often virtually an executive branch of the state civil service.

The instrumentalization of the clergy in the Protestant princely states exercised a profound infl uence on German literature and philosophy because of a peculiarity in Germany’s political and economic development. The towns, mainly Imperial Free Cities, which in the late Middle Ages had been the most dynamic element in German society - centres of commerce, industry, and banking which were also the centres of a richly inventive middle-class culture, especially in the visual arts - went into decline in the century after the Reformation and failed to adjust to Europe’s shift from overland to overseas trade and to the new importance of the maritime nations. Germany’s devastating religious civil war, the Thirty Years War from 1618 to 1648, sealed their fate. In the post-war period only the state powers could raise the capital necessary for reconstruction, and with few exceptions, the great Free Cities decayed into mere ‘home towns’. The princely territories, with their predominantly agricultural economies and rural populations that could be pressed into military service, gained correspondingly in relative power and infl uence. A political revolt of the middle classes, which in 16th-century Holland and 17th-century England was largely successful but which in France went underground with the suppression of the Fronde by the young Louis XIV, was in Germany out of the question. The Empire became a federation of increasingly absolute monarchs who in cultural as in political matters looked to the France of the Sun King as their model. The courtly arts, such as architecture and opera, dedicated to the entertainment and glorifi cation of the prince and his entourage, did well, but printed books were predominantly academic (so often in Latin) or, if they were intended to circulate more widely among the depressed middle classes, were either trivial fantasies, without social or political signifi cance, or works of religious devotion commending contentment with one’s lot. One institution, however, of the greatest importance to the middle class, which after the middle of the 17th century fl ourished better in Germany than elsewhere in Europe, was the university. At a time when England made do with two universities, Germany, with only four or fi ve times the population, had around 40. The university had come late to the German lands - the fi rst was at Prague in 1348 - but in the post-Reformation world it had a quite new signifi cance. The absolute, princely state, with its ambition to control everything, needed offi cers to carry its will into every part of its domains, and these the university provided, principally, until the later 18th century, by training the clergy. Practical subjects, such as fi nance and agriculture, were also taught, and much earlier in Germany than in England, but always with a view to their utility in the state administration. The offspring of well-to-do professionals could afford to study law and medicine and rely on family connections to fi nd them a billet, but for an able young man from a poor background the theology faculty, much the largest and most richly endowed, offered the best prospects of social advancement and future employment.

The 18th-century crisis Eighteenth-century Germany was a stagnant society in which economic and political power was largely concentrated in the hands of the state, and intellectual life was initially in the grip of the state churches. There was little room for private enterprise, material or cultural. Yet this society experienced a literary and philosophical explosion, the consequences of which are still with us. The constriction itself put up the boiler pressure. In England and France there was a signifi cant property-owning middle class, a bourgeoisie in the full sense of the word, able to fi nd an outlet for its capital and its energies in trade and industry, emigration and empire, and eventually in political revolution and reform. In Germany the equivalent class was proportionally much smaller and shut away in the towns, where it could engage in political or economic activity of only local importance. What Germany had in abundance was a class of state officials (and of Protestant clergymen who were state officials by another name), who were close to political power, and were often its executive arm, but who could not exercise it in their own right, and could only look on enviously at the achievements of their counterparts in England, Holland, or Switzerland, or, after 1789, in France:

‘They do the deeds, and we translate the narrations of them into German’, wrote one of them. The only outlet for the energies of this peculiarly German middle class was the book. Germany in the 18th century had more writers per head than anywhere else in Europe, roughly one for every 5,000 of the entire population.

Its fi rst industrial capitalists, its only private entrepreneurs who before 1800 were mass-producing goods for a mass market, were its publishers. In the middle of the 18th century Germany’s official class entered a crisis. The Seven Years War (1756-63) defi nitively established Prussia as the dominant Protestant power in the Empire and, on the continent of Europe, a counterweight to Catholic Austria, while Prussia’s ally, England, emerged similarly victorious on the world stage in the race for colonies at the expense of its Catholic rival, France. Yet at this moment when - at least from a German point of view - Anglo-German Protestantism seemed to have demonstrated its superiority in all respects over Europe’s Catholic South, the religious heart of the cultural alliance began to succumb to an enemy within. Under the name of Enlightenment, the deist and historicist critique of Christianity, which had originated largely in England, began to detach Germany’s theologically educated elite from the faith of their fathers. Since there was not much of a private sector in which an ex-cleric could seek alternative employment, and since loyalty to the state church was something of a touchstone for loyalty to the state itself, a crisis of conscience was an existential crisis too. The struggle for a way out was a matter of intellectual and sometimes personal life and death. Two generations of unprecedented mental exertion and suffering within the pressure-vessel of the German state brought into existence some of the most characteristic features of modern culture, which elsewhere took much longer to develop.

Two routes led out of the crisis, one considerably more secure than the other. First, it was possible to adapt Germany’s most distinctive state institution, the university, to meet the new need.

New career paths, inside and outside academic life, became available for those with a scholarly bent but a distaste for theology, through the creation of new subjects of study or the expansion of previously minor options. Classical philology, modern history, languages and literatures, the history of art, the natural sciences, education itself, and, perhaps most infl uential of all, idealist philosophy - in these new or newly signifi cant university disciplines 18th and early 19th-century Germany established a pre-eminence which, in some cases, has lasted into the present.

Second, and more precariously, the ex-theologian could turn to the one area of private enterprise and commercial activity readily accessible to him: the book market. It has been calculated that, even excluding philosophers, 120 major literary fi gures writing in German and born between 1676 and 1804 had either studied theology or were the children of Protestant pastors. But there was a snare concealed behind the lure of literature. To make money a book had to circulate widely among the middle classes, the professionals and business people, and their wives and daughters, not just among the officials. But these were the classes that the political constitution of absolutist Germany excluded from power and infl uence. It was not therefore possible to write about the real forces shaping German life and at the same time to write about something familiar and important to a wide readership. The price of success was triviality and falsifi cation; if you were seriously devoted to real issues you would stay esoteric, and poor. The German literary revival of the 18th century was in great measure the attempt, fuelled by secularization, to resolve this dilemma.

Especially in the earlier phases it seemed that the example of England, the ally in Protestantism, might be the answer, and hopes of a German equivalent to the English realistic novel, at once truthful and popular, ran high. But Germany could not model its literature on that of England’s self-confi dent and largely self-governing capitalist middle class. Its social and economic starting point was different, and it had to fi nd its own way.

In Germany, political power and cultural infl uence were concentrated in absolute rulers and their immediate entourage, loosely termed the ‘courts’. The interface between these centres and the rest of society, and specifi cally the groups that made up the reading public, was provided by the state officials.

Therefore, the class of officials - those who belonged to it, those who were educated for it, and those who sought access to it - formed the growth zone for the German national literature.

In material terms, a state salary, whether a cleric’s, a professor’s, or an administrator’s, or even just a personal pension from the monarch, provided a foundation so that a literary career, albeit part-time, was at least possible and did not have to be a relentless chase after maximal earnings. In intellectual terms, the writers’ proximity to power, and to the state institutions, meant that the issues they raised in the symbolic medium of literature were genuinely central to the national life and identity, even if their perspective was that of non-participants. The public literary genre which most precisely reflected the ambiguous realities of life in the growth zone, and which, towards the end of the century, reached a point of perfection subsequently recognized as ‘classical’, was the poetic drama, the drama which, though performable and performed, was most widely distributed and appreciated as a printed book. The dramatic form reflected the political and cultural dominance of the princely court, for none of Germany’s many theatres were purely commercial undertakings, all required some kind of state subsidy, and even in the Revolutionary period most still served their original and principal function of entertaining the ruler. Circulation as a book, however, as Germany’s equivalent of a novel, both truthful and commercially successful, reflected the aspiration of the middle classes to a market-based culture of their own. And, fi nally, the philosophical, if not explicitly theological, tenor of the themes of these plays reflected the secularization of Lutheranism which was providing a new vocabulary for the description of personal and social existence, whether by playwrights in the state theatres or by professors in the state universities. Among the most important elements in this new vocabulary were the concepts of moral (rather than political) ‘freedom’ and of ‘Art’, as the realm of human experience in which this freedom was made visible. The German ‘classical’ era gave to the world not only the meaning of the word ‘Art’ which enabled Oscar Wilde to say nearly a hundred years later that it was quite useless, but also the belief that literature was primarily ‘Art’ (rather than, say, a means of communication).

The rise of bourgeois Germany ‘Germany’ around 1800 was not so much a geographical as a literary expression. The most powerful impetus to give it a political meaning probably came from Napoleon. He imposed the abolition of the ecclesiastical territories, a radical reduction in the number of the principalities from over 300 to about 40, and the organization of the remainder into a federation of sovereign states, even before the formal dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. His annihilating defeat of Prussia in the same year forced on it a programme of modernization which was to determine German social and political structures for the next century and a half. The modernization did not, however, take the republican form it had taken in France, and though constitutionalism briefl y fl ourished when it was necessary to rouse the people to throw off the Napoleonic yoke from the necks of their princes, it was abandoned after the Carlsbad Decrees of 1819 which turned Germany, until 1848, into a confederation of police states. The Prussian commercial, industrial, and professional middle classes were still too weak to challenge the king, or even the landowning nobility (the Junkers), and introduce representative government or a separation of legislature and executive. Instead the successful bid for power came from the king’s officials, and the autocratic absolutism of the 18th century gave way to the bureaucratic absolutism of the 19th - a rule of law, free of conscious corruption and directed to the common welfare, but imposing a military level of discipline on all layers of society. The king’s personal decisions remained fi nal, but they were increasingly mediated, and so to some extent checked, by his civil and armed services, into which the nobility were gradually absorbed - partly as a brake on the ambitions of the middle class. The new Prussia, the largest and most powerful of the German Protestant states, had an altogether new signifi cance for its fellows, once the old Imperial framework had vanished.

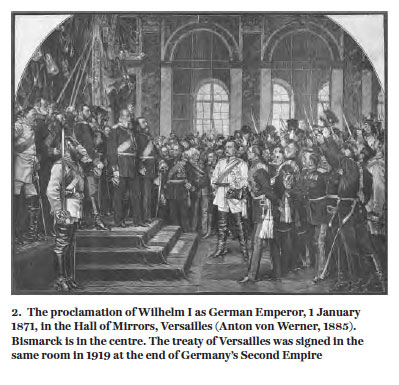

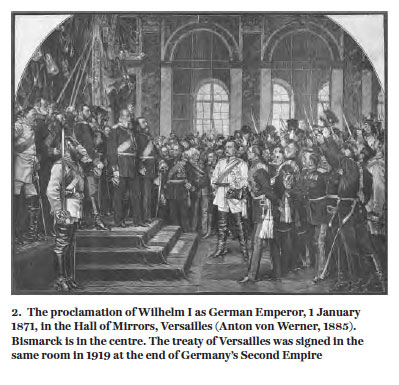

Territories which before 1806 could pass as constituent parts of a larger whole, however ramshackle and loosely defi ned, now had to justify themselves as economically and politically self-suffi cient states, a task to which none of them, apart from Prussia, Austria, and perhaps Bavaria, could pretend to be equal. Some kind of association between them had to be found. There was a supine intergovernmental ‘Federation’ dominated by Austria and a much more effective Customs Union (Zollverein) of a smaller number of territories grouped round Prussia, but the word ‘Germany’ now meant something future and unreal. If it had once referred to the Empire and any other territories attached to the Empire in which German was spoken and written, now it meant the political unit in which all, or most, German-speakers would fi nd their home. And there was the rub: who precisely was to be included in this future Germany? It could hardly contain both Prussia and Austria, as the old Empire and the new Federation were able, more or less, to contain them - though there were many dreamers to whom this seemed possible, among them the author of ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles’ - but equally it could hardly exclude them, given their infl uence over the smaller states and frequent interventions in their affairs. In practice, the two great powers were resolving the issue for themselves: Prussia was expanding purposefully westwards to the Rhineland, while Austria was withdrawing from German affairs to concentrate on its non-German-speaking territories in Eastern Europe and North Italy. In the end, the Protestant intellectuals of Northern Germany, still held together, as under the old regime, by the publishing industry and the university network, threw in their lot with Prussia. After a decade of increasing agitation, 1848, Europe’s ‘year of revolutions’, saw the summoning of the Frankfurt Parliament, a quarter of whose membership was made up of academics, clergy, and writers, and which in 1849 offered the Prussian monarch the kingship of a Germany without Austria. Friedrich Wilhelm IV refused to rule by the free choice of his subjects - ‘to pick up a crown from the gutter’ - though his brother, Wilhelm I, accepted the same ‘lesser German’ (kleindeutsch) crown when Bismarck secured it for him by force of arms in 1866-71.

To the extent to which it was a revolution of professors, and perhaps rather further, the failed German revolution of 1848 was a revolution of the officials, the last act, and the fi nest hour, of the 18th-century reading public. It was an attempt to unify Germany by constitutional and administrative means, while retaining for government, and monarchical government at that, the leading role in the structuring of society. But the balance of power in the German middle class was already beginning to shift fundamentally. Between 1815 and 1848 the population grew by 60%, and as poverty intensifi ed the need for employment grew desperate. After some tentative, state-sponsored beginnings in the 1830s, a fi rst wave of industrialization was felt in the 1840s, with huge (often foreign) investments in a railway network, mainly within the Customs Union, and a consequent economic upswing.

The decade ended with an economic as well as a political crash, and with the last of the pre-industrial famines (partly caused by the same potato blight that devastated Ireland) - factors that together led (as in Ireland) to a surge in emigration. But in the following 20 years Prussia, governed from 1862 by Bismarck, embraced economic liberalism as a means of sweeping away historic and institutional obstacles to the unifi cation of its heterogeneous territories, and the long period of intensive growth began which was to transform Germany into an industrial giant.

As a result, when the Second German Empire was founded in 1871 it had a bourgeoisie, a property-owning and money-making class, which was much larger, wealthier, and more signifi cant for the common good than anything the First Empire had known. The consequences for literature and philosophy were far-reaching. As this class emerged, it battled for self-respect and cultural identity with the long-established middle-class instruments of state power, the officials. The revived bourgeoisie had a more obvious interest in the economic and political unifi cation of Germany than civil servants who owed their positions to the multiplication of power centres, and entry to it was not dependent on passage through the universities. In the early years of the 19th century its frustrated political ambitions expressed themselves, particularly in Prussia, in the literature of escape known as ‘Romanticism’, but as it gained in confi dence its literary culture took on a more explicitly revolutionary, anti-official colour - though the oppositional stance betrayed a continuing dependence on what was being opposed. After the humiliation of official Germany at Frankfurt, however, with industry and commerce fl ourishing in the sunshine of state approval, any sense of inferiority passed, the icons of the previous century were cheerfully ridiculed, literature itself became a paying concern as copyright became enforceable, and novels and plays with such strictly bourgeois themes as money, materialism, and social justice emerged from the realm of the trivial and, for a while, linked Germany’s written culture with that of its neighbours in Western Europe. The uniquely - for the outside world perhaps impenetrably - German culture of the late 18th-century Golden Age, scholarly, humanist, cosmopolitan, survived under the patronage of the lesser courts, in the lee of political events and economic changes, until 1848, but thereafter it declined into academicism or, in the case of the kings of Bavaria, into eccentricity. But though the official class had lost supremacy, it had not lost power, and through the universities, despite the growth of private cultural societies and foundations, it remained the guardian of the national past. As the redefi nition of the German state came to preoccupy all minds, so the servants of the state were able to retain for themselves a certain authority and the two main factions in the middle class sank their differences in the national interest. The concept of ‘Bildung’, meaning both ‘culture’ and ‘education’, was the ideological medium in which this fusion could take place, the value on which all could agree, precisely because it left carefully ambiguous whether you achieved ‘Bildung’ by going to university or simply by reading, or at any rate approving, the right books. The term ‘Bildungsbürger’ gained a currency at this time which it has never since lost. Suggesting a middle class united by its experience of ‘Bildung’, its main function is to identify the official with the bourgeois, to create a community of interest between salaried servants of the state and tradesmen, property owners, and self-employed professionals. A crucial step in the defi nition of ‘Bildung’ was the canonizing of the literary achievements of the official class as ‘classical’. Germany in 1871 was not only to be a nation like England or France - it was to have its literary classics like them too.

In Bismarck’s new Germany the bourgeoisie was accommodated, but kept on a short lead. It was given a voice in the Reichstag, the Imperial Diet, and the lesser representative assemblies of the constituent states, but the executive, with the Imperial Chancellor at its head, was in no formal way responsible to these parliaments.

In practice, of course, the Chancellor needed their co-operation to secure his legislative programme and so officialdom lost the almost absolute power it had enjoyed in the earlier part of the century. But the dominant model for a society in which military service was compulsory was provided by the army (with the upper ranks reserved for the nobility), and Bismarck and his successors treated all attempts to establish parliamentary accountability as insubordination: the socialist party was virtually proscribed for over a decade. Within the constraints imposed by the supreme priority of national unity, the agents of autocracy continued to look down on those they regarded as self-interested individualists and materialists because they made money for themselves, rather than receiving a salary from the state. In the world of ‘Bildung’

too the profession of a shared devotion to the national tradition papered over the deep animosity between those who wrote for a living and the university intellectuals whose literary activity was now largely confi ned to historical and critical study. Like Bismarck, the professor of ‘Germanistics’ - as it was beginning to be called - had as little taste for the bourgeois as for the socialists, Catholics, Jews, or women who were now unfortunately as likely as the bourgeois to involve themselves in the national literature.

In the turmoil of 1848-9, a little-noticed pamphlet, drafted by a German philosopher for a tiny group of English radicals, and with the title of The Communist Manifesto, had prophesied that the free markets aspired to by the national bourgeoisies would grow into a global market, a ‘Weltmarkt’. By the 1870s that prophecy was clearly coming true. Germany’s fi rst experience of globalization was painful, however. The worldwide stock-market crash of 1873, which began in Vienna, led to a long depression from which the world did not emerge until the 1890s. In Germany the depression was relatively shallow and some growth continued, though in the 1880s net emigration (which had totalled 3 million over the previous four decades) reached an all-time high of 1.3 million - a fi gure which is itself a measure of the intensity of globalization. In 1879 Bismarck was moved by the effect of cheap American grain imports on the incomes of the land-owning Junkers to listen to the growing demands for protection from other quarters as well, particularly the heavy industry that would be of strategic importance in wartime, and to abandon his earlier policy of free trade, erecting a tariff wall round his new state. At the same time, he put an end to his ‘cultural war’ (Kulturkampf) with the Catholic Church and endeavoured to outfl ank the working-class movement by introducing Europe’s fi rst system of social security. His motives in establishing ‘state socialism’, as it was soon called, were no different from those that had guided him earlier, and which had deep roots in the German past: first, the overriding need for unity in the state and, second, the interests of the agricultural nobility which continued to furnish Prussia with its ruling class. But the protectionist course on which Germany and the other European states now embarked, and which was eventually adopted even by Britain, long the staunchest advocate, and greatest benefi ciary, of free trade, accentuated the division of Europe, and the world, into would-be autarkic blocs.

Thanks to the inability of politicians, of any country, to imagine an international institutional order which would accommodate to each other the competing energies of numerous growing economies, the developed states, whether empires, federations, or unitary nations, set out to achieve economic and political - that is, military - self-suffi ciency. Germany’s bid for colonies in Africa and the South Seas, which began in 1884, was not so much a serious geopolitical move as a symbolic irritant. Like the huge expansion of the navy, it was a declaration that Germany was anyone’s equal and could look after itself. As general growth resumed in the 1890s it became clear that, with its armed forces backed by the largest chemical and electrical industries in the world, and a coal and steel industry that was catching up on the British, Germany was capable, not necessarily of displacing the British Empire, but certainly of disputing its power to impose its own will. A British hegemony was giving way to a bi-polar world, and from the turn of the century something like a Cold War began in the cultural sphere. Britain turned away from the German models, particularly in philosophy and scholarship, which had had great prestige since the days of the Prince Consort, while voices in Germany emphasized the uniqueness of German literary, musical, and philosophical achievements and the need to protect ‘Kultur’ (the creation of the official classes) from contamination by the materialistic and journalistic (that is, bourgeois) ‘civilization’

of the West. The fusion of disparate elements in the concept of the ‘Bildungsbürger’, though rejected by some of the most clear-sighted critics of the Second Empire, was sustained by projecting its tensions outwards on to the relations between nations and defi ning a unique role for the new Germany. Britain and France at this time wove similar myths of their own special mission in world-history. Tariff walls became walls in the mind, and the mental effects were as serious as the economic distortions which put increasing strains on the inadequate international political order. After more than a decade of toying by the nations of Europe with fantasies of their own exceptionality, in 1914 the war-games went real.

The officials strike back Globalization spelled the end of the bourgeoisie, in the strict sense, and not only in Germany. A class living solely off its capital, off the alienated labour of others, was sustainable only by societies with open frontiers, with open spaces into which the disadvantaged and disaffected could expand. As the world economy grew into a single closed system, and as societies that shrank from the challenge of the political co-operation required by economic integration sought - in vain, of course - to seal themselves off in smaller units, so there was less and less room for a leisured capitalist class, and it was forced increasingly into work. The intrusion of work into the world of capital was reflected, in the fi rst decades of the 20th century, in an intellectual upheaval which broke apart the forms and conventions of the earlier stages of cultural modernity and was at least as violent in Germany and Austria as anywhere else. In literature, art, music, philosophy, and psychology, the concepts of identity, collective and personal, that had been appropriate to an age when the world was wide, and economic expansion was untrammelled by political institutions, were subjected to intense and hostile scrutiny. It was Germany’s misfortune that the representatives of the bourgeoisie achieved the political autonomy, and even supremacy, for which they had been struggling for well over half a century, only when their social and economic and even their cultural position was fatally undermined. In 1918 Germany had its revolution at last. But the new republic was born in military defeat and shackled at once by an unequal peace. It was shorn, not only of its symbolic overseas empire, but of much of its mineral wealth in the territories returned to France and the resurrected Poland. Its middle class, which had grown into prosperity over the previous two generations, was pauperized in the terrible infl ations which reflected the lack of confi dence in its future, and, with the loss of their capital, many private foundations and charities, old and new, ceased to exist. Its rivals, cushioned for a while yet by empire, and by the complacency of victory, could afford to ignore the challenge to their identity implicit in the global market. But Germany and Austria, friendless and unsupported by the labour of subject peoples, had to make their way back to prosperity by their own efforts, as the world’s fi rst post-imperial, and postbourgeois, nations. The culture of the German and Austrian successor-states in the age of the Weimar Republic had about it a radical modernity, indeed postmodernity, whose full relevance to the condition of the rest of the world became apparent only after 1989.

In one crucial respect, however, the Weimar Republic had not been released from its past. The German bourgeoisie might have been reduced to a few super-rich families heading the vertically integrated industrial and banking cartels that had prospered in the days of Bismarck’s ‘state socialism’. But the other component of the middle class, the officials (including the professorate), had survived the debacle remarkably unscathed. The authoritarian monarch had gone, but the state apparatus remained, and its instinct was either to serve authority, or to embody it. The army, the academy, and the administration hankered after their king. They were ill at ease with parliamentary institutions that bestowed the authority of the state on a proletarianized mass society - that is, a society based not on the ownership of land, or even of capital, but on the need and obligation to work. The representative bodies of the Second Empire, crudely divided between nationalists and socialists, had been, largely, a sham and, once the monarchy that was the reason for their existence had passed away, they could not be grown on as a native democratic tradition. Nor was there any obvious external source of democratic inspiration. For nationalists there was no reason to look kindly on the liberal traditions of the victor powers, who hypocritically imposed self-determination on Poles and Czechs, in order to break up Germany and Austria, but withheld it from Indians and Africans, in order to preserve their own empires. To socialists it seemed more important that communist Russia had correctly identifi ed the proletarian nature of modern society than that it was maintaining and extending the brutal Tsarist regime of social discipline. In the absence of native republican models, and with the Prussian inheritance still obscuring the view back to the Holy Roman Empire, the continuing identity of ‘Germany’ was largely guaranteed by the persistence of the official class and its ideology of apolitical ‘Bildung’. The ideology, however, diverted all but the most perceptive writers from the task of defending the constitution. On the one hand, any number of new theories of ‘art’ provided as many reasons for dismissing contemporary politics as superfi cial or inauthentic. On the other, the acceptance of political engagement could lead to a general rejection of conventional ‘culture’ and a coarse anti-intellectualism. The Weimar Republic was betrayed on all sides, and if the writers and artists, on the whole, betrayed it from the left, the public service, including the professors, betrayed it, massively and effectively, from the right. The National Socialist German Workers’ Party presented itself, like ‘state socialism’, as above the distinction between left and right, as the party of national unity in the new age of work, but its appeal was unambiguously that of nostalgia for the authoritarianism decapitated in 1918. Its opportunity came when the excitement of global recovery in the 1920s faltered and, after the great crash of 1929, gave way to global depression. The disastrous decision of the Western nations to respond to this crisis with protectionism took in Germany in 1933 the form of electing a government committed to withdrawing the country from all international institutions and establishing in the economy, as in the whole of society, a command structure based on a military model - a queerly deranged memory of the Second Empire.

In the Third Empire, however, there was none of Bismarck’s subtle accommodation with bourgeois free enterprise. It was the period of officialdom’s greatest and most cancerous expansion, as new layers of uniformed bureaucrats were imposed on old in a permanent revolution generating permanent turf wars, and all the while new, malign, and irrational policies were executed with the same humdrum effi ciency or ineffi ciency as ever and the traditions of Frederick the Great and the 19th-century reformers terminated in Eichmann and the camp commandants who played Schubert at the end of a day’s work. By this stage, however, the culture of the German official class had ceased to be productive and was almost entirely passive. The universities, emptied of anyone of independent mind or Jewish descent, lost their global pre-eminence for ever. The agitprop generated by the ‘Ministry of Popular Enlightenment’ in the form of fi lms, pulp fi ction, or public art is of interest now only to the historical sociologist.

Music and the performing arts were parasitic on the achievements of the past, which by and large they caricatured. The free and creative literary spirits, whether or not they had had official positions, were nearly all either dead or in an exile which they found very diffi cult to relate to their experience of Germany’s past or its present. The professors of philosophy and ‘Germanistics’

who stayed behind devoted themselves at best to relatively harmless editorial projects. Of the worst it is still impossible to speak with moderation.

The bourgeois and the official After zero hour After 1871, 1918, and 1933, the fourth redefi nition of Germany within a lifetime began in 1945. Territorially the adjustment was the biggest there had ever been. Millions moved westwards from areas that had had majority German populations for centuries. The state of Prussia was formally dissolved. Germany was returned approximately to the boundaries of the Holy Roman Empire (without Austria) at the time of the Reformation.

Socially and politically too the zones occupied by Britain, France, and the USA recovered something of 16th-century Germany, before the rise of absolutism: a federal republic, with a Catholic majority, dominated by the industrial, commercial, and fi nancial power of several great towns. Hitler had succeeded where all previous German revolutionaries had failed: he had made Germany into a classless society. For 12 years inherited wealth and station had counted for nothing; what mattered was race, party membership, and military rank. After the destruction, and self-destruction, of his absolutist regime the West German Bonn Republic began from a base of social equality unprecedented in the nation’s history. But the foundation had been laid by Hitler’s ‘party of the workers’ and thanks to the relatively rapid withdrawal of the occupying powers in the West the Federal Republic had from an early stage to confront, from its own resources, the question posed by its continuity with the immediate German past. At fi rst the confrontation, in the public mind, took the form of a creative denial, the energetic construction of an alternative Germany, west-facing, republican, committed to free markets and European integration, and in economic terms highly successful. Culturally, however, the underlying continuity betrayed itself in a troubled relationship with the remoter past of the nation. The literary and philosophical achievements of the period around 1800 still enjoyed their Second Empire status of ‘classics’, but they were stylized and reinterpreted as an ‘other Germany’ of the mind from which, in some mysterious and fateful process, the Germany of 1871-1945

had become detached. To claim, however, that the Federal Republic had recovered that ‘other Germany’ - and the claim was implicit in the decision to call its cultural missions ‘Goethe Institutes’ - was to make the improbable claim that it somehow reincarnated the world of the late 18th-century principalities.

The local German dialectic between bourgeois and official which created the literary culture of that era was at an end.

The relentless advance of the global market had destroyed both parties: the European bourgeoisie was no more, swallowed up in the tide of proletarianization which has turned us all into consumer-producers for the mass market; officialdom had lost its privileged relationship to the national identity with the decline in signifi cance of the nation-state and of the local centre of political power. Both the re-canonization of the classics and the contestation of their authority by critics who felt themselves suffi ciently unimplicated in the German past to sit in judgement on it were failures to assess realistically the historical process in which the 18th-century literary revival, the rise and fall of German nationalism, and the emergence of the new republican Germany were all equally involved. The Russian zone of occupation, from 1949 the German Democratic Republic, was the site of unrealism’s last stand. Here, as elsewhere behind the Wall - surely the ultimate tariff barrier - officialdom for 40 years enjoyed an Indian summer, in seamless real continuity with the previous regime of malignant bureaucracy but in total mental and emotional denial of any resemblance to it. Eastern Germany, in physical possession of many of the cultural storehouses of Bismarck’s Prussia-centred Empire, claimed to be the only true inheritor of what the Second Empire had defi ned as ‘classical’ - though it implausibly represented the ‘other Germany’ as a great materialist tradition culminating in Marx, Engels, and the Socialist Unity Party. With some vacillations, which recall similar uncertainties in Hitler’s cultural policy, this party line was maintained in theatres, museums, and the educational system. With far greater rigour than in the West, therefore, any interrogation of the present which threatened to reveal its affi nities with the Germany of 1933-45

was suppressed, and the appalling crimes of that period were dismissed as somebody else’s affair.

So it was left at fi rst to relatively isolated writers and thinkers in the Federal Republic to begin defi ning an identity for the new Germany by remembering the nightmares from which it had awoken. Official memory, in what was left of the university system, struggled, on the whole unsuccessfully, to recover the literature of the previous two centuries as a living tradition. But poets and novelists and writers for radio, supported by a market eager for books, turned, with rather more effect, to the even more intractable task of relating private consciousness to the world-historical disasters that Germany had both infl icted and suffered, and gradually gained recognition outside Germany too.

As the emigrant generation of the 1930s reached maturity, and as universities on either side of the Atlantic came to exchange personnel more freely, it also came to be appreciated in the wider world that German philosophy and critical theory still provided essential instruments for understanding the revolutionary changes of the 20th century, especially if they were allowed to interact with ideas from the English-speaking cultures. After 1968

some of these international developments accelerated, partly as a result of intensive French engagement with German thinkers, but Germany itself found it more diffi cult to move forward, perhaps because the rewards of a generation’s reconstructive efforts were at last being enjoyed. The universities, transformed into institutions of mass education, fi nally lost their privileged position in the nation’s intellectual life except perhaps in the area in which they had begun, Protestant theology. An affl uent social security system took the sting of practical urgency out of domestic moral and political issues, whatever theoretical heat they generated.

Above all, the gravitational fi eld of the Democratic Republic pulled all left-wing thinking out of true, creating the illusion of a political alternative even when the regime was universally acknowledged to have lost all credit, spuriously reviving the attractions of ideas obsolete since 1918, such as authoritarian state socialism and German isolationism, and obscuring the signifi cance of the once more rising tide of globalization. It was to the global ‘culture industry’, to an American TV series of 1979, not to 30 years of work by her native intelligentsia, that Germany owed her public awakening to the hideous truth that only then became generally known by the name of the ‘Holocaust’. When the global market fi nally swept away the last vestige of old Germany in 1989-90, the redefi nition of the nation - again the fourth in a lifetime - continued to be hampered by a persisting nostalgia which was only superfi cially directed at the old East (Ostalgie). In reality, it was the last - let us hope, fading - trace of an animosity that runs through 250 years of German literary engagement with the concept of nationhood: the animosity between the official and the bourgeois, between the representatives of state power (which makes people virtuous) and the forces that make money (and so make people happy). In the ‘Weltmarkt’, the confl ict between the economic system and political power has certainly not gone away - if anything, it has intensifi ed - but it is more diffused, at once more intangibly collective and more internal to the individual. For nearly three centuries the German literary and philosophical tradition has been compelled by local circumstances to concentrate on the point where the opposing forces collide. But there has always also been a cosmopolitan, or internationalist, vein in German literature, and those who in recent generations have tapped into it - even perhaps at the cost of a life of wandering or exile - have been more able than strictly national writers to make Germany’s traumas into symbols of general signifi cance for other countries caught like their own between a national past and a global future.

0%

0%

Author: Nicholas Boyle

Author: Nicholas Boyle