5: PAKISTANI MADRASAS AND RURAL UNDERDEVELOPMENT

An empirical study of Ahmedpur East

Saleem H. Ali

Introduction

Islamic educational institutions have come under intense public scrutiny in recent years because of their perceived link to militancy. However, much of the research thus far has relied upon anecdotal accounts and investigative journalism, rather than rigorous social science. This study acknowledges and respects that madrasas are a vital institution in Islam and indeed in many cases even non- Muslims have sent their children to madrasas because of the high quality of education (such as those in West Bengal, India). However, Pakistani madrasas have endured much interference from various sources that have led to certain differences in operational style and function as compared to their historical predecessors. The aim of this chapter is to bring integrative and objective clarity to the issue – moving away from the propagandist negative accounts about madrasas as well as the revisionist positive accounts or diminution of their impact on Pakistani society. Madrasas do indeed have a significant impact on Pakistani society – both positive and negative. This study aims to provide an empirically grounded analysis of madrasas in Pakistan, thereby informing the larger discussion of the role of Islamic education in conflict causality.

While this topic has received widespread media coverage and has been discussed within the broader context of radical Islamization, the research thus far has generally been predicated on observational accounts and anecdotes that range from strongly positive to vehemently negative. Akbar S. Ahmed (2002) considers madrasas to be a “cheaper, more accessible and more Islamic alternative to education.” Singer (2001) calls them a “displacement of the public education system.” Jeffrey Goldberg (2000), even before 9/11, terms them as a means of “education of the holy warrior.” Jessica Stern (2004), while describing them as emblematic of “Pakistan’s jihad culture,” uses epithets and subheadings like “schools of hate” and “Jihad International Inc.” Andre Coulson (2004) refers to madrasas as “weapons of mass instruction.” Most consequenS tially, the 9/11 Commission refers to madrasas as “incubators of violent extremism.”

Recently, there have also been revisionist accounts of madrasa prevalence that question the sensationalism of some media reports. Even some journalists and travel writers have taken exception to this sensationalism and begun to publish more humane accounts of madrasas (Dalrymple 2005). Of particular note has been a controversial study prepared with World Bank funding that questions the need for such anxiety over madrasas by providing data that suggests their limited prevalence within the larger context of Pakistani schooling (Andrabi et al. 2006). This study contends that much of the information in reports and government documents, including the 9/11 Commission report of the USgovernment,

have largely predicated their estimate of madrasa enrollment on anecdotal accounts. In particular, the World Bank study targets the work of the International Crisis Group – ICG (2004) for perpetuating an error in calculation of madrasa percentage.

While there was indeed a decimal calculation error in the ICG report, the World Bank study misses the major point that the exact number of madrasas might not necessarily be consequential in terms of conflict linkages.

Unlike the World Bank study that relied on Pakistan household census data and conducted some of its own household surveys to ascertain from families where they were sending their children for schooling, our study relies on exhaustive establishment surveys of each madrasa in Ahmedpur sub-district in Punjab. We thus get first-hand information from the schools themselves about enrollment, funding sources and connections with sectarian activity. The usual critique of establishment surveys in this context can be that schools might not provide accurate information about enrollment for strategic purposes of either gaining more government funding or diminishing scale to avoid political suspicion. However, we relied on local staff from villages in the area to conduct the surveys to provide quality assurance. We also supplemented our quantitative analysis with detailed interviews at the local and regional level with clerics, government officials,madrasa

students, researchers from academia, journalists, and representatives from non-governmental organizations. Our aim is to thus provide an integrative, nuanced and prescriptive analysis that can have greater policy relevance and applicability.

Definition

The word “madrasa” is derived from the Arabic word dars, meaning lesson. In contemporary Arabic, the word “madrasa” means “center of learning.” The Arabic word madrasa generally has two meanings: in its more everyday usage, it means school and in its secondary meaning, it is an educational institution offering instruction in Islamic subjects including the Qur’an, the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, jurisprudence and law. Madrasas are in some ways analogous to a seminary in Christian tradition (Armanios 2003).

Madrasas generally provide free religious education, boarding and lodging and are in many contemporary cases patronized by low-income families. However, some rich and middle-class families also send their children to madrasas for Qur’anic lessons and memorization where they are usually day students. A madrasa student learns how to read, memorize and recite the Qur’an properly. Madrasas issue certificates of various levels. A primary or part-time religious school and one focused primarily on Qur’anic recitation and memorization is often referred to as a maktab (derived from the Arabic word kataba, to write), and an integrated school with various levels is simply called a madrasa. While the distinction between a maktab and a madrasa may be important in some contexts – often both are affiliated with mosques and religious institutions and may share teachers. What is also significant is that many madrasas are residential and often these play a more significant role in shaping the personality of students. Our study thus tries to differentiate between residential and nonresidential madrasas where possible.

At the time of independence in 1947, there were only 137 madrasas in Pakistan. According to a 1956 survey, there were 244 madrasas in all of Pakistan (excluding East Pakistan which became Bangladesh in 1971).

While there is no comprehensive census of madrasas across Pakistan at present, a reasonable estimate based on our review of multiple empirical and journalistic sources would suggest that there are between 12,000 and 15,000 madrasas in Pakistan.

However, as noted earlier the absolute number of madrasas across Pakistan is not consequential for understanding any conflict linkages. Instead, we focused on a case study of particular relevance to conflict dynamics and the demographics within the case – in particular the relationship between the various Islamic sects in this case.

Case analysis

The data on madrasas was gathered through primary field visits by individual survey data collectors. Statistics on government and private schools were obtained from secondary sources such as the UNESCO Education Atlas or the Ministry of Education. An effort was made to verify these numbers through cross-checking with local officials and civil society groups. A form was devised for the purpose of data collection from each madrasa and contained the following information:

1 Name of Police Station [key unit of administration and research analysis].

2 Name of Madrasa.

3 Name of In-charge/Manager.

4 Location (village/street).

5 Year of establishment.

6 Number of students-residential and non-residential.

7 Sect to which Madrasa belongs.

8 Whether receiving monetary aid from Government (from Zakat fund).

Representatives of the Special Branch (provincial intelligence agency), local police and administration were also consulted for determining sectarian involvement of madrasas.

Ahmedpur case analysis

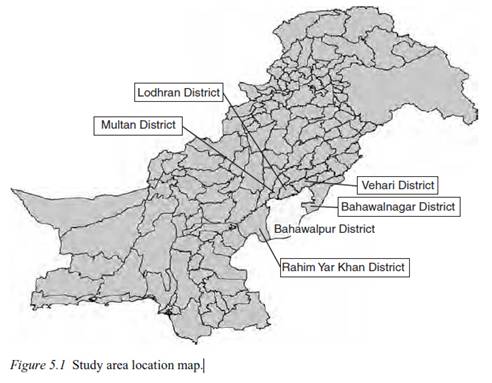

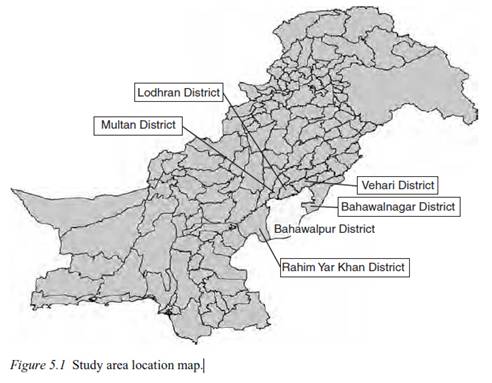

Ahmedpur East Sub-division, in Bahawalpur district, of Punjab (Pakistan) (Figure 5.1) has an area of approximately 6,000 sq. kilometers, and, of a population of 1,000,000, approximately 800,000 is rural and200,000 urban.6 Ahmedpur East

comprises 187 villages, and six police stations. The police station is an administrative unit for law enforcement based on demographic patterns. The sub-division is situated on the left bank of river Sutlej in the southern-most part of Punjab (Figure 5.1).

During the last decade, this region has been the locus of considerable sectarian violence. The region has a history of many fatal and violent incidents involving the Sipah-i Sahaba Pakistan (SSP-Deobandis) and Tahrik-i Jaffariyya Pakistan (TJP-Shias). Ahmedpur East Sub-division is considered to be a stronghold of the SSP – the strength of this organization here can be gauged from the fact that during the national elections of 1993, the SSP candidate gained approximately 24,000 votes, despite the fact that the candidate was from another province and had no direct connection with the area.

Figure 5.1 Study area location map.

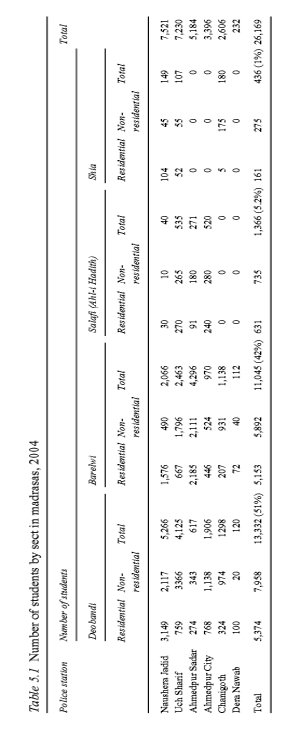

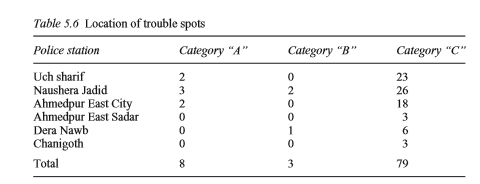

The total number of madrasas in the Sub-division is 363; of these 166 belong to the Deobandi sect, 166 to the Barelwi, 21 to the Salafi (Ahl-i Hadith) and ten to the Shia (Ahl-i Tashi) sects. Percentage-wise, distribution between the different sects is 45.8 percent, 45.8 percent, 5.7 percent, and 2.75 percent respectively. Only 9.3 percent of the madrasas (34 out of 363) are receiving monetary aid from the Government/Zakat fund. Table 5.1 summarizes the results of the survey conducted for this study in Ahmedpur by sects.

An analysis of the growth of the madrasas shows that prior to 1975 and 1980 there were 82 and 124 madrasas respectively in Ahmedpur East. Much of the growth was experienced between 1980 and 1995, the growth of madrasas has greatly slowed down after 2001 – only eight new madrasas were set up between 2001 and 2004. This slowdown in growth can be attributed to a general administrative policy wherein new madrasas are being registered after an inquiry, and a ban imposed on the registration of new madrasas was in effect until September 2004, when it was lifted by authorities. However, the madrasas established earlier are still largely unregistered and very little effort is being expended in trying to register them.

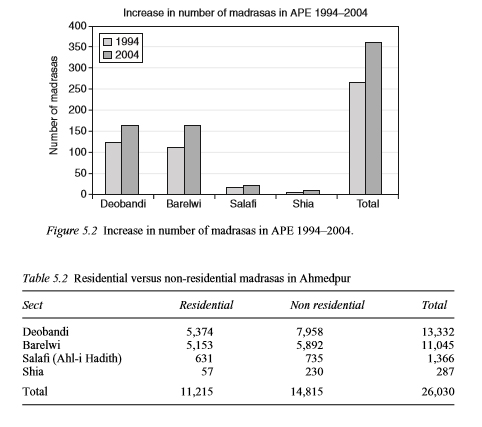

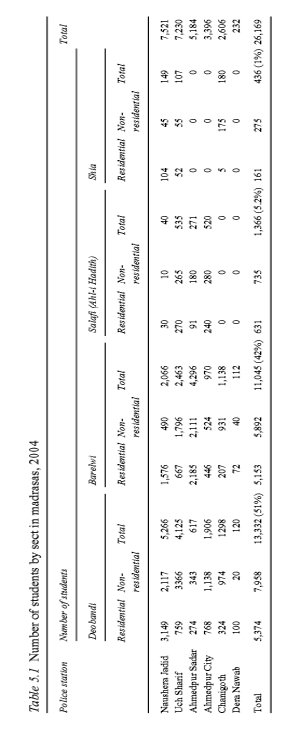

It is worthwhile to compare this data with the survey done by the field research coordinator of this study in 1994, in the same area – this provides a rare comparison of data pertaining to the same area after ten years. Figure 5.2 provides the ten-year growth comparison for madrasas in this Sub-division.

During the last ten years, the number of madrasas has increased from 266 to 363. There has been a marked increase in the number of Deobandi and Barelwi madrasas. However, the rate of increase in Barelwi madrasas has been higher in the last ten years. This finding also matches the information gathered during the interviews which suggests that the Barelwi movement has also gained momentum as a foil to the rise of Deobandi madrasas. The coverage of Zakat to madrasas during this period remained similar, i.e. around 9 percent of Madrasas get monetary support from the Zakat system.

The study shows that a major concentration of these madrasas is in the area of the Police Station Uch Sharif and Naushera Jadid. These two police stations account for 55 percent of the madrasas and 58 percent of the students in the Subdivision. It is worth mentioning that 68 percent of the madrasas in Police Station Naushera Jadid are Deobandi, and incidentally this area is a main support base of the SSP. The same can be said about the madrasas situated in villages in the northern half of Police Station Uch Sharif. Table 5.2 shows the distinction between residential and non-residential madrasas in Ahmedpur.

Almost 40 percent of the students were living in the madrasas, and Deobandi madrasas, although equal in number, had greater student enrollment, particularly of residential students.

Table 5.3 shows the registration status of madrasas with the government. Only 39 madrasas out of 363 were registered. The registration is undertaken under the Societies Act of 1860, which was previously performed by the Registrar Joint Stock companies on the report and clearance by the district administra tion. After the administrative reforms called “The Devolution Plan 2001,” the authority to register any organization under the Societies Act 1860 has been delegated to the Executive District Officer (Finance and Planning) in the province of Punjab. In the other provinces this authority still remains with the Directorate of Industries at provincial level.

Table 5.1 Number of students by sect in madrasas, 2004

A greater proportion of the Barelwi and Salafi/Ahl-i Hadith madrasas are registered. As a general trend, larger madrasas, having an elaborate infrastructure and assets are registered while smaller madrasas (with fewer than 100 students) are mostly not registered.

State of public education and madrasas

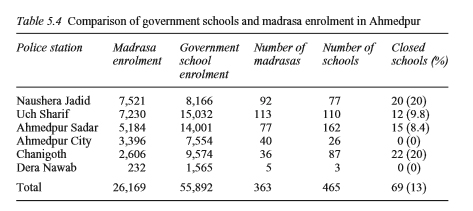

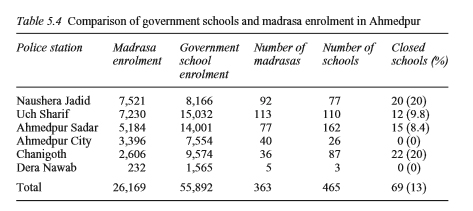

Schooling options are an important variable to consider in understanding madrasa prevalence. Table 5.4 shows a comparison of the number of madrasas and student enrollment in different police station areas. It also shows how many schools are closed. These figures pertain to government schools only and include boys’ and girls’ schools of primary, middle and higher standard, whereas madrasas data shows only male students studying in madrasas since there were very few girl students in madrasas of Ahmedpur East.

Figure 5.2 Increase in number of madrasas in APE 1994–2004.

Table 5.2 Residential versus non-residential madrasas in Ahmedpur

Table 5.3 Registration status of madrasas

The data shows that, as compared to 363 madrasas, there are 465 schools, of which 69 (almost 13 percent) are closed due to non-availability of teachers or teacher absenteeism. A total of 55,892 boys and girls were studying in public schools as compared to 26,169 in madrasas.

It is worth noting that two police station areas having fewer madrasas have comparatively more schools and hence more student enrollment. However, in the Police Stations Nushera Jadid and Uch Sharif the number of madrasas is higher than that of government schools. The student enrollment in Naushera Jadid between madrasas and public schools is quite comparable. If one accounts for the girl students, the number of students studying in madrasas and public schools becomes almost equal.

Data on private schools was also obtained from a local association of such schools (the government does not keep any detailed records of private schools).

Only aggregate data for the entire Sub-division was available and indicated that as of December 2004, there were a total of 17,137 students in 95 private schools.

Urdu-medium students account for 15,842 of this amount while there are only 1,295 English-medium students.

Is there madrasa involvement in sectarianism?

The ultimate aim of this study is to question the perceived linkage of madrasas to sectarian violence. This aspect of the research was assessed using proxy indicators – certain features or modes of behavior were picked to classify a madrasa as being involved in sectarianism. The following are some of the indicators used for the purpose:

1 Any madrasa, which is visited by leading sectarian leaders, whose documented speeches have clearly incited violence towards other sects (records of particular events were gathered to assure quality of the data).

Table 5.4 Comparison of government schools and madrasa enrolment in Ahmedpur

2 If the students/in-charge of a madrasa participate in sectarian processions or gatherings as documented by the police authorities (detailed records are kept by the police authorities regarding apprehensions from each institution).

3 If the management of a madrasa lobbies for, or provides leadership to sectarian issues (documented through distribution of material at the madrasa and sermons at adjoining mosques).

4 If managers or students were involved in reported violent sectarian crimes (there will be a more specific analysis of this in Table 5.6).

Madrasas exhibiting any of the above features were categorized as positive for sectarian activity. The categorization was done after extensive interviews with local police officials, district administration officers, mosque imams and local community leaders.

Madrasas situated in the Police Station Naushera Jadid, Uch Sharif and Ahmedpur Cityhave

an involvement rate of 100 percent, 57 percent and 45 percent respectively. Deobandi and Shia sects have very high rates of involvement in violence and sectarianism. Traditionally Deobandi and Shia sects are in most acute conflict; hence, we observed that madrasas from these two sects are overwhelmingly sectarian. However, Barelwi madrasas, which were traditionally very tolerant and non-confrontational institutions, have also started showing violent and sectarian tendencies. In many instances this is a response to violent and aggressive attitudes of some Deobandi institutions and their managers.

Based on police data categorization, Table 5.5 shows the involvement of madrasas in sectarian incidents in the region.

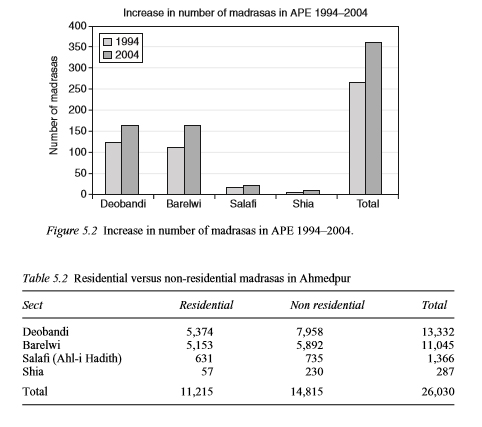

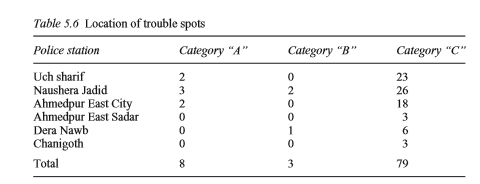

In addition, we also analyzed particular incidents of violence or “hotspots,” as they are labeled by local law enforcement authorities. The hotspots are administratively also called trouble spots. The local administration and intelligence agencies in consultation with local police authorities classify the trouble spots or hotspots in A, B and C category. This categorization of trouble spots is an administrative tool used by local police authorities for vigilance, monitoring of sectarian violence and local law and order. It is used for deploying personnel for the prevention of serious conflict on different religious occasions. The trouble spots categorization can be both general and day- or event-specific. This helps local police to monitor the situation and make adequate preventative measures.

Table 5.5 Madrasas involved in sectarianism

This categorization or classification is based on the following criteria.

Category “A”: Any location where a serious sectarian conflict has happened in the past, and resulted in the death of a person, is labeled “A” category. Such locations are specially monitored on national occasions and are closely watched by supervisory officers on religious events. At manyA

category trouble spots military or para-military forces are deployed beforehand.

Category “B”: These are locations where in the past there has been physical conflict between different religious sects. The reason could be the holding of a religious event on contested territory, or the route taken by the procession. These spots indicate areas of serious conflict but without loss of life.

Category “C”: These are locations where there is potential for clash or conflict, based on the fact that verbal brawls have occurred in the past, or rival sects have been agitating against each other through demonstrations.

In Ahmedpur East, there are 90 trouble spots of A, B and C category. More that 90 percent of these are situated in the police station areas of Naushera Jadid, Uch Sharif and Ahmedpur City. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Analysis has shown that there are eight “A” category trouble spots in Ahmedpur Subdivision; these are located in the Naushera Jadid, Ahmedpur East City and Uch Sharif police station areas. The trouble spots or hotspots are invariably situated in areas which have more concentration of Deobandi and Shia madrasas. A closer analysis and study of the background of trouble spots showed that management and students of particular madrasas were instrumental in the history of conflict pertaining to that trouble spot. Another finding is that the location ofA

category trouble spots is invariably linked to highly sectarian Deobandi and Shia madrasas.

The next question that we need to consider is what might be the underlying reasons for the high concentration of madrasas as well as sectarian activity in Naushera Jadid and Uch Sharif, which are relatively rural areas and not subject to the same urban violence pressures as Ahmedpur.

Table 5.6 Location of trouble spots

Environmental and developmental differentiation of sectors

In rural Pakistan and particularly South Punjab, political, economic and social power is closely linked to landownership. Access to land or landownership determines the social and political standing of an individual or a group of people in a society. Based on an analysis of landholding patterns from government records we concluded that 96 percent of the population of Ahmedpur holds less than five acres of land.

Extremist and sectarian groups and religious parties have larger followings in areas where local feudal landowners have been controlling political and economic (land) power. The districts of Jhang, Khanewal, Multan,Vehari

(Mailsi) Bhawalpur are all cases in point. This reaction has been more radical and severe in areas where the local political power was with Shia land gentry or those more inclined to worship near shrines (often of Barelwi persuasion).

Madrasas were frequently the focal point of this movement against the traditional feudal leadership, particularly where it was Shia. For the downtrodden and politically, socially and economically marginalized peasants, the religious political parties were a means of turning the tables on the traditional elite. The state functionaries were particularly receptive and obliging to religious/sectarian leaders, thus adding to their mass appeal. The disposition of the administrative machinery towards religious leaders, particularly those belonging to militant radical Deobandi groups, has been a post-Afghan jihad phenomenon. Many of the jihadis returned to their village bases and established madrasas as a means of livelihood. The administrative functionaries extended patronage to these groups accordingly. This phenomenon brought a fundamental change in the social standing of madrasas and their graduates since they began to symbolize a revolution against an oppressive feudal system.

In Ahmedpur East landownership patterns are also extremely asymmetric. Out of a total of 156,977 landowners, only 4 percent own more than five acres of land, whereas 96 percent of the land owners have less than five acres of land. In Pakistan the official economic subsistence holding size is 12.5 acres. This shows that an individual holding less than five acres is living at the margins and needs external assistance or extra employment to meet basic survival needs. In our survey area this phenomenon is seen across the whole Sub-division. However, we observed that in the Chanigoth and Ahmedpur East Sadar police station areas, although landholding patterns are similar, the phenomenon of sectarian madrasas is less prevalent. One reason could be the fact that the above two areas are near the national highway, thus giving many other economic opportunities and exposure. Further study, perhaps using anthropological methods, may be needed to obtain a more conclusive explanation to this observation.

Different environmental and developmental indicators were also studied to explore linkages between madrasa–conflict linkages and deprivation. Table 5.7 shows the electrification of the various areas studied.

Access to electricity is an important indicator of poverty and standard of living. Almost 13 percent of villages are without electricity, in 25 percent of the villages less than 25 percent of households have electricity,in

another 30 percent the access to electricity is available to 25–50 percent of households. The area of Naushera Jadid which is worst hit by sectarianism and proliferation of madrasas, in 75 percent of thevillages

electricity is available to less than 50 percent of households.

Table 5.7 Electrification in key study area locations

The availability of potable water through government-provided safe drinking water supply schemes was also studied. Out of the 185 villages in the Subdistrict only nine villages have drinking water schemes. Considering that the incidence of water-borne diseases is extremely high in the area, the unavailability of safe drinking water is a major developmental challenge. Here also we observed that not a single water supply scheme is provided in Naushera Jadid and the northern half of Uch Sharif, areas of higher sectarian activity.

The provision of road connectivity has also been documented. In terms of mobility and providing access to the market for agricultural produce, farm-tomarket roads are an important provision. Although generally better than other socio-economic indicators, approximately 20 percent of the villages are still not connected to the farm-to-market roads. The perennial shortage of irrigation water is one of the key factors contributing to the low productivity and poverty of the area. Scarcity indicators for the villages were developed based on municipal classifications. Given the semi-arid climate in this area, agriculture is highly dependent on irrigation water. Out of 185 villages in the region, 150 experience extreme water shortage. Only eight villages have no scarcity of canal water and another 25 villages have a mild shortage. In Naushera Jadid the water shortage is mostacute,

all 31 villages have extreme shortage of canal water.

In terms of agricultural productivity, although no major variation is seen between different regions of Ahmedpur Sub-division, the average yield of wheat and cotton is almost half of the average yields expected of subsistence farms.

The average yield of 15 maunds (one maund=40 kg) of wheat and 12 maunds of cotton is half of what some farmers get in the same Sub-division. This data shows that agricultural productivity in the region is at a sub-optimal or low productivity level.

As noted earlier, madrasas have been perceived as a counterweight to feudalism in Southern Punjab. Coupled with environmental resource scarcity and underdevelopment, the madrasas have provided a physical and emotional refuge for many families. Ahmedpur East is an example of this phenomenon. The political leadership here has for decades been with the Nawabs of Bhawalpur (based in Ahmedpur City and Dera Nawab) and the Makhdums of Uch Sharif (Gilani and Bukhari Shias). The religious leadership that rose from madrasas challenged these ruling families. One of the factors contributing to the growth and influence of madrasas in Ahmedpur East City, Uch Sharif and Naushera Jadid is the typical social response to feudal social structures described above. These are also manifest in some of the environmental and development indicators that we observed for the regions in question.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study finds that rural underdevelopment may contribute to the vulnerability of social institutions such as madrasas. However, poverty per se is not a sufficient condition for the co-option of educational institutions by extremists. Existing sectarian divides are sharpened by institutions such as madrasas which are often exclusionary of other religious interpretations. Young students under authoritative control of their teachers are easier targets of co-option by radical elements than the general public, and deserve to be considered for policy intervention.

However, such intervention will have to follow a theological path since madrasas are inherently religious schools and thus reforms would need to be introduced through scriptural exegesis rather than simply introducing parallel secular subjects.

Madrasas are an important social institution across the Muslim world and are often described by proponents as the nation’s largest network of NGOs (nongovernmental organizations). However, the noble purpose of education and enlightenment, for which madrasas were originally intended, has been challenged by various sectarian elements within Pakistan. This study finds evidence of linkage between a large number of madrasas and sectarian violence in rural Punjab. We also found that the number of madrasas has increased over a tenyear period and that in some areas they are competing with government and secular private schools for enrollment. Many madrasas are residential and cater to relatively poor students in these areas. However, in urban madrasas, this pattern is not always followed as affluent families may also send their children to madrasas for disciplinary and theological reasons.

Sectarian activity in areas of greater madrasa density per population size was found to be higher, including incidents of violent unrest. Unfortunately, most urban observers in Pakistan tend to cast aspersions on “foreign elements” for any sectarian activity, without conducting in-depth analysis of causality. While Iran has funded Shia madrasas and Saudi Arabia has funded Salafi and Deobandi madrasas, there is no other external linkage to be found with regard to the violence observed on religious festivals and other occasions. Sectarianism is a serious and palpable internal challenge for Pakistan, and madrasas in this case study were found to be contributing to this challenge. However, this is more of an internal challenge for Pakistan rather than a direct contributor to international terrorism. Indeed, most of the al-Qaeda operatives that have been apprehended did not attend madrasas and were often educated in Western schools. It is thus important to differentiate domestic sectarian activity and international violence.

There may be a connection between the two in some cases such as in Kashmir and domestic Afghan conflicts, but more generally, the two require complementary strategies rather than identical paths for resolution.

This chapter also looked at possible environmental and developmental factors that may be contributing to economic deprivation and consequential radicalization of the population. The continuing prevalence of the feudal elite and economic inequalityhave

given madrasas a greater sense of legitimacy as a social movement in this region. Areas of higher madrasa prevalence had lower development indicators, such as electricity or roads and access to natural resources such as water for irrigation. Inequality in land distribution patterns between ethnic groups can provide fertile ground for radicalization to take root. Comprehensive land reforms across Pakistan are also essential to reduce radicalization that stems from disenfranchisement of peasant communities by the feudal elite that seeks refuge in religious radicalism for a sense of worth. Such reforms can be undertaken through market mechanisms and instituted gradually to avoid capital flight.

Development of these areas may also reduce radicalization and open other career opportunities for madrasa graduates. Vocational training programs for madrasa graduates following their seminary education and clear ways for them to be channeled into such programs should be funded independently of the madrasas themselves. In addition, the economic disparities that are perpetuated by the feudal elite need to be addressed through establishment of trust funds for each village serviced from property tax revenues that the landlords must be obliged to pay in order to retain title to their land. While major land redistribution is unlikely to occur in Punjab, there can be better management of existing land-use patterns to ensure more equitable distribution of resources and local involvement in economic decision-making.

The governments efforts at “mainstreaming” madrasas, as exemplified through programs such as the “model madrasas,” is not likely to succeed because it is perceived as an external imposition. While the allocation of resources for madrasas, such as the Rs 1 billion allocated for madrasa reform announced on 7 June 2005 (20 percent of the entire budget for the education ministry’s public sector development program) is laudatory, these resources might be channeled more appropriately. Instead of trying to convert madrasas into conventional schools, there should be an attempt made to expose madrasa leaders to alternative voices of Islamic learning and facilitating dialog between various sects. Curricular reform would naturally follow from such interactions and could complement the vocational training programs for madrasa graduates mentioned above.

Just as there have been attempts at ecumenical dialog between faiths, a concerted and deliberate national dialog between Shias and Sunnis (and within the Sunni sub-sects) is essential. Apart from their educational activity, some of the larger madrasas also serve the purpose of providing theological opinions on various community concerns. Deliberative dialog on some of the issues that are raised by community members in these solicitations could be a formal means of initiating dialog between sects as well.

At the same time, violence and incitement to violence must be treated as any other law enforcement action. There should not be any exception made for particular establishments where communal violence is concerned as this sends a mixed message to agitators. While censorship of madrasa literature or any publications and sermons is to be avoided to preserve freedom of expression, the publication of erroneous data and inflammatory rhetoric that can be suggestive of violence is not protected under any freedom of expression legislation. Indeed, the role of the mass-media in instigating violence is widely documented in cases such as the Rwandan genocide and other cases (Schabas 2000). Hence, promoting a culture of responsible dissemination of information is essential in this context as well. Indeed, even in Islamic tradition, there are very strict injunctions and responsibility for giving inaccurate sermons and admonition for inciting violence. Such injunctions should be invoked in this regard. There should be closer scrutiny of any misinformation or incitement to violence in publications, particularly in areas of high sectarian activity.

The challenge of preventing co-option of Islamic institutions by external interests for political conflict, while preserving their independence and social service is reaching a critical juncture in Pakistan. A multifaceted strategy is essential to tackle this challenge – one that accepts the empirical insights that are provided by research and avoids sensationalistic or sanguine accounts of the problem.

Notes

23%

23%

Author: Jamal Malik

Author: Jamal Malik