2. Books of mathematical geography

Mathematical geography essentially consists of representing the inhabited world by means of a grid based on lines of latitude and longitude that have been defined by astronomical measurements. This science reached the Arab world following the translation from Greek to Arabic of works by Ptolemy and others, in particular, the Zij (astonomical almanac) of Thaeon of Alexandria, the book al-Mijisti, which was translated between 175 and 180 hijri, and the work al-Jughrafiya, which was translated once by Ibn Khurdadhdhbih and either twice or three times by both Yaqub ibn Ishaq al-Kindi and Thabit ibn Qurrah al-Harrani.

During the rule of the ‘Abassid Caliph al-Mamun (d. 218/833) an astronomical observatory was founded in the Shamashiyah quarter of Baghdad. Al-Mamun ordered the astronomers working in the observatory to devote themselves to testing the claims made in Ptolemy’s Zij and in al-Mijisti about the movements of the sun and other celestial bodies. As a result, numerous astronomical tables, or zij, were published which acquired the suffix, mumtahin, or ‘approved’. The scientists associated with this movement were known as the ‘masters of approval’.

All of these zij have since been lost except for the material which was appropriated from them by later authors for use in their own work; writers such as al-Masudi

and Abu ‘Abdallah Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr al-Zuhari (sixth century hijri).

There is, however, an example of such zij to be found in the Escorial Library in Spain, the only remaining fruit of the astronomers of this period to have survived until the present day. This can be found under reference 924 by a writer of Persian origin, Yahya ibn Abi Mansur (d. c. 215/830). In 1986, Fuat Sezgin produced a facsimile edition of this work under the title al-Zij al-Ma’muni al-Mumtahin.

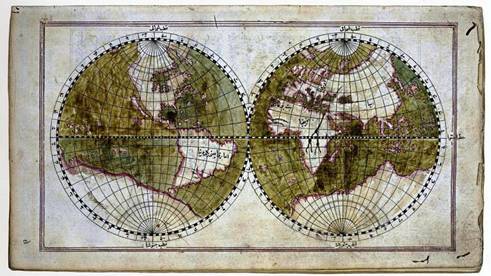

One important outcome of this enterprise was the image of the world that al-Mamun ordered 70 astronomers to create for him, an image which constitutes one of the greatest Muslim achievements in the history of science. The one surviving copy of the book, Masalik al-Absar fi Mamalik al-Amsar by Ibn Fadlallah al-Umari, kept in the Ahmet III Library in Istanbul (cat. no. 1/2797), contains an illustration of the al-Ma’mun map of the world dated 740/1340 (pp. 293-294).

Detail of the Map of the World made by the geographers of the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mamun (813-833)

One of the most important sources of mathematical geography, which had a profound influence on subsequent developments in the science, is Surat al-Ard by al-Khwarizmi.

Furthermore, no work on astronomy or mathematical geography that combines a scientific approach with a detailed commentary has had as triumphant an impact as al-Zij al-Sabi, which was published between 1899 and 1907 by Carlo Alfonso Nallino.

The zij completed by Abu al-Hasan ‘Ali ibn Yunus al-Sadafi in Cairo was based on work began in 380/990 in the observatory on the Muqattam hills that was to become the Dar al-Hikmah (House of Wisdom) founded in 395/1005 by the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim. This work was always associated with Hakim’s name and became known as al-Zij al-Hakimi al-Kabir. Today, there only remains a number of incomplete manuscripts of the work. Indeed, only a few short fragments of it have been published, though part of it was also translated into French by Caussin de Percival in 1803-1804.

Arabic geographical works written around the third and fourth centuries hijri can be divided into two broad categories. The first comprises work by scholars who wrote about the geography of the world and included detailed descriptions of the Islamic realm, dar al-Islam. There were also works on astronomical, physical, human and economic geography by writers such as Ibn Khurdadhdhbih, al-Yaqubi, Ibn al-Faqih and Qudamah ibn Jafar al-Masudi. This group is often known as the ‘Iraqi School’ since most of the works were produced in Iraq and the majority of the geographers were Iraqi.

A map by Abu Zaid Ahmed ibn Sahl al-Balkhi (850-934), a Persian geographer who was a disciple of al-Kindi and also the founder the“Balkhī school”

of terrestrial mapping in Baghdad. Picture displayed on“Old Manuscripts and Maps from Khorasan”

.

The second category comprises work by such writers as Abu Zayd al-Balkhi, al-Istakhri, Ibn Hawqal and al-Muqaddasi al-Bashshari that dealt with the Islamic territory alone, describing every region individually. No countries outside the Islamic world appear in these works unless they happen to be adjacent to Islamic areas.

The literature of this ‘classical school of Islamic geography’ provides us with the most favourable description of the Islamic world since it relies on material that was either a first-hand account of the author’s travels throughout many different areas and regions, or was based on what could be gathered from people who hailed from the places described. Commentaries were added to these accounts to provide further information - on populations, systems of transport and life in general - to provide an overall picture of political, social and economic life. The works of this school are linked to a series of maps to which Kratchkovsky has given the name ‘the Islamic Atlas’, maps which represent a high point of achievement in the art of mapmaking or cartography by Arabs and Muslims.

This ‘Atlas’ always contains 21 maps, produced in the same order, beginning with the circular map of the world otherwise known as the ‘al-Ma’mun map’. The main intention of the atlas is to depict the ‘Islamic world’, in accordance with the work of al-Istakhri and Ibn Hawqal in their specific way.

Abu Zayd al-Balkhi (d. 322/934) was the pioneer of this school. His book, Suar al-Aqalim, was written in 308/920 or shortly thereafter. Unfortunately, there is no surviving copy of al-Balkhi’s book available to us today, nor of any manuscripts belonging to the period dominated by al-Istakhri. De Goeje’s (1836-1909) belief that al-Istakhri’s book - which was finished between 318/930 and 321/933, and therefore during al-Balkhi’s lifetime - resembles an extended copy of al-Balkhi’s book does, moreover, seem reasonable.

The classical school placed a great deal of importance on producing an accurate representation of the Islamic realm, the dar al-Islam, but writings were more approximate about areas far from the centre, such as Iran and the Maghrib. The work of Ibn Hawqal was an exception, however, since he was the first to provide geographic accounts of the countries of the western Islamic world, the Maghrib, as can be seen from his book, Surat al-Ard. Editions of the latter have been prepared by both de Goeje and Kramers and a comparison of the two is valuable. There is a detailed description of the Beja region and its history, and of Eritrea which includes the names of over 200 Berber tribes, as well as a detailed description of Sicily.

Ibn Hawqal’s book, moreover, provides us with one of the most detailed accounts of Andalusia during the Umayyad period. This has led a good number of researchers to speculate that Ibn Hawqal was a spy for the Fatimids. In addition, Ibn Hawqal’s description of Isfahan represents the most important contribution to this literature on the eastern part of the Islamic world.

10th century map of the World by Ibn Hawqal.

The Dutch orientalist Michael de Goeje (1836-1909) was in charge of directing the Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum project, which between 1870 and 1894 published volumes of works by the most important writers of the classical school: al-Istakhri, al-Muqaddasi al-Bashshari, Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamdani, Ibn Khurdadhdhbih, Qudamah ibn Ja’far, Ibn Rustah, al-Ya’qubi and al-Mas’udi. In 1906, he also published Ahsan al-Taqasim by al-Muqaddasi al-Bashshari based on a new manuscript.

To edit the texts he published in the Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum, de Goeje relied on the manuscripts available at the time, however limited they were in number. The years immediately following de Goeje’s death, however, witnessed the discovery of a large number of manuscripts produced by the classical school including 12 works discovered in the libraries of Istanbul alone, some of which are very old indeed. The discovery of all these makes a compelling argument for the publication of a new edition of the first parts of the Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum, which would take into account the sources used and would also compare the extracts copied into later works with the original sources now available in the newly discovered manuscripts. To this end, in 1938, J.H. Kramers produced a second edition of Ibn Hawqal’s al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik with the title Surat al-’Ard, which was based on a manuscript from the Topkapi Palace Library, in Istanbul (ref. 3346). This is an early manuscript dated 479/1086. Another edition of al-Istakhri’s al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik was published by Muhammad Jabir al-Hini in 1961.

The Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum (BGA) is a series of critical editions of classic geographical texts written by several of the most famous Arab geographers.

Among the books published by de Goeje was Mukhtasar Kitab al-Buldan by Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamadani. The text studied was an abridgement made in 413/1022 by Abu al-Hasan ‘Ali ibn Ja’far al-Shirazi, who may have been the same copyist who transcribed the copy of Islah al-Mantiq by Ibn al-Sikkit, which is kept in the Kubrili Library, and the Diwan al-Buhturi, which can also be found there. Ibn al-Nadim mentions Ibn al-Faqih’s book, Kitab al-Buldan, which he describes as comprising about one thousand pages, and adds that he extracted the book from al-Nas and passed it on to al-Jihani.

When a copy of the work came into the hands of al-Muqaddasi al-Bashshari it was said to consist of five volumes.

Ibn al-Faqih probably wrote the book in about 290/903 but subsequently it seems to have disappeared for some time. During the beginning of the seventh century hijri, Yaqut al-Hamawi came across the original rough draft of the book from which he transcribed extensive extracts. In 1924, the Turkish scholar Zaki Walidi Tughan found the second part of the original draft, covering Iraq and the regions of Central Asia, in a geographic collection (ref. 5229) in the scientific library of Mashhad, Iran. When this collection was published in facsimile form by Fuat Sezgin in 1987, it also included an incomplete copy of the travels of Ibn Fadlan and two texts by Abu Dulaf Mas’ar ibn Muhalhil al-Khazraji al-Yunbui describing his journey to China and the travels he made in Azerbaijan and Persia in 331/941. It follows, therefore, that the version of Ibn Khurdadhdhbih’s al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik, which was published by de Goeje, contains only the first draft of the original book.

In addition to these literary works from the classical school that have survived and been published in the present day, there are also geography books from this period whose originals have been lost and which remain in a fragmentary form only where extracts from them have been copied by later writers. Ibn al-Nadim recalls that,“the first person to publish a book in the al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik and which he did not finish was Abu ‘Abbas Ja’far ibn Ahmad al-Marwazi”

.

Ibn al-Nadim adds that his writing was very good but that the author passed away in al-Ahwaz and he took the book to Baghdad and sold it to someone in the physician al-Harrani’s circle in the year 284/897.

This date coincides with the time that Ibn Khurdadhdhbih’s finished the first, and perhaps even the second, draft of his book of the same title.

Ibn Khurradadhbih’s Kitab al-Masalik wa l-Mamalik and part of the Kitab al-Kharajby Qudama ibn Jaʿfar

Al-Marwazi’s book disappeared after it was sold into the al-Harrani circle. History does not furnish us with any further information on his work other than meagre signs and excerpts, preserved for us by Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamadani and Yaqut al-Hamawi, that comment on Turkish tribes and a downpour of stones.

From these bits and pieces Kratchkovsky has concluded that al-Marwazi made a valuable contribution and left his mark on the geography of Central Asia!

A prominent practitioner of this period who left a deep impression on the growth and development of Arab geography was the writer Abu ‘Abdallah Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Nasr al-Jihani. Al-Jihani was the wazir to Nasr ibn Ahmad al-Thani al-Samani, the ruler of Khorasan and, according to Ibn al-Nadim, published a title in the series al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik, probably before 310/922.

Al-Muqaddasi mentioned that he saw this work, in seven bound volumes, in the ruler’s archives

but unfortunately it is no longer to be found. Since al-Jihani was a government official employed in Bukhara when he wrote his work he was able to extend his area of research into Central Asia and the Far East. Al-Jihani’s book has been used by a large number of Arab geographers and, according to al-Mas’udi, it was:“a description of the world and news of what it contains in terms of wonders and cities and civilisations and seas and rivers and the states and their populations and, apart from this, strange news and fabulous stories”

.

The information that al-Jihani provided on the regions, cities and towns of Central Asia was al-Idrisi’s prime source for his description of the area in his book, Nuzhat al-Mushtaq.

While all the al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik books mentioned above were written in Iraq and Iran, another geographer living in Egypt during the early part of the Fatimid era, al-Hasan ibn Ahmad (Muhammad) al-Muhallabi, wrote a book of al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik for the Fatimid Caliph al-’Aziz bi-Allah, which was later known simply as ‘al-’Azizi’. Al-Muhallabi’s book provided the most important source upon which Yaqut al-Hamawi drew when writing about Sudan; he quoted from it on more than 60 subjects. Al-Muhallabi did not, however, confine himself to the subject of Africa alone and Yaqut was to return time and again to his work to check on a wide variety of matters.

Yaqut also visited al-Muhallabi informally and recorded the personal details of their meetings for prosterity.

The loss of al-Muhallabi’s work is particularly sad. Yaqut did not preserve it for us, though he mentions it 60 times, nor did Abu al-Fida’, who mentions it on 135 occasions, though he did use a number of excerpts from it ranging from the extremely short to the very long. It is evident that these two writers considered al-Muhallabi to be among the greatest of geographers. While Abu al-Fida’ referred to al-Muhallabi only in terms of his commentaries on the countries of the Islamic world, from the excerpts which appear in Yaqut al-Hamawi’s work we can ascertain that in his book al-Muhallabi crossed the borders of the Islamic world and ventured into neighbouring lands.

In the summer of 1957, Salah al-Din al-Munajjid found a part of this lost book in the Ambrosiana Library in Milan, where it was discovered within a collection of Yemeni material. It had been transcribed by Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Kala’i (d. 404/1013 or later) and begins:“Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Kala’i: Taken from a book of the ‘Azizi al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik, a work by the writer al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Muhallabi”

. Al-Kala’i had transcribed sections on Jerusalem, the state of Egypt and a description of Damascus.

Al-Muhallabi’s book is important for its direct knowledge of the rule of the Tamurlanes and was used as such at the beginning of the ninth century hijri, but it was also relevant given it provided material of a geographical nature.

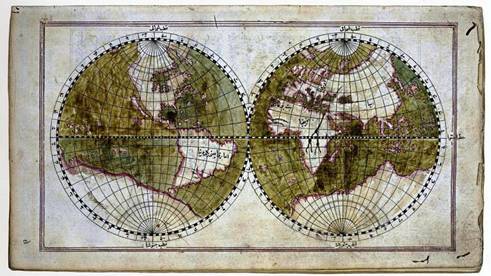

World Map, Müteferrika edition of Tuhfat al-Kibar, Topkapi Museum Library

While al-Muhallabi was one of the first geographers to provide a description of Sudan, another account is to be found in the work of the Egyptian, Abu Muhammad ‘Abdallah ibn Ahmad ibn Sulim al-Aswani; Akhbar al-Nubah wa al-Maqurah wa ‘Alwah wa al-Bujah wa al-Nil wa Min ‘Alayh wa Qurb Minh. Al-Aswani lived around the middle of the fourth/tenth century and was dispatched by (and on written order of) the Fatimid ruler, Jawhar al-Saqlabi, to the Nubian King Qibirqi. He was entrusted with the tasks of explaining Islam to King Qibirqi and of improving the settlement of the tribute that the kings of Nubia were expected to pay annually to the rulers of Egypt. Al-Aswani’s mission to Nubia appears to have taken place in the period between 358 hijri (the date of Jawhar’s arrival in Egypt) and 363 hijri (the arrival in Egypt of his successor, al-Mu’az).

Al-Maqrizi records that al-Aswani dedicated his book to the second Fatimid caliph, al-’Aziz bi Allah, who ruled between 365 and 386 hijri.

The book itself contains a brief account of all the places that he visited and the people who inhabited them. His description of the Nile constitutes a unique contribution to the literature of early Arab geography in that it extended Arab knowledge of the upper reaches of the river. It would appear that this work, which is also now lost, is not known outside Egypt, although al-Idrisi’s description of the course of the upper Nile is clearly indebted to a transcription of these sources; clearly then, al-Idrisi must have had it close at hand. Yet today, we only know about al-Aswani’s work from the citations transcribed from it by three Egyptian writers: al-Maqrizi, Ibn Iyyas and al-Manufi.

0%

0%

Author: Ayman Fuad Sayyid

Author: Ayman Fuad Sayyid