Chapter 5: Traumas and memories (1914- )

(i) The nemesis of ‘culture’ (1914-45)

The war that broke out in 1914 began the long collapse of the 19th-century attempt to organize the global economy into separate political empires. For most of the Germans who welcomed the release it brought from over a decade of increasingly ill-tempered rivalry, it was a battle against encirclement by the Triple Entente of Britain, France, and Russia. For Thomas Mann it was a battle of ‘culture’ against ‘civilization’, and of himself against his brother.

All that was truly German - he said in his two volumes of Unpolitical Meditations (Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen, 1918) which he spent the war writing - was ‘culture, soul, freedom, art, and not civilization, society, the right to vote, and literature’.

‘Civilization’ was an Anglo-French superfi ciality, the illusion entertained by left-wing intellectuals generally, and Heinrich Mann in particular, that the life of the mind amounted to the political agitation and social ‘engagement’ of journalists who thought the point of writing was to change the world. Germany, by contrast, knew that ‘Art’ was a deeper affair than literary chatter, and that true freedom was not a matter of parliaments and free presses but of personal, moral, duty. The Western powers, while claiming to fi ght for their ‘freedom’ against German ‘militarism’ were, in this view, uniting to impose their commercial mass

society on Germans devoted to individual self-cultivation.

Mann therefore correctly perceived the association that linked the concepts of ‘Art’, ‘spirit’, ‘Bildung’, and interior Kantian ‘freedom’, with the hostility of the German class of officials, servants of an autocratic state, to such instruments of bourgeois self-assertion as parliamentarianism, free enterprise, and commercialized mass media. When in November 1918 the Emperor and his generals were no longer able to defend, or even to feed, the German population and handed over their responsibilities to the majority socialist party, the bureaucrats remained in offi ce and maintained the attitudes of autocracy into the new era of parliamentary government. In Prussia, the largest state within the republic that agreed its constitution at Weimar in 1919, a socialist administration fi tted seamlessly into the old structure. Oswald Spengler (1880-1936) argued in Prussianism and Socialism (Preußentum und Sozialismus, 1920) for the identity of the two systems, since both aimed to turn all workers into state officials and thereby to answer ‘the decisive question, not only for Germany but for the world […]: is commerce in future to govern the state, or the state to govern commerce?’

Accepting the political revolution which, with remarkably little fuss, had put an end to German monarchy, did not imply abandoning the struggle against ‘civilization’. Indeed, Spengler saw his vast ‘morphological’ survey of world history, The Decline of the West (Der Untergang des Abendlandes, 1918, 1922) as evidence of a pyrrhic victory of the German mind, which through him had been able to make sense of the coming displacement of traditional European culture by technological and mathematical organization.

For Germany the war did not end in 1918. Starvation, infl uenza, civil war, the reoccupation of territory by France to exact reparations, the economic disruption caused by the loss of population and resources and culminating in the infl ation of 1923, all prolonged the conditions of wartime emergency for fi ve years.

By the time the crisis was over, the Weimar Republic consisted of a few magnates whose property interests had survived the infl ation, a working population directly exposed to fl uctuations in the world economy, and the administrators and benefi ciaries of a welfare state 13 times larger than its equivalent in 1914. The intimations of the coming collapse of the European bourgeoisie that unsettled the pre-war world were fi rst fulfi lled in Germany.

The literature of this period of revolutionary transition reflected the instability of institutions and the isolation of individuals.

It was not a time for realism. It was a time for despair, abstract revolt, and utopian hopes of a new beginning. The movement of ‘Expressionism’ was correspondingly most active in the prophetic and emotional forms of poetry and drama. In 1920 the anthology Twilight of Humanity (Menschheitsdämmerung) brought together poems by 23 poets in the service of an indeterminate moral enthusiasm:

Ewig eint uns das Wort:

MENSCH we are for ever united by the word ‘Man’

Expressionist theatre was similarly characterized by a deliberate striving for abstractness and generality through heightened and declamatory language, but by its use of choruses, and stylization of character, it had more success than the poets in representing large-scale industrial and political confl ict: the works of Reinhard Goering (1887-1936), Georg Kaiser (1878-1945), and Ernst Toller (1893-1939) are now undeservedly neglected.

Profound though the social revolution was, it did not change everything. In 1919, commenting on the atmosphere in Berlin, Albert Einstein compared Germany to ‘someone with a badly upset stomach who hasn’t vomited enough yet’. Once the American Dawes Plan of 1924 and a huge associated loan had stabilized the German economy, the Expressionist era was effectively over, a ‘new sobriety’ (Neue Sachlichkeit) reigned in literature, and the continuities could re-establish themselves.

Weimar had seemed an appropriate place for the constituent assembly of the new republic to do its work at least partly because of the late 19th-century myth that in Goethe’s Weimar a cultural nation had been born which prefi gured the political nation. This mythical Weimar could now be regarded as the true and abiding Germany. Nor was the continuity simply ideological. Germany’s multiple theatres survived the deposition of their princely patrons and, subsidized now by government and freed from censorship, continued to provide a forum for drama conceived as ‘art’ rather than simply entertainment. The Protestant clergy and, above all, the universities carried over the role of official intelligentsia that they had occupied under the monarchy into an era that, bewilderingly, lacked a monarch, and the universities almost immediately began an intellectual assault on the new republic.

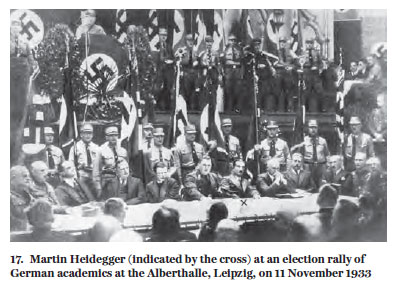

Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), born a Catholic at a time when Catholics were second-class Germans, converted to Lutheranism in 1919 and so gained access to the wider and better-connected world of the Protestant universities. In Being and Time I (Sein und Zeit I, 1927; Part II was never written), Heidegger strangely combined a radically depersonalized re-reading of some of the most fundamental questions in philosophy with a rather Lutheran account of individual moral salvation. His ‘existentialism’ thus provided both the conceptual means for rejecting contemporary society as ‘inauthentic’ and, with his belief that one chooses one’s own history, the excuse for political activism regardless of rationality. Heidegger rapidly became an intellectual totem of the right, but Stefan George’s disciples, now in professorial chairs, also had a deep infl uence on academic discourse in the humanities, directing it away from social and economic concerns to what became known as ‘history of the mind’ (Geistesgeschichte) and elaborating the Master’s cult of the lonely, world-changing historical personality. Friedrich Gundolf (1880-1931) in Heidelberg published an epoch-making study of Goethe in 1916, and Ernst Bertram (1884-1957), professor in Bonn, published a similar study of Nietzsche in 1918, with George’s swastika sign on the title page. The year 1928 saw the publication not only of a major work of literary criticism by Max Kommerell (1902-44), professor in Frankfurt and Marburg, The Poet as Leader in German Classicism (Der Dichter als Führer in der deutschen Klassik), a title which already combined the Wilhelmine vision of Germany with the National Socialist version of monarchy, but also a new and fi nal collection of poems by George himself, The New Empire (Das neue Reich). To express a political opinion was infi nitely beneath George’s dignity, but it was clear from the Hölderlinian diction and military rhythms of the prophetically entitled ‘To a young leader in the fi rst world war’ (‘Einem jungen Führer im ersten Weltkrieg’) that in his view Germany’s humiliation in the recent confl ict was only a prelude to a greater future:

Alles wozu du gediehst rühmliches ringen hindurch Bleibt dir untilgbar bewahrt stärkt dich für künftig getös …

[Everything for which you grew and fl ourished throughout your glorious struggle remains your indelible own, strengthens you for future uproar … ]

Of all state employees, members of the armed forces were least likely to feel loyalty to the new régime which had signed the instruments of surrender and the Versailles Treaty. Ernst Jünger (1895-1998) fought throughout the World War with great distinction and his recollections of four years’ front-line service, Storms of Steel (In Stahlgewittern, 1920), are evidence of the chilling dispassion that was necessary to survive. ‘To live is to kill’, he later wrote, and though the enormous success of Storms of Steel established him as a professional writer, he continued to speak from and to his generation’s experience of mechanized mass warfare. In The Worker (Der Arbeiter, 1931), he interpreted modern economic life as an extension of the total mobilization of wartime: he rightly saw that the extinction of the bourgeoisie and proletarianization of the middle classes, already far advanced in Germany, was destined to become universal, but he wrongly assumed that only a bureaucratic and military command structure could organize the resulting industrial society. Heidegger was impressed by Jünger’s analysis of the modern world, though his reaction was to turn to Hölderlin and Nietzsche as guides to Germany’s future. Gottfried Benn, who had spent the war as a military doctor (and in that capacity had attended the execution of Edith Cavell), was yet more radical in his rejection of the civilian world from whose corruption he lived (he became a specialist in venereal disease). Infl uenced partly by Spengler, and partly by his own experiments with narcotics, he came in the 1920s to despise the superfi cial order modern civilization had constructed over the archaic and mythical layers of human experience: the only true order seemed to him that which he imposed on his poems, sometimes by rather too obvious force. His avowed refusal of a social role for the poet was a deliberate provocation to the socialists and communists who had fi gured alongside him in Twilight of Humanity. Like Heidegger and Jünger, however, he willingly lent an appearance of intellectual respectability to the imperious rhetoric of military leadership favoured by right-wing opponents of the republic.

Not that the left wing was any better. The Communists, bent on their own revolution, and under instructions from Moscow that their fi rst aim must be to destroy the ruling socialist party, were as willing as the right to make use of an anti-bourgeois rhetoric which after the infl ation no longer had a real object but which served to destabilize the fragile political consensus. The savage cartoons of George Grosz (1893-1959) created an image of Weimar Germany as a land of freebooting capitalism run wild, but when Grosz moved to 1930s America, where there was much more free enterprise, and much less social welfare, but where the political impetus provided by the German context was lacking,

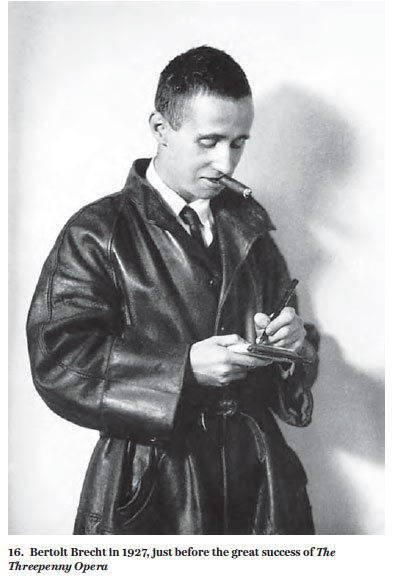

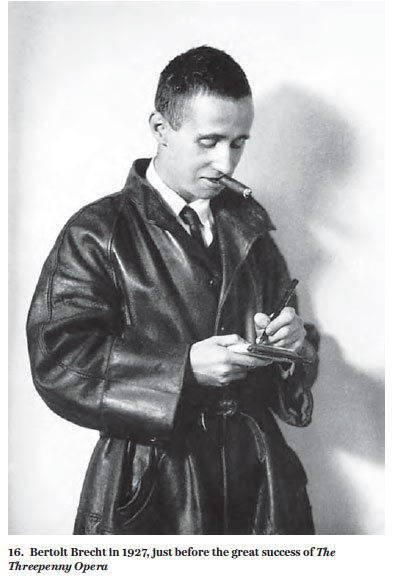

his inspiration deserted him. A sense not just that politics matter, but that political institutions matter too, is lacking throughout the otherwise multifarious and often humane work of the poet and dramatist Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956).

Brecht’s family, paper-makers in Augsburg, belonged to the vanishing bourgeoisie; but after he moved to Berlin in 1924 to become a professional writer-director, his study of Marxism brought him close to those who saw the future in total rule by the state, though he was never a member of the Communist Party. Instead, like Grosz, he drew grotesques, satirical, comic, sometimes even tragic, particularly of an imaginary version of the Anglo-Saxon world - whether 18th-century England, 19th-century America, or Kipling’s Empire - which in the war, and in the boom years that eventually followed, seemed once again to have imposed itself on Germany as the authoritative embodiment of modernity. The jaunty discordancy of Brecht’s works of the 1920s, especially his collaborations with Kurt Weill, The Threepenny Opera (Die Dreigroschenoper, 1928) and Rise and Fall of the Town of Mahagonny (Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, 1928-9), derived from powerfully confl icting feelings towards this vision, or mirage, of ‘capitalist’ life. On the one hand, there was a mischievously amoral appetite for the opportunities of consumption and uninhibited enjoyment that it offered - a theme of Brecht’s since his fi rst play Baal (1918), about a poet who is as ruthlessly self-indulgent as he is totally un-self-pitying. But there was also the moral sense of official Germany, with its long tradition of being offended by irresponsible consumerism, here expressing itself in bitter satire. The driving moral force behind this economic critique, however, was not a political concern for the integrity of the state but a demand, so to speak, for hedonistic justice, for equity in the distribution of pleasure, and solidarity with those to whom pleasure is denied or for whom it is turned into pain. There was a link of substance, as well as of form, with Büchner. One of the weightiest ballads in Brecht’s fi rst collection of poems, Domestic Breviary (Hauspostille, 1927), takes up the

‘Storm and Stress’ theme of the infanticide mother, and the song ‘Pirate Jenny’ in The Threepenny Opera shows us a washer-up who dreams of the ship with eight sails and 50 guns that will put out its fl ags in her honour and then bombard the town where she suffers. But Brecht’s engagement with the society of which he was a part did not extend beyond the desire to shoot it up. For all his claims that the ironical devices which made his productions both scandalous and successful were intended to set his audiences thinking about the political issues that they raised, the only institution of the Weimar Republic that Brecht’s plays really concerned was the theatre. The placards descending from the fl ies, the direct addresses to the spectators, the parodies of grand opera, and the reduction of characters to marionettes in Wedekind’s manner, all encouraged thinking, not about public affairs, but about the theatricality of the performance. It was a complete and successful break with the native German tradition of drama-as-book, but it was also an inverted aestheticism, making Art out of criticizing Art.

The same tendency to perpetuate old concepts under an appearance of criticizing the new can be found in the writings, many of them published posthumously, of Brecht’s Berlin friend and admirer, Walter Benjamin (1892-1940). Benjamin attempted unsuccessfully to become a professor of German literature, and at fi rst devoted himself to relatively unpolitical ‘Geistesgeschichte’.

He later moved closer to Marxism in the quest for a more materialist theory of the relation between art and society, eventually expressed programmatically in the essay ‘The work of art in the age of its technical reproducibility’ (‘Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit’, 1936). Here he argued, rather like Brecht, that in the age of mass-media Art, being no longer able to create individual beautiful objects, had to become political. He thus overlooked the specifi cally German roots of the concept of ‘Art’, the extent to which it was part of the ideology of bureaucratic absolutism, and the consequence that to criticize society in the name of Art was to maintain the values of an oppressive era. Benjamin was for a while associated with the Institute for Social Research (Institut für Sozialforschung)

in Frankfurt, founded in 1923 by the son of a millionaire corn-merchant to investigate the condition of the working classes and later incorporated into the new local university (opened in 1914). When Max Horkheimer (1895-1973) became its director in 1931, it turned to a new project: developing a critical theory of society in general. Among the brilliant talents Horkheimer briefl y concentrated in Frankfurt were the Hegelian and Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse (1898-1979), the psychologist Erich Fromm (1900-80), and a young composer and theorist of music, Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno (1903-69), a pupil of Alban Berg. Adorno, committed to the German musical tradition and impressed by Benjamin’s defence of the role of Art in modern society, was only being consistent when in 1934 he welcomed the Nazis’ ban on broadcasting the degenerate American form of music known as jazz.

The Weimar Republic had few friends among its intelligentsia, but the best and most indefatigable proved, in the end, to be Thomas Mann. During the long German postlude to the war, he rather grudgingly admitted that his elder brother’s politics had proved more realistic than his own, but in 1922 the murder, by right-wing extremists, of Germany’s Jewish foreign minister, the respected and successful Walter Rathenau, shocked him into whole-hearted commitment to the Republican cause. Over the next ten years and with the authority, after 1929, of a Nobel prizewinner, he delivered a number of high-profi le addresses in support of a system he now saw as fulfi lling the promise of the German Enlightenment. At a time when hostility to a Social Democrat government, in which emancipated Jews were understandably prominent, was increasingly taking the form of anti-Semitism, he embarked on an enormous series of linked variations on biblical narratives, Joseph and his Brothers (Joseph und seine Brüder, 1933-43), that deliberately drew attention to the Jewish roots of Western history. The crisis of 1922 also enabled Mann to fi nd a focus for the book he had been writing since 1913, The Magic Mountain (Der Zauberberg), fi nally published in 1924. A sanatorium in Davos provided him in this novel with a metaphor for the rarefi ed atmosphere of high culture in the immediately pre-war years, cosseted, morally lax, and impregnated with a sense of coming dissolution. Hans Castorp, an average ‘unpolitical’ German bourgeois, succumbs, in this unreal environment in which time seems to stand still, to a series of more and less intellectual temptations, from materialist science to hypochondria and sexual dalliance, from psychoanalysis to X-rays and recorded music. A half-comic, but in the end suicidally tragic, dispute on political and moral matters is maintained between Lodovico Settembrini, a representative of liberal and democratic bourgeois Enlightenment, and Leo Naphta, a Jewish Jesuit, whose arguments for amoral theocratic Terror seem - like Nietzsche, whom they echo - a nightmare condensation of the entire German official tradition, Left and Right. In an extreme and climactic moment, Hans Castorp escapes from the sanatorium into the snow but only narrowly avoids death from hypothermia. What draws him back into life is a belief in ‘love and goodness’ which transcends the opposition between Settembrini and Naphta.

He recognizes that his German, Romantic inheritance - from Novalis to Schopenhauer, Wagner, and Nietzsche - gives him a special understanding of the background of death against which life is defi ned, and which, by contrast, gives life its value, but he also recognizes that ‘loyalty to death and to what is past is only wickedness and dark delight and misanthropy if it determines our thinking and the way we allow ourselves to be governed’.

With this insight, more exactly prophetic than any of Stefan George’s oracles, Thomas Mann drew a lesson from the fall of the Second Empire which he could pass on to the Weimar Republic, and which could guide him in his own political engagement, unashamedly German, but unambiguously on the side of ‘life and goodness’. Unfortunately it is an insight that Hans Castorp forgets once he is safe, and he drifts through the fi nal stages of cultural decline into the killing fi elds of the World War. That too was prophetic.

Germany in the 1920s was a mature industrial state, at the forefront of technological innovation (its fi lm industry produced more fi lms than all its European competitors combined), with no empire, a proletarianized bourgeoisie, an active but headless official class, mass communications, and a colossal problem of identity. Its social and political postmodernity made it a natural incubator for cultural tendencies that have since spread widely as other nations have arrived in its condition. With Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt (1888-1985) and Leo Strauss (1899-1973) pioneered political neo-conservatism. Heidegger, one of the fi rst to use the concept of ‘deconstruction’, was the fountainhead of most French philosophy in the second half of the 20th century. The physical appearance of the man-made Western world was profoundly affected by the decision of Walter Gropius (1883-1969) in 1919

to combine education in the fi ne arts and in crafts into a single institution in Weimar, known as the ‘Bauhaus’. The idealist concept of life-transforming ‘Art’, united with functionalist notions of design, was here applied to mass production in industry, buildings, and furniture. In literature too there was a serious quest for ways of adapting old forms to the unprecedented circumstances of a society more deeply revolutionized in defeat than any of the victor powers. The prolifi c novelist Alfred Döblin (1878-1957), a Jewish doctor in the East of Berlin who eventually became a Catholic, wrote his masterpiece in Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929), which uses a highly fragmented manner, reminiscent of Ulysses (though Döblin did not know Joyce’s book when he started), to evoke life in a great industrialized city. Despite its title, it is not a novel of place: Berlin in 1928 is too vast and too modern to have the cosy identity of Dublin in 1904. Berlin Alexanderplatz is a novel of language. The dialect of the main characters, proletarians and petty criminals, informs their semi-articulate conversations and indirectly reported thoughts, carries over

into some of the various narrative voices, and is cross-cut with officialese, newspaper stories, advertisements, age-old folk songs and 1920s musical hits, parodies and quotations of the German classics, statistical reports, and the propaganda of politicians.

Through this modern Babel we make out the story of the released jailbird Franz Biberkopf, big, dim, goodhearted, and shamefully abused by his friends, the breakdown of his attempt to be ‘decent’, and his eventual recovery (perhaps). It is a worm’s-eye view of the Weimar Republic, with its socialists, communists, and anarchists fi ghting obscurely in the background and the National Socialists remorselessly on the rise. Marching songs and rhythms and the memory and prospect of war run as leitmotifs through the book, and the overwhelming symbol of Biberkopf ’s life ‘under the poll-axe’ is provided by a centre-piece description of the main Berlin slaughter-house, fed by converging railway lines from all over the country, a symbol more terrifyingly apposite than Döblin could know.

An intellectual’s view of the destructive possibilities inherent in the directionless multiplicity of modern life was provided in 1927 by the most adventurous book of an author who had previously specialized either in monuments to self-pity or sugary (and not always well-written) stories of post-Nietzschean ‘Bildung’:

individuals who ripen beyond good and evil into mystical or aesthetic fulfi lment. Hermann Hesse (1877-1962) did not deny his origins but he supped German life with a long spoon: born in Württemberg, he travelled in India and settled in Switzerland.

The Wolf from the Steppes (Der Steppenwolf) is a transparently autobiographical account of a personal mental crisis but it is also a psychogram of the contemporary German middle classes.

Harry Haller, the main narrator, personifi es the disorientated ‘Bildungsbürger’ in the post-war era, caught, he recognizes, between two worlds: he loves the orderliness of the bourgeoisie and lives off his investments, he is devoted to the German official culture of classical literature and music, and he also embodies the wolf-like, anti-social, Nietzschean individualism that his class has secretly fostered. However, the new, wide open, Americanized world of the 1920s, with jazz and foxtrots, gramophones and radios, offers him the possibility of dissolving the shadow side of his psyche, the wolf from the steppes, into the myriad alternative personalities latent in him and so of escaping from ‘Bildungsbürgertum’ altogether. In the ‘magic theatre’ of the saxophonist Pablo he enjoys, as if by the aid of hallucinogenic drugs, such experiences as sleeping with all the women he has ever set eyes on, meeting Mozart (who gives him a cigarette), and playing at being a terrorist and a murderer. But evidently this is a highly ambiguous liberation. Haller, who opposed the First World War, knows that in the new age that is remaking him, ‘the next war is being prepared with great zeal day by day by many thousands of people’, and that it will be ‘even more horrible’ than the previous one, and we can see that the ‘magic theatre’ is one of the means by which the horror is being rehearsed. However, since Haller can no more stop war than he can stop death, he turns instead to learning to love, and to laugh at himself. Hesse is honest; he depicts both his own path to equilibrium and its cost: the withdrawal from responsibility for a monstrous, carnivorous mechanism whose workings he has understood with grim clarity.

With the crash of 1929, the time for fantasies of individual fulfi lment was over. As the political tensions within the Republic reached breaking point and unemployment rose to 30%, the cultural compromise that had created the ‘Bildungsbürger’ lost all plausibility. Brecht dropped his fl irtation with consumerism and from 1929 to 1932 wrote a series of ‘didactic plays’ (Lehrstücke), several in cantata form, with minimal character interest, intended to encourage audiences (particularly of school-children) to think of solving problems by subordinating individual concerns, and even lives, to collective programmes.

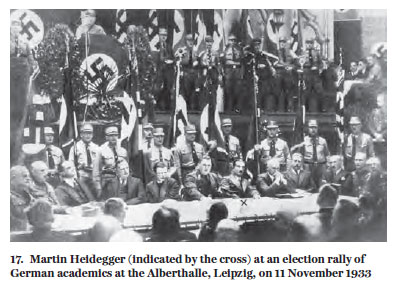

Knowing arrest was imminent, Brecht left Germany on the day after the Reichstag fi re in February 1933 that gave the recently elected Nazi government the excuse to take emergency powers and introduce totalitarian rule. Those who then supported the political nationalism which was Germany’s response to global economic protectionism were the immediate agents of the self-immolation of ‘culture’. Heidegger, now a member of the Party, gave his inaugural address as rector of Freiburg University in May, its title, The Self-Assertion of the German University (Die Selbstbehauptung der deutschen Universität) revealing the cruel delusion of Hitler’s camp-followers. For in the Third Empire there was to be no self-assertion by any institution other than the Party and its Leader, let alone by the university, which for over 300 years had been the heart of the German bureaucracy and for over 200 had given a unique character to Germany’s literary culture. The fi nal degradation of German officialdom to dutiful executants of murderous tyranny was at hand.

Heidegger lent his support to the new government’s rejection of globalization by campaigning for Germany’s withdrawal from the League of Nations, but within a year he had resigned his offi ce and was discarded by the regime, though he remained in the Party.

A similar fate befell Benn, seduced by the idea of ‘surrendering the ego to the totality’. In a radio broadcast in April 1933, he coarsely denounced the obsolete internationalism of ‘liberal intellectuals’, whether Marxists who thought of nothing higher than wage-rates or ‘bourgeois capitalists’ who knew nothing of the world of work, and opposed to it the new totalitarian nation-state which - he claimed, combining Nietzsche and Spengler - had history and biology on its side and showed its strength by controlling the thoughts and publications of its members. So it did, and after a series of violent attacks on him in the Party press for the ‘indecency’ of his poems, he took cover, like Jünger, by rejoining the army - ‘the aristocratic form of emigration’, he said, salving the smart - and in 1938 he was officially forbidden to publish or write. Stefan George bowed out with more dignity before he died in December 1933, refusing (for unclear reasons) to serve in succession to Heinrich Mann as president of the newly purged Prussian Academy. Hauptmann stayed in Silesia, without offi ce, but accepting honours and censorship (The Weavers was not to be performed) until he died after experiencing the bombing of Dresden. Otherwise, virtually all German writers and artists of signifi cance either emigrated or withdrew from sight. German literature could be said to have been officially terminated on 10 May 1933 when the German Student Federation arranged public burnings of ‘un-German works’ throughout the country.

For those emigrants who survived - Benjamin committed suicide rather than fall into the hands of the Gestapo and Toller did the same out of sheer despair - exile in a non-German-speaking country where they were unknown and had little opportunity of publishing usually put the end to a literary career. Alfred Kerr (1867-1948), for example, who made and broke reputations as a theatre critic in Naturalist and Expressionist Berlin, dwindled to a refugee Jewish invalid in his London fl at, though his daughter wrote a touching memoir of their life of banishment in her trilogy beginning with When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit. For Brecht, however, emigration meant liberation. Until 1941 he lived mainly

in Denmark and Finland, but he was already internationally known, he travelled widely, and his plays were put on in Paris, Copenhagen, New York, and Zurich. Since, however, he was writing in professional, though not personal, isolation, and no longer had his own theatre, what he wrote became gradually more reflective, less closely involved with German circumstances, and, without losing its theatricality, emotionally and psychologically more multidimensional. His poetry blossomed. He already resembled Luther and Goethe as a townsman with a love of the vernacular who had taken up with the politics of authoritarianism, and he now came to resemble them in the hide-and-seek his contradictory personality played with the public. (The theories of drama which he now elaborated were part of this game, and need not be taken seriously.) Perhaps because the public had become more diffi cult to defi ne, broader both in space and time than in the Weimar forcing-house, his poetic voice achieved a new level of generality, a German voice, certainly, but addressing everyone caught up in the global confl ict:

Was sind das für Zeiten, wo Ein Gespräch über Bäume fast ein Verbrechen ist Weil es ein Schweigen über so viele Untaten einschließt! […]

Ihr, die ihr auftauchen werdet aus der Flut In der wir untergegangen sind Gedenkt Wenn ihr von unseren Schwächen sprecht Auch der fi nsteren Zeit Der ihr entronnen seid. (‘An die Nachgeborenen’)

[What sort of times are these when a conversation about trees is almost a crime because it includes silence about so many misdeeds […] You who will emerge from the tide in which we have sunk, remember too, when you speak of our weaknesses, the dark time from which you have escaped.]

(‘To later generations’, 1939)

From 1938 Brecht was writing what were effectively morality plays for a world audience, in which the deeper themes of his early work returned: his passionate sense that pleasure and goodness are what human beings are made for and that justice requires that pleasure should be universal and goodness rewarded; his bitter countervailing belief that injustice is general, that it is often necessary for the survival even of the good, and that it may be remediable only by unjust means; and a Marxism which is not a source of answers to these dilemmas, but a background conviction that answers are possible and so should be looked for.

The Good Woman of Szechuan (Der gute Mensch von Sezuan, 1938-9, fi rst performed 1943) was still just about interpretable as a demonstration that in capitalist society moral goodness was necessarily symbiotic with economic exploitation, if the anguished love of the ‘good woman’ herself was overlooked, but The Life of Galileo (Leben des Galilei, 1938-9, fi rst performed 1943) was Brecht’s most personal play, and despite extensively adapting it after 1945, he was unable to fi t it into a Marxist scheme. The pleasure-loving genius with a huge appetite for life who fails the political test and recants when threatened by the Inquisition, but who argues that he serves progress better by devious compliance than by pointless heroism, clearly embodies some of Brecht’s own feelings about the priority he was giving - and had always given - to his literary work over the political struggle. His one genuinely tragic play, Mother Courage and her Children (Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder, 1939, fi rst performed 1941), though written before war had broken out, was the nearest he came in a major drama to commentary on the great events of his age. Set in early 17th-century Germany, in a state of war without beginning

or end, it dramatizes ‘the dark time’ in which Brecht’s generation had, somehow or other, to live. Mother Courage, who has little more than her name in common with Grimmelshausen’s character (and even that has lost most of its sexual connotations), drags her sutler’s wagon after the marauding armies on which she depends for a livelihood. Her calculating, unscrupulous, shopkeeper’s realism - like Galileo’s cunning - makes sense for as long as it serves the purpose of keeping her family alive and together.

But one by one she loses her children to different forms of the goodness she has warned them against. Alone at the end, she has survived - but what for? It was Brecht’s own question to himself.

In 1941 Brecht left Finland for Russia and, without stopping to inspect the workings of socialism, took the trans-Siberian route to the Pacifi c Ocean and California. There he met W. H. Auden (who thought him the most immoral man he had ever known) and found a colony of German émigrés, such as Erich Maria Remarque (1898-1970), author of the gripping pot-boiler All Quiet on the Western Front (Im Westen nichts Neues, 1929), many of them attracted, like him, by the prospect of work in Hollywood. There too Brecht wrote his happiest - and last signifi cant - play, The Caucasian Chalk Circle (Der kaukasische Kreidekreis, 1944-5, fi rst performed 1948, in English). In it the pure, self-sacrifi cing love of another ‘good woman’ and the self-preserving immoralism of an unjust judge, embodied in characters as fully drawn as Mother Courage or Galileo, are united in a moment ‘almost of justice’, while Marxism is relegated to sedately utopian, socialist-realist framework scenes which pretend to underwrite the hope expressed in the principal action. Not all of Brecht’s fellow exiles were as easily reconciled to life in the USA, however. Horkheimer and Adorno managed to re-establish the Institute of Social Research in California and tried there to use the inherited concepts of German philosophy to explain the barbarism engulfi ng Europe. But their joint study, Dialectic of Enlightenment (Dialektik der Aufklärung, 1944), suffers, like the Marxist tradition itself, and like Brecht’s feeble attempts at direct representation of the Nazi regime, from an inadequate theory of politics (treated simply as a cloak for economic interests) and from a limited understanding of the special character of the German society from which they came. It was boorish and inept to equate the capitalism of America, which was paying in blood to save their lives and their work, with genocidal Fascism (as Brecht also did in his lesser plays). Their assault on the American entertainment industry was not just the snobbery of expatriates from the homeland of Art: Adorno and Horkheimer explicitly defended, against the mass market and mass politics that had swept them away, 19th-century Germany’s ‘princes and principalities’, the ‘protectors’ of the institutions - ‘the universities, the theatres, the orchestras and the museums’ - which had maintained the idea of a freedom available through Art and transcending the (supposedly) false freedoms of economic and political life. In thus preparing to hand on to a later generation, as the key to modern existence, the concepts and slogans of the defunct German confl ict between bourgeoisie and bureaucracy, Adorno and Horkheimer committed themselves to much the same half-truths as a writer for whom they had no time at all, Hermann Hesse.

In 1943 Hesse issued from his Swiss retreat his own reaction to the contemporary crisis, The Glass-Bead Game (Das Glasperlenspiel), a novel of personal ‘Bildung’ set in the distant future and in the imaginary European province of Castalia. As the allusion to the Muses’ sacred spring suggests, Castalia is devoted to Art, but an Art which has absorbed all previous forms of artistic and intellectual expression into a single supreme activity, the Glass-Bead Game. A secular monastic order is dedicated to the cultivation of the Game, and the novel tells of the development of its greatest master, Josef Knecht, to the point where he recognizes the need to relate this religion of Art to the world beyond it.

Castalia is threatened by war, economic pressures, and political hostility, as in the ‘warlike age’ of the mid-20th century, in which the Game originated. Knecht’s end, however, and that of the novel, is obscure: has he indeed secured the survival of the Castalia that preserves his memory? Or has he, as his Castalian successors would clearly like to believe, betrayed Art to Life and been punished accordingly? The Castalian world of the Spirit (Geist) seems hermetically detached from the historical world of society, and even if Spirit is in reality dependent on Society, it seems not to acknowledge, or even to know, that it is. Hesse’s anxiety about the ability of Art and the Spirit to survive into the post-war era is expressed with more modesty, and greater political astuteness, than we fi nd in Dialectic of Enlightenment, but he is no more able than Adorno and Horkheimer to represent those concepts as peculiar to a particular time and place and tradition.

That was to be the task of another German resident of California, Thomas Mann, who had arrived in America in 1939, and from 1943, following daily the news of Germany’s military collapse, worked intensively on his greatest novel, completed and published in 1947, Doctor Faustus. The life of the German composer Adrian Leverkühn, narrated by a friend (Doktor Faustus. Das Leben des deutschen Tonsetzers Adrian Leverkühn erzählt von einem Freunde). Mann consulted Adorno about his manuscript, particularly its musical sections, and sent Hesse a copy of the published work with the inscription, ‘the glass-bead game with black beads’, but his book went to the heart of the issue that their books evaded. Doctor Faustus is a reckoning with the German past at many levels. It gives a fi ctionalized account of the social and intellectual world of the Second Empire and the Weimar Republic, particularly Munich (complete with proto-fascist poets).

In taking the life of Nietzsche as its model for the life-story of Adrian Leverkühn, and his apparent purchase of world-changing artistic achievement at the cost of syphilitic dementia, it asserts the typicality of a fi gure whose thinking was all-pervasive in 20th-century Germany and who contributed in his own way to what passed for Nazi ideology. It is shot through with allusions to earlier phases of destructive irrationalism in German literature and history, and above all it appropriates the central myth of modern German literature to suggest that the story of Leverkühn parallels the story of modern Germany, for both are the story of a Faustian pact with the devil. Links with contemporary reality punctuate the narrative, which is in the hands of Leverkühn’s friend, Serenus Zeitblom, a retired schoolteacher, who starts his work, like Mann, in 1943 and ends in the chaos of total defeat in 1945. The ultimate refi nement in this supremely complex work, however, is that, for all the apparent concentration on the artist fi gure Leverkühn and his assimilation to the fi gure of Faust, the true representative of Germany in it is Zeitblom. Zeitblom is a state official, steeped in the classics and German literature, who shares Thomas Mann’s ‘unpolitical’ attitude to the First World War, but not his post-war conversion; he does not emigrate, he has two Nazi sons, and he dissents from Hitler’s policies only quietly, on aesthetic grounds, and as they start to fail. Germany’s fate is here represented not by Faust, Art, and the life lived in extremis, but by the man who believes in these ideas, who needs them to give colour and signifi cance to his life, and who structures his narrative in accordance with them. The moral climax of the book, the point when it represents directly the sadistic monstrosity of the Third Reich, is Zeitblom’s chapter-long account of the agonizing death from meningitis of Leverkühn’s fi ve-year-old nephew, supposedly fetched by the devil. For a dozen pages this narrator tortures a child to death to justify his own desire to live out a myth. His fellows did as much across German-occupied Europe. In Zeitblom (the name means ‘fl ower of the age’), Thomas Mann created an image of the German class that saw itself as defi ned by ‘culture’ and that accepted Hitler as its monarch, its metaphysical destiny, and its nemesis.

(ii) Learning to mourn (1945- )

In 1967 the psychologists Alexander and Margarete Mitscherlich (1908-82 and 1917- ) published The Inability to Mourn (Die Unfähigkeit zu trauern), an analysis of Germany’s collective reaction to the trauma of 1945, the ‘zero hour’ in German history when the past was lost, the present was a ruin, and the future was a blank. Their conclusion was that there had been no reaction:

Germany had frozen emotionally, had deliberately forgotten both its huge affective investment in the Third Reich and the terrible human price paid by itself and others to rid it of that delusion, had shrugged off its old identity and identifi ed instead with the victors (whether America in the West or Russia in the East), and had thrown itself into the mindless labour of reconstruction, which created the Western ‘economic miracle’ and made East Germany the most successful economy in the Soviet bloc. This analysis, and in particular its conclusion that Nazi thinking was still as omnipresent in (West) German society as the old Nazis themselves, had a powerful infl uence on the revolutionary generation of 1968 and reinforced the accepted wisdom that ‘coming to terms with the past’ (Vergangenheitsbewältigung) was the major task of contemporary literature. But there was a good deal more to mourn than unacknowledged Nazism, repressed memories of Nazi crimes, the horrors of civilian bombardment, the misery of military defeat, or the uncomfortable fact that in the four years before the foundation of the two post-war German states in 1949 the prevailing mood was not joy and relief but sullen resentment both of the Allies and of the German emigrants.

There was the further complication that the past calling out to be reassessed did not begin in 1933, it was potentially as old as Germany itself, while the present, for all the talk of reconstruction, had no historical precedents. It might resemble the aftermath of the Thirty Years War, though without the princes, but more importantly it was without a bourgeoisie: both German states were workers’ states - one was just wealthier than the other. But because in the Eastern German state the absolutist rule of officials survived under the name of ‘socialism’, it created an image of its Western rival on the model of officialdom’s old enemy and characterized the Federal Republic as ‘bourgeois’

Germany. With the building of the Wall in 1961, this double illusion was set in concrete and barbed wire and exercised an increasingly malign infl uence on German intellectual life on both sides of the barrier. For the greatest obstacle to clear-sighted assessment of the present and the past was a factor which the Mitscherlichs did not mention: that neither of the world powers which had divided Germany between them wished to encourage it. Rather, they wanted their front-line German states, between which the Iron Curtain ran, to understand themselves as showcases for their respective blocs in the bipolar global system.

‘Denazifi cation’ procedures were stopped in the West, and held to be unnecessary in the East. Only after 1990 were German writers released from this imposed and misleading confrontation, and as they became free to understand Germany’s position in a global market and a global culture in which national identities had long been dissolving, they also became free to address their own history.

After 1945, many emigrants stayed where they were or avoided settling in Germany. By this time they were anyway largely exhausted. Thomas Mann, who returned to Switzerland, and Hesse, who continued to live there, were honoured - Hesse with the Nobel Prize in 1946 - but unproductive. The Communists returned to the Russian zone, but apart from Brecht they had little international standing. Adorno came back in 1949 to a professorship in Frankfurt, where the Institute for Social Research was reopened in 1951. In the West the task of reacting in literature to the traumatic past was in the hands of a new generation of ex-servicemen and ex-prisoners of war, many of whom arranged to meet annually to discuss their work and became known as ‘Group 47’ (Gruppe 47). For this new generation, the problem of inheritance was particularly evident in poetry. Adorno’s famous dictum of 1949 that ‘to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’ reflected partly the special role of lyrical poetry in Germany as the literary medium for the exploration of individual ethical experience. That this role was over was emphatically stated in the last phase of the work of Gottfried Benn, which became known to the public in the early 1950s. Despite the Nazi prohibition, he had continued to write in secret, especially what he called ‘static poems’, regular in form and rich in imagery of autumn and extinction. A collection privately circulated in 1943 contained one of his greatest poems, ‘Farewell’ (‘Abschied’), a tormented admission that in 1933 he had betrayed ‘my word, my light from heaven’, and that it was impossible to come to terms with such a past: ‘Wem das geschah, der muß sich wohl vergessen’ (‘Anyone to whom that happened will have to forget himself ’). After this personal outcry, his public stance of unyielding nihilism, in the post-war years, was entirely consistent:

es gibt nur zwei Dinge: die Leere und das gezeichnete Ich [there are only two things: emptiness and the constructed self ]

(‘Nur zwei Dinge’, 1953)

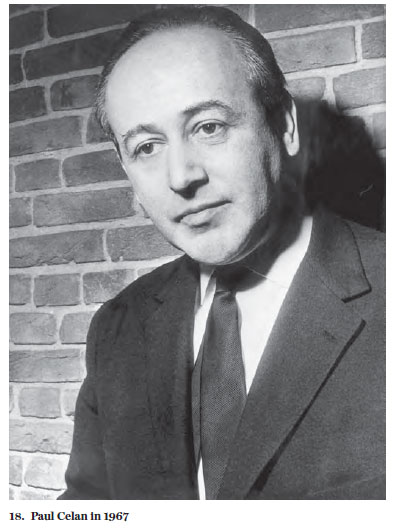

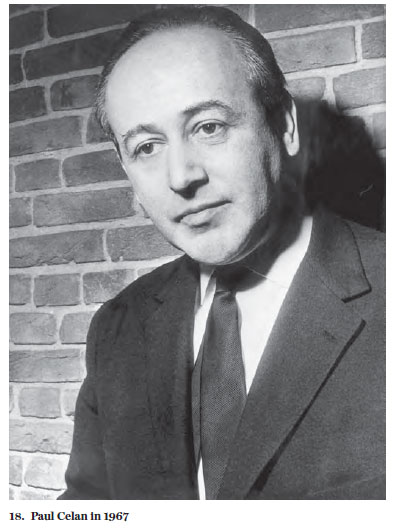

If the self has become pure construction, not made out of interactions with its past experiences or with a given world, there is no place for poetry as it had been practised in Germany from Goethe to Lasker-Schüler. The poet who showed Adorno that it was still possible to write poetry in the knowledge of Auschwitz had certainly understood this lesson. There is no role for a self, or for any controlling construction, in the work of Paul Celan (1920-70), a German Jew from Romania, both of whose parents were killed in a death-camp, and who chose to live in Paris, where he committed suicide.

Celan is best known for the fi nest single lament for the Jewish genocide, ‘Death Fugue’ (‘Todesfuge’), an erratic block in the otherwise over-lush collection Poppies and Memory (Mohn und Gedächtnis, 1952), but he seems to have felt that even this impersonal, repetitive musical structure, with its motifs of ‘black milk’, ‘ashen hair’, the name of Jewish beauty, ‘Sulamit’, and the terrifying climactic phrase ‘death is a master from Germany’ (‘der Tod ist ein Meister aus Deutschland’), imposed too much of a subjective order on a strictly unthinkable event.

In his later collections (e.g. Speechgrid [Sprachgitter], 1959; Breathturn [Atemwende], 1967), he thought of the poem as a ‘meridian’, an imaginary line both linking disparate words and names and events and, by its arbitrariness, holding them apart, so re-enacting the meaninglessly violent juxtapositions and discontinuities of 20th-century history. Although many of the elements, including the vocabulary, are hermetically personal, the call for interpretation that these Webern-like miniatures embody makes them strangely public statements in which the anguish of the bereaved survivor is largely uncontaminated by Germany’s growing ideological division.

[…] Stimmen im Innern der Arche:

Es sind nur die Münder geborgen. Ihr Sinkenden, hört auch uns. […]

[Voices inside the Ark: Only our mouths are rescued. You who are sinking, hear us too]

At the same time as Benn was marking the end of poetry as the coherent utterance of a solitary private voice, Brecht was providing it with a new role as the public voice of personal political engagement. He proved by far the strongest infl uence on the poetry of both the Federal and the Democratic Republics, but the infl uence was as ambiguous as the engagement. Brecht had returned to Europe in 1947 and, prevented by the Americans from entering the Western zone, settled instead in the East, where he was given a theatre and a privileged position as the jewel in the new republic’s cultural crown. While he did not publicly oppose the military suppression of the workers’ revolt in 1953, he wrote a series of epigrammatic poems sardonically distancing himself from the action (perhaps the government should elect itself a new people?) and asserting, presumably as a justifi cation of his position as court poet, the social value of literary pleasure. The example both of this last, laconic manner and of his earlier more discursive poetry enabled later poets to address public issues with directness and, often, lightness of touch. But his accommodation with the Communist régime and his failure to unmask either its false claim to cultural continuity with the German ‘classical heritage’ or the reality of its institutional continuity with the bureaucracy of the Third and Second Empires set a bad precedent. Even the most gifted West German poet of the next generation, Hans Magnus Enzensberger (born 1929), succumbed to the assumption that the complacencies and contradictions of life in the Federal Republic lit up by his satirical fi reworks were somehow a consequence of the division of the world between Right and Left. It seemed to him (as it did to all of us) that to be modern was to be subject to the threat of thermonuclear Mutual Assured Destruction by these two opposing systems. When, therefore, he wrote a counter-poem to Brecht’s ‘To later generations’, he began it with an equation of the Cold War and the Second War which became obsolete in 1989:

wer soll da noch auftauchen aus der fl ut, wenn wir darin untergehen?

[who else is supposed to emerge from the tide if we sink in it?]

(‘Extension’ [‘Weiterung’])

By contrast, Celan’s revision of Brecht’s poem gets much closer to the heart of Germany’s diffi culty with its past-haunted present.

Poetry, Celan knew, needed a purifi cation of language and memory, not the prescription of acceptable topics:

[…] Was sind das für Zeiten, wo ein Gespräch

beinah ein Verbrechen ist, weil es soviel Gesagtes mit einschließt?

[What sort of times are these when any conversation is almost a crime because it includes so much that has been said?]

(‘A Leaf ’ [‘Ein Blatt’], 1971)

In drama, Brecht, of course, was everywhere. He wrote nothing of importance after his return to Germany, but in his decade with the Berliner Ensemble he created a model of modernist, politically didactic theatre which, while at fi rst having little effect on the resolutely Second Empire traditions of production in the East, gained great authority in the West, especially after 1968, and made it possible to conceal a lack of direct engagement with the literary heritage beneath an appearance of critical detachment.

The institutional continuity, however, was virtually unbroken: ass in 1918, Germany’s theatres survived the revolution and not for 20 years did major new writing talent emerge. Even then the function assigned to the theatre by a new generation of producers and writers was what it had always been, except in the brief bourgeois period before 1914 - to be a state institution in which the intellectual elite could through Art perfect the morals of the citizens (or subjects). The plays of Rolf Hochhuth (born 1931) do not deny their Schillerian ancestry. His denunciation of Pope Pius XII for complicity in the murder of Europe’s Jews (The Representative [Der Stellvertreter], 1963) was written in fi ve acts and a form of blank verse, and concentrated on issues of personal moral responsibility. Hochhuth’s determination to fi nd highly placed individuals to blame for great crimes - Churchill in Soldiers (Soldaten, 1967); Hans Filbinger, the prime minister of Baden-Württemberg, in Lawyers (Juristen, 1979) - was on occasion highly effective (Filbinger was forced to resign). But it did not help a broader understanding of the historical and cultural context that made the crimes possible. Moral improvement might not seem to be the purpose of the explosively entertaining and hugely successful fi rst play of Peter Weiss (1916-82), a Jewish emigrant and Communist who had lived in Sweden since 1939.

The Persecution and Murder of Jean Paul Marat Represented by the Theatre Company of the Hospital of Charenton under the Direction of M. de Sade, usually known as Marat/Sade (1964), plays to the gallery with sex, violence, and madness, slithering between illusion and reality, with songs and self-conscious effects in the manner of the early Brecht, and with an early Brechtian theme: the confl ict between the isolated hedonist, Sade, and Marat, the spokesman of impersonal and collective revolutionary action. But Weiss himself saw it as a Marxist play, and in his next, much grimmer, work, The Investigation (Die Ermittlung, 1965), a documentary drama drawing on the transcripts of the recent trial in Frankfurt of some of the staff in Auschwitz, he selected his material in accordance with the thesis of Brecht’s Third Reich plays: that Hitler could be explained by the logic of big business.

Weiss’s ideas were formed in the 1930s and contributed minimally to German self-understanding. The three volumes of his last work, the novel Aesthetics of Resistance (Ästhetik des Widerstands, 1975-81), reiterated the fallacy that had done so much damage in the inter-war years: that ‘Bildung’ was a supra-historical value with no particular basis in the German class structure. In the GDR, by contrast, Heiner Müller (1929-95), as director of the Berliner Ensemble, combined his own passionate demand for humanistic socialism, which he felt states always betray, with Brechtian devices taken to a postmodernist extreme, to create extraordinarily powerful works which frequently proved too much for the GDR authorities and had little in common with the armchair leftism prevalent in the Federal Republic. In a loose cycle which opened with Germania Death in Berlin (Germania Tod in Berlin, 1977) and closed with its intertextual counterpart Germania 3 Ghosts at The Dead Man (Germania 3 Gespenster am Toten Mann, 1996), a lament for the GDR, Müller puts bodies, language, and history through the mincing machine; cannibalism, mutilation, and sexual perversion abound; theatrical conventions are strained to the limit and beyond; and the contributions of Prussian militarism, Nazism, and Stalinism to the formation of the modern German states are brutally demonstrated. These plays have the uninhibited wildness of true mourning. However, since their underlying assumption is that the real victim of the German past has been socialism, they are mourners at the wrong funeral.

As for narrative prose, the sharpest insights tend to be found at the beginning of the period of German division, before the confrontation of the two republics had been consolidated. Much of the best writing of Heinrich Böll (1917-85) is in the disillusioned and understated short stories he wrote in the immediate post-war years: stories of military chaos and defeat, of shattered cities and lives, of the black market, hunger, and cigarettes. Traveller, if you come to Spa … (Wanderer, kommst du nach Spa … , 1950)

is the interior monologue of a fatally wounded ex-sixth-former carried to an emergency operating theatre in the school he left only months before. He recognizes the room from a fragment of Simonides’ epigram on Thermopylae which he had himself written on the blackboard, and most of the brief narrative is taken up with enumeration of the cultural objects that still litter the corridors - the bust of Caesar, the portraits of Frederick the Great and Nietzsche, the illustrations of Nordic racial types.

The bloodstained downfall of ‘Bildung’ has been given us in cruel miniature. Böll’s most ambitious investigation of the Nazi infection in the German body politic was the novel Billiards at 9.30 (Billard um halbzehn, 1959), which spans the period from the end of the 19th century to 1958. Three generations of an architect family have been involved with a Benedictine monastery: the grandfather built it; the father blew it up in the Second World War, nominally for military reasons, but in fact because he knew it to be corrupted by Nazism; the son is rebuilding it, unaware who was responsible for its destruction.

Round this theme is woven a picture of a society in which former criminals, their victims, and their opponents mingle on equal or unequal, but usually unjust, terms. During the Adenauer years, Böll, also a Catholic Rhinelander, seems to have seen himself as the moral conscience of a Church compromised by its wartime record and by its association with wealth and power in the new and predominantly Catholic Germany. But in his later work the sense of a historically defi ned Germany measured by an external standard of justice faded, the targets of his critiques became more secular, and his position became more simply that of socialist opposition to the Christian Democrat Party (e.g. The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum [Die verlorene Ehre der Katharina Blum], 1974). Böll remained interested in modernist techniques such as multiple, undefi ned, or unreliable narrative viewpoints, but the clunking symbolism and schematic morality already apparent in Billiards at 9.30 became more pronounced and his original fi erce identifi cation with a unique moment in the national life was lost.

Günter Grass (born 1927) followed a course rather like Böll’s, though Böll got his Nobel Prize in 1972, while Grass, more of an enfant terrible, had to wait until 1999. Grass is a poet, dramatist, graphic artist, and prolifi c novelist, but he will be remembered above all for one book. The Tin Drum (Die Blechtrommel, 1959) is the life story of Oskar Matzerath, who begins, like Grass, on the interface between the German and Polish communities in Danzig, who decides at the age of three to stop growing, who drifts, lecherous and seemingly invulnerable, though armed only with his tin drum and a voice that can break glass when he sings, through the absurdist horrors of the Third Reich, and who is fi nally incarcerated in a lunatic asylum in the Federal Republic where he composes his memoirs. The novel stands out from everything else written, by Grass or others, about the Nazi period for the amoral exuberance of its narration. Oskar is, at most, passingly puzzled by the eagerness of these adults to destroy each other and the nice things he enjoys. The amorality is

essential, for it reflects that of the acts and actors that are being described. So too is the exuberance, for against all the evil and death, from which the book refuses to avert its gaze, it asserts the value of life and pleasure - the untiring verbal inventiveness, some of it encouraged by Döblin’s example, is a sustained act of resistance. But the crucial device that makes The Tin Drum into an exceptionally powerful analysis of how the German catastrophe happened is its parodistic relation to the German literary tradition - specifi cally to the tradition since the last comparable catastrophe, the Thirty Years War. Grass goes back to the early sections of Grimmelshausen’s Simplicissimus to fi nd a narrative standpoint from which he can encompass a political development that ends in Nazism and a literary development that ends in Oskar Matzerath. Oskar learns to read from Goethe’s novel of personal maturing, Wilhelm Meister, regarded since the Second Empire as the fountainhead of ‘Bildung’, and from a life of Rasputin. That Goethe and Rasputin could also, grotesquely, go hand in hand in German 20th-century history is shown by a novel in which every convention of ‘Bildung’ is overturned, starting with the idea of personal growth, and the course of events seems to be determined not by Nature or Spirit but by a homicidal maniac. In Grass’s later works - even the next two books in what the English scholar John Reddick has called his ‘Danzig trilogy’ - the inventiveness became arch or stilted and the themes lost urgency as they became politically correct (e.g. The Flounder [Der Butt], 1977). The Wall made not only the GDR but the Federal Republic too a more introverted place and, responding to the need to defend public life from the left-wing Fascism of the Baader-Meinhof gang, and perhaps inspired by the example of Thomas Mann, Grass became a reliable and important campaigner for the Social Democrat Party as he became a less penetrating analyst of his world.

Because much of the writing of Arno Schmidt (1914-79) was done in the 1950s, and from 1958 he led the life of a (married and atheist) hermit in rural lower Saxony, he was insulated from these local diffi culties and maintained, partly thanks to his enormous erudition, a broader view of German nationhood. The Heart of Stone (Das steinerne Herz, 1956) balanced an unfl attering picture of both the modern zones with a sub-plot dependent on the earlier trauma from which the contemporary division of Germany derived: the absorption of the independent principalities, in this case the Kingdom of Hanover, into Bismarck’s Empire. In The Republic of Scholars (Die Gelehrtenrepublik, 1957), Schmidt wrote a science-fi ction parable of the Cold War, that other and larger-scale determinant of German identities, set in a post-World War Three era, when German is a dead language. Schmidt’s eccentricities of style, spelling, and punctuation were part of his deliberate detachment from his contemporaries and should not be dismissed simply as pastiche of Joyce - though his magnum opus, Bottom’s Dream (Zettel’s Traum, 1970), 1,300 multi-columned A3 pages weighing over a stone, owed much to Finnegan’s Wake.

Uwe Johnson (1934-84) chose a different way to preserve his independence and his ability to write, moving from East to West Germany in 1959, spending much of the 1960s abroad, and settling in England in 1974. He developed a narrative method without a privileged narrator of any kind, piecing together fragments of discourse in a montage which eventually made extensive use of newspaper material: there is no single truth about the lives of his characters or about their relation to the major public events which intimately affect them. Speculations about Jakob (Mutmaßungen über Jakob, 1959) treats the murky circumstances surrounding the death of a man who is a ‘stranger in the West, but no longer at home in the East’ at the time of the Hungarian uprising and the Suez crisis, while The Third Book about Achim (Das dritte Buch über Achim, 1961) asks whether a personality is continuous across the divide between the Nazi years and the GDR and fi nds no answer. The possibility of socialism with a human face, already an issue in Speculations about Jakob, is a central theme in the four volumes of Anniversaries (Jahrestage, 1971-83), which take up some of the same characters and follow every day of their lives throughout the year 1967-8, cross-cutting the German past, the American present, and the crushing of the Prague Spring. In comparison with these powerful books, the experiments in narrative indeterminacy of Christa Wolf (born 1929), who stayed in the GDR, joining the party hierarchy and literary bureaucracy, seem relatively colourless.

The Quest for Christa T. (Nachdenken über Christa T, 1968) shows little awareness of the social constituents of personality, despite spanning the same period as The Third Book about Achim.

Her autobiographical Patterns of Childhood (Kindheitsmuster, 1976), however, impressively presents both the illusions of a Nazi childhood and the traumatic effect of the transition to the later standpoint from which she tries to write.

Since 1945 the challenge facing Germans writing about Germans has been to transform trauma into memory and to understand the present by mourning the past, to show what it is to be German by telling stories broad and deep enough to contain the indescribable. After 1961 that challenge became even more diffi cult, and only those whose narrative could rise to include the global power relationships which were imposing on Germany an economic, social, and cultural schizophrenia had any chance of success. Only a resolutely international or historical perspective could resist the hypnotic attraction of the great lie on which German division was based: that the Democratic Republic was a nation freely working to realize socialism, when it was actually, as the Wall proclaimed, an old-fashioned bureaucratic dictatorship maintained by the military force of a foreign power. Such a perspective was easier to attain in philosophy than in literature.

Heidegger and Jünger in their later, and unrepentant, work perhaps achieved it, if for quite the wrong reasons. Adorno paid a cruel penalty for his continued adherence to ‘Bildung’ when he was pilloried by students as a reactionary and, probably as a result, died of a heart attack in 1969; but the tradition of the ‘Frankfurt School’ was carried on and decisively broadened by his pupil Jürgen Habermas (born 1929). Habermas sought a synthesis of German philosophy with the American and British traditions (rejected by Adorno) in a theory of evolving democratic argument: in democracies Enlightenment was embodied in institutions (The Theory of Communicative Action [Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns], 1981). He thereby both related the constitutional order of the Federal Republic to that of other Western nations and marked it off critically from the German past. His fear that, none the less, the government of Helmut Kohl was encouraging a nationalist form of West German patriotism which would efface the difference between the Federal Republic and earlier German states was expressed in 1986-7 in his criticisms of revisionist historians of the Jewish genocide (the ‘battle of the historians’, or ‘Historikerstreit’). Arguably, however, Kohl was consciously concerned only that Germany should also mourn its 11 million casualties of the Second World War: a true assessment of the Third Reich was possible only if its full cost was recognized.

That goal came signifi cantly nearer in 1989 with Russia’s withdrawal of military cover from Eastern Europe and the collapse of its puppet regimes. In East Germany the last survival from the era of bureaucratic absolutism came to an inglorious end, and with it 30 years of false consciousness for the whole nation. Those, like Christa Wolf, who had already once rebuilt their lives on those hollow foundations could not be expected to reconstruct themselves after a second trauma. But for established Western writers and younger writers from the East a new degree of honesty became possible. After an angry critique of Kohl’s handling of reunifi cation that was more a political intervention than a novel (Too far afi eld [Ein weites Feld], 1996), Grass returned to something like his old form with Crabwalk (Im Krebsgang, 2002), centred on the fl ight of East Prussians from the advancing Russian armies in 1945 and the torpedoing of a refugee ship with the loss of 9,000 lives. His admission of service in the Waffen-SS in his autobiography of 2006 also showed that his portrait of Oskar Matzerath was closer to reality than anyone had been prepared to allow when The Tin Drum was fi rst published. In 2005 the prizewinning poet Durs Grünbein (born 1962) attempted to address the most notorious of all Allied war crimes, the fi re-bombing of Dresden, from the point of view of a native of the city, taking into account Dresden’s political and cultural history, its associations with the Nazis and its dismal reconstruction in the GDR: incongruities of tone were essential to the poem but brought it a mixed reception (Porcelain. Poem on the death of my city [Porzellan. Poem vom Untergang meiner Stadt]). Germany’s inability to mourn the terrible bombing campaign against its cities had been the subject of a controversial study by W. G. (‘Max’) Sebald (1944-2001), On the Natural History of Destruction (literally: Literature and the War in the Air [Luftkrieg und Literatur], 1999), itself a sign that the taboo was being broken. Sebald’s novels, the most striking event in German literature of the 1990s, are both single-minded and endlessly varied in their concentration on the process of remembering past violence, the process by which, as we are told in The Emigrants (Die Ausgewanderten, 1992), a dead body, snowed up on the mountainside, will eventually, after many years, emerge at the foot of a glacier. Like Uwe Johnson, Sebald, long a professor at the University of East Anglia, had to settle outside Germany in order to give his memory the freedom and scope necessary for his literary project. The lives and deaths that his stories retrieve from the ice ramify round the world. Though the German catastrophe is usually their overt or covert point of reference, they involve highly detailed presentations of many seemingly unrelated topics and locales: Istanbul and North America, the architecture of railway stations, the history of the silk industry, and the works of Sir Thomas Browne. Germany appears to be quite tangential to The Rings of Saturn. An English Pilgrimage (Die Ringe des Saturn. Eine englische Wallfahrt, 1995), which is concerned (as the title indicates) with the patterns made by the debris left over from another world-historical implosion, that of the British Empire. By his deliberate ambiguity of genre - are we reading fi ction, autobiography, history, or documentary?; are the blurred photographs scattered through the narrative authentic or staged, relevant or irrelevant? - Sebald replicates both the layers of forgetting that have to be excavated to get at the past and the variety, always eluding unity, in what we are trying to recover.

The books have a unity, however, and it lies in something wholly German: their cultivation of exquisitely calm, statuesque, and elaborate sentences which, apart from little, scarcely noticeable, 20th-century spoilers, could have been written by Goethe. It is these which tell us that this view of our present condition, global though it is in its reach, is achieved from a historically and culturally particular standpoint - a tragic standpoint because it is German and because in no other language would it have been necessary or possible to write Sebald’s greatest single sentence, a ten-page account of the concentration camp in Theresienstadt, in

his last novel, Austerlitz (2001). Sebald’s work is a clear sign that since the turning point (Wende) of 1989-90, German literature has resumed its original post-war search for a national historical identity, a search that is important to all of us, not just because every nation has similarly to fi nd its place in an ever more integrated world system, but because the German example makes it peculiarly clear that what matters in the end is not identity, national or personal, but the pursuit of justice.

0%

0%

Author: Nicholas Boyle

Author: Nicholas Boyle