Lesson 11: Resurrection Part 1

One day we will leave this home. That which we have to think about is what will happen after death. This is important otherwise we will not have determined anything about the sunset for death is a reality which reaches everyone, whether or not they so desire.

Is death the end of life? Is death non-being, destruction, annihilation and the end or is death a change and a connection from one world to another? Do you recall that in our discussion of world view we said: One of the three questions which naturally arises from an individual is: Is the life of every individual human being limited to these few years of life in this world and is death the end of human life or is it that real human life which is eternal and forever begins at the time of death and this short life in this world is an introductory phase for structuring one's eternal fate with one's deeds?

"What is the life of this world but amusement and play? But verify the home in the hereafter, that is life indeed, if they but knew."(29:64)

In reality that which is destroyed and torn asunder at death is the material form of a human being but the truth of a human being which is one's very spirit and non-material dimension. This is never destroyed. Rather, according to the Holy Quran,

"And they say, 'What! When we lie hidden and lost in the earth shall we indeed be in a creation renewed?' Nay, they deny the meeting with their Lord. Say, ‘The Angel of Death, put In charge of you, will take the souls then you shall be brought back to your Lord.' " (32:10-11)

In order to attain the most correct and real answer to this question, we will study three issues which are the principle bases of it: First, the human being eternal; second, the possibility for the resurrection; and, third, proof of the resurrection.

The Human Being Is Eternal

As proving the existence of a world after death without the concept of the subsistence and eternality of the human being makes no sense, in this section, the two-dimensionality of the human being will be discussed. We ask the question: Is there anything other than the material frame within the existence of the human being which we call spirit which is capable of subsisting or is the human being solely determined by this very material dimension?

The Human Being is a Two Dimensional Being

The two-dimensionality of the human being is accepted by all of the various contemporary schools of thought. There is no doubt among them that in addition to the material dimension of the human being, it also has another dimension which separates it from other creatures. That which the various opinions held differ upon is whether or not the spiritual dimension of the human being follows its material dimension or not. Does it originate from there or is it independent? In other words, does its authenticity belong solely to the material dimension or does the spiritual dimension also have authenticity?

The material schools of thought generally believe that the spirit and spiritual dimension of the human being stems from the material. They believe it to be the reflection of the material dimension. Opposed to this, other schools of thought believe that the spirit has authenticity and independence.

The Spirit in Material Schools

Material schools of thought accept that the world is the monopoly of the material and in general they deny the existence of the metaphysical. They justify the existence of non-material phenomena by showing them to be the effects of the material. As to the spirit (and spiritual phenomena), these schools of thought busy themselves with justifications and vain fantasies. Materialists say: The true spirit is not separate from the material and physical dimension of the human being. They claim that the incorrect knowledge of former scholars who said, "The spirit is independent and after death will be reborn," is clear.

Dr. Arani says about this, "In the past ages the belief was held that the spirit is independent. Descartes assumed the spirit to be a fluid. Gnostics believed that the spirit is in love with the body. The new science has drawn a red line around these fantasies which prove that the spirit does not exist as an independent entity but rather stems from the material."

Materialists accept the fact that the spirit and spiritual phenomena are material and are among the particularities of the material because they believe that everything which exists is either material or has the particularities of materiality and that no particularities can be found which do not relate to the material.

Dr. Arani says, "From that which has been said, the following must be accepted as the definition of the spirit and life: 'The spirit and life consist of particularities determined by a special material facility. What we mean by special facility is those very cells or nerve cells. Thus the spirit has no external existence. Rather they are particular to a living form."

In describing the above, he says, “If material organs find the special time-place relationship to each other, they will possess the spirit and the spirit consists of these very relationships of the material organs which have a spirit.

Originality and Independence

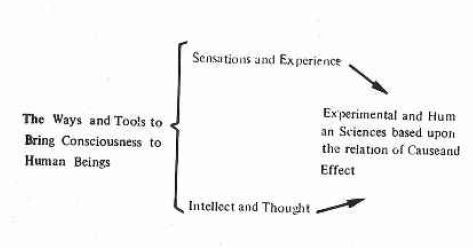

In the previous discussions, this point has been intimated that experimental sciences are not able to prove or disprove the existence of non-material creatures like the spirit. Now let us see if there are other ways to prove the independence of the spirit and to be able to recognize it or not?

The best method of bringing consciousness to humanity from among the phenomena of the world is to move from cause to effect. Each one of us in our daily lives have been able to make correct judgments about the existence of a phenomenon or about its particularities and how it works without having had any direct contact with it. That is, we have only seen its effects and based upon that we have expressed an opinion. In the area of independence or non-independence of the spirit we can apply this same method and then, in this way, come to know the particularities of spiritual phenomena and their originality and independence.

Once we study the particularities of the spirit and its effects, we see that these particularities do not coincide with the spirit being material. There are clear proofs and living examples of its non-materiality. We will briefly study this in the following:

Unity and Stability of the Personality

Even though we may have doubts about many things, there is no doubt about the fact that we exist. This is the lowest common denominator of the level of knowledge and awareness of each and every human being. Every human being knows that he or she exists. There is no doubt about this. We discover ourselves and we are certain about our existence. Our awareness of ourselves which is explained by the word 'I', is the clearest bit of knowledge we have and it requires no proof or reasoning.

On the other hand, we also know that the 'I' or 'self’ from the time of birth until the end of life was, is and will always be, one unit. Neither is change seen in it, nor can any multiplicity be assumed nor may it be divided up. It has no parts and essentially such a thing is not conceivable. And also even though we, throughout our lifetime, lose many of our characteristics or gain some, that which is described by the word 'I' has remained stable.

Now let us see what that stable unit which does not contain any change or multiplicity is. Is it a stable unit, unchangeable, without parts and indivisible or multiple cells in our body which every seven years totally changes? Is this ‘I’ or ‘self’ in every individual those very brain cells which according to Dr. Arani (who popularized Marxism 30 years ago in Iran), have a relationship among themselves which relates to both numbers and multiplicity and one which is destroyed when the cell dies and is re-established with the birth of new cells or is another creature involved?

If the 'I' of each individual consists of cells and their time-place relationship, a 70 year old human being will at least 10 times during his lifetime become other than that 'l' and his 'I' will have changed. Each person, then, would contain innumerable parts.

It is sometimes said that physiology has proven that the brain cells are stable and that these cells every so often are enlarged and then reduced in size but they do not change in number. The spirit has the same characteristics as the brain. As the cells of the brain are stable, and never decrease or increase, it would appear that the spirit is also a stable form.

But attention must be paid to the fact that that which has been proven by physiology is the following: The numbers of the cells of the brain do not increase or decrease, not that the atoms which formed them do not change. Thus the brain cells are also not stable and like the other cells or the body, every seven years give their place to new cells. In addition to this, these explanations can never describe the unity of the personality of the human being.

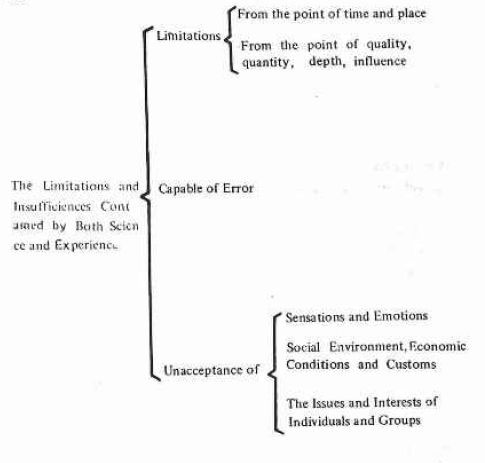

This particularity (the unity and stability of the self) makes us turn our attention to the non-materiality of the spirit. This indication alone is sufficient so that it becomes clear that the claims of Mr. Arani that "science has drawn a circle of destruction upon the existence of the spirit as an independent entity," Is nothing other than an absurd slogan. Science in this area has no right to give either a negative or positive answer because science has greater humility than to negate something which is beyond its domain.

Greater still, experimental sciences are not able to negate or affirm any phenomena whether it be material or non-material. They can never bring proof to negate the existence of something. The only conclusion that science and experience can bring is that in such and such an area of experiment, such and such was not found. It is clear that the non-finding and lack of awareness of the existence or non-existence of a phenomenon in no way proves its existence. From what has been said it becomes clear how absurd the words, "until the time does not come that we can cut the spirit with a knife, we will not believe in it," are.

The Substance of Perception

One of the spiritual phenomena is perception. The particularities of perception make the subtraction of the spirit and spiritual phenomena manifest. In order to make this clear, we will do a quick study of the substance of perception.

Every material creature has three characteristics: place, change and being capable of division. Now it must be seen whether or not any of these three characteristics can be found in the sense of perfection or not. If these three characteristics exist in the sense of perception, it is a material thing and if the sense of perception does not contain these three characteristics, it is clear that the proof of the non-materiality of perception has been proven. Now we will turn to each of these three and weigh them carefully with perception.

Place

Many times thousands and even millions of people have participated in demonstrations. Perhaps you have stood aside and watched the people. As far as the eye can see you are surrounded by people who are in motion, shouting slogans, fists clenched, they put the responsibilities or their school of thought on display. Look carefully. Do you perceive the multitude of people who have participated in the demonstrations? Have you ever thought about the place of all these people? Is it possible that these great forms which require hundreds of kilometers of space will fit into the small space of brain cells? Without doubt, these forms of ours exist and non-material organs of outs can hold them because it is not possible to have such large forms fit into the small cells of the brain.

Is it possible that the concept of external creatures be minutely reflected in our eyes through our nerve cells and our mind conceive of its size and we think that we have seen something in the size that it really is.

But we must recognize the fact that these words can in no way prove that the form of our perceptions has a place because, assuming this, we ask: Where is the great form which our mind itself has enlarged? If this great form which we perceive be material, it needs a place whereas our brain and our nerve cells do not have the capacity to give a place to it. Thus perceptions do not have such a place.

Change

With a bit of care and attention, we arrive at the conclusion that perceptions are not capable of change and cannot be because if perceptions were capable of change, they must, like other creatures, change and be destroyed. With the passing of time, color changes and takes on another form. This does not make sense that no perceivable stable form remain in the mind of the human being.

It is clear that our mental form, after the passing of many years, remains the same as it was to begin with and we can once again recall it. For instance years ago we learned that Aristotle was the student of Plato. If perceptions were capable of change, this fact must later take a different form. Even the suggestion of something like this makes us laugh. Thus perceptions do not change.

The Acceptance of Division

Conceive of a two meter long piece of wood. Now divide that into two parts. Look carefully. You can never cut that piece of wood which you conceived of. Why? If you were to really divide that wood into two parts, the perception of your mind would still contain the two meter long, piece of wood and you have only conceived of two pieces of wood, each one meter long.

The best proof is when you are asked, "What did you divide up?" You answer, "I divided up the two meter piece of wood into two one meter pieces." The very indication of yours to the two meter piece of wood which you first conceived of, still remains in your mind. Thus, it has not been divided. Look at other perceptions. They are the same. Thus perceptions do not accept division.

Now that we know that none of the three conditions of materiality exist in perceptions, we can consciously make the judgment that perceptions are not material. Thus now that it is clear that perceptions are non-material phenomena, we can conclude that other than the human body which contains the characteristics of materiality, there must be another dimension so that the person observing these non-material phenomena (perceptions) exist within the human being. That is that very thing which we call the incorporeal spirit.

Summary of the Lesson

1. A discussion of the resurrection can be divided into three sections: The eternality of human beings, the possibility of the resurrection and proving resurrection.

2. The two-dimensionality of human beings is accepted by all schools of thought whether they be material or nonmaterial ones and they only differ as to the authenticity of the spiritual dimension.

3. The spirit or self of the human being which is contained with the word 'I' has unity and stability and this is the greatest reason for its being an incorporeal entity.

4. Experimental sciences for two reasons cannot deny the incorporeality of the spirit. First, the spirit and spiritual phenomena are non-material and experimental facilities are only material places to study the effect of material things. Second, the only thing which science can prove is that it has not discovered the spirit and incorporeal things and this does not prove their non-existence.

5. Perceptions or our mental images neither have place, accept change nor are they divisible. Thus they arc not material and they tell of the existence or an incorporeal thing called spirit.

Questions to ask yourself

1. What is the opinion of materialists about the spirit and spiritual phenomena?

2. Can experimental sciences make judgments about things like the spirit? Why?

3. Which one of the characteristics of the spirit does not fit into its being a material thing?

4.Why are perceptions incorporeal substances?

0%

0%

Author: Laleh Bakhliar

Author: Laleh Bakhliar