Volume 16 Numbers 1 & 2

©The Author(s) 2014

A Learning Combination: Coaching with CLASS and the Project Approach

Sue Vartuli, Carol Bolz, and Catherine Wilson

University of Missouri–Kansas City

Abstract

The focus of this ongoing research is the effectiveness of coaching in improving the quality of teacher-child instructional interactions in Head Start classrooms. This study examines the relationship between two measures: Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) and a Project Approach Fidelity form developed by the authors. Linear regressions were used to investigate predictors of CLASS domain scores. The Project Approach Fidelity scores have positive predictive relationships to the CLASS domains. Higher Project Approach Fidelity scores predicted higher scores for the CLASS Emotional Support, Classroom Organization, and Instructional Support domains. Consistent with their findings, the authors recommend that use of the Project Approach be combined with attention to behaviors emphasized in the CLASS to help teachers intentionally improve instructional quality in prekindergarten classrooms.

Introduction

If you have benefited from free access to ECRP, please consider making a financial contribution to ECRP so that the journal can continue to be available free to everyone.

A goal for prekindergarten education today is to maintain high expectations for all children, while closing what is often called “the school readiness gap” associated with socio-economic status. Recent research indicates that both instruction and teacher-child interactions may be predictors of child outcomes (Bogard, Traylor, & Takanishi, 2008; Chien et al., 2010) and that there is considerable variation in the quality of instruction and teacher-child interactions in classrooms (Curby et al., 2009; Howes et al., 2008; LoCasale-Crouch et al., 2007; Pianta, 2005, 2006 ). Research also suggests that continued professional development and support for early childhood classroom teachers is needed generally to improve classroom quality and enhance children’s learning (Bogard et al., 2008; Lieber et al., 2009; Pianta, 2005, 2006; Pianta, Howes et al., 2005; Pianta, Mashburn, Downer, Hamre, & Justice, 2008).

In this article, we describe an ongoing study that combines coaching with implementation of the Project Approach and use of the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS), a standardized classroom observation instrument focused on teacher-child interactions (Pianta, LaParo, & Hamre, 2008). An interest in understanding and refining coaching strategies originated with a group of Head Start coaches who formed a community of practice with colleagues from two local universities. After being trained in the use of the CLASS as a professional development tool, the group decided to investigate how to support teacher-child interactions in the Instructional Support domain of CLASS, where scores had been lowest for the classrooms of the teachers being coached, as well as for classrooms observed in large national studies (Curby et al, 2009; Hamre & Pianta, 2005).

During the pilot year, coaches engaged teachers in side-by-side analysis of videotaped teaching practice using the CLASS Instructional Support domain as a framework. Coaches worked with teachers to set goals for improvement of specific teacher behaviors and provided support for achieving those goals. At the end of the pilot year, the group of coaches reflected on research findings to plan for the second year. Although results were promising and included significant shifts in CLASS Instructional Support domain scores, the coaches posited that the approach to coaching might be enhanced if teacher-child interactions were more closely connected to classroom curriculum. The Project Approach was selected as a curriculum element because of its sustained opportunities for investigation of worthy topics and the multiple contexts in which teachers and children can think together.

Helm and Katz (2011) propose that the Project Approach provides experiences that involve students intellectually and develop their dispositions to make sense of experience; to theorize, analyze, hypothesize, and synthesize; to predict and check predictions; to find things out; to strive for accuracy; to be empirical; to grasp the consequences of actions; to persist in seeking solutions to problems; to speculate about cause-effect relationships; and to predict other’s wishes and feelings (p. 4). The participating coaches noted that the emphasis on higher-order thinking skills and intellectual dispositions in the Project Approach aligned well with the CLASS Instructional Support domain (Pianta, La Paro, & Hamre, 2008). For example, teachers rated high in CLASS Instructional Support domain (Concept Development dimension) often engage children in discussions and activities that encourage analysis and reasoning. These teachers focus on problem-solving, prediction and experimentation, classification and comparison, and evaluation. They provide opportunities for children to brainstorm ideas, plan activities, and create products. They help children integrate concepts with related ideas, including previous learning, and relate concepts to the real world (p. 62). Teachers rated high in CLASS Instructional Support domain (Quality of Feedback dimension) also provide feedback that expands learning and understanding. They engage in back-and-forth exchanges with children, invite children to explain their actions and ideas, ask open-ended questions, and prompt children to explain their thinking (p. 69).

The coaches hypothesized that the high-level instructional interactions described in the CLASS Instructional Support domain would occur more naturally and frequently if teachers were engaging with children in the Project Approach. The coaches also read Helterbran and Fennimore’s (2004) proposal for an inquiry approach to professional development in which teachers become researchers of their practices by documenting and reflecting on their work. The coaches hoped that the Project Approach would provide a context that would prompt both the coaches and the teachers to become more observant and reflective in their thinking about children’s intellectual development (Catapano, 2005).

Review of the Literature

To provide background and context for this study, we review research and professional literature in four areas: professional development and the CLASS; coaching; the Project Approach; and teacher beliefs.

Professional Development and the CLASS

In-service teacher professional development has been shown to have great potential to improve the quality of classroom interactions and to enhance outcomes for children (LoCasale-Couch et al., 2007; Mashburn et al., 2008; Pianta, 2005, 2006; Pianta, Mashburn et al., 2008). Recent research indicates that when teachers intentionally focus on teacher-child interactions, children’s behavioral regulation and cognitive competencies improve (Downer et al., 2011; Lieber et al., 2009; Mashburn et al., 2008). Coaching teachers in the context of the classroom may be the most effective avenue to improving the intentionality of teachers and supporting children’s development (Mashburn et al., 2008). Ponticell (1995) found that site-based intervention with direct observation and follow-up improved self-analysis of teaching, enabled teachers to learn new ways of collaboratively discussing each other’s teaching, and fostered teachers’ learning and experimenting with new teaching strategies. High-quality professional development is characterized by teachers participating and learning to draw support from peer networks, external professional groups, and site-based professional activities.

Pianta, LaParo and Hamre (2008) recommend that professional development center on specific teacher-child interactions and use standardized, validated measurement. The Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) provides a “common metric, vocabulary, and descriptive base for classroom practices and observations” (La Paro, Pianta, & Stuhlman, 2004, p. 424). The CLASS (Pianta, La Paro, & Hamre, 2008) organizes indicators of teacher-child interactions into 10 dimensions within three broad domains: Emotional Support, Classroom Organization, and Instructional Support.

The CLASS was selected as the pedagogical focus of this coaching project because CLASS dimensions have been shown to significantly predict enhanced social and academic outcomes in prekindergarten (Curby et al., 2009; Howes et al., 2008; Mashburn et al., 2008), kindergarten, and first grade (Hamre & Pianta, 2005).

Coaching

Coaching is an approach to professional development intended to help a teacher transfer new knowledge, strategies, and skills to classroom practice and to promote continuous self-assessment through a cycle of observation, action, and reflection (Rush & Shelden, 2011). To promote substantive changes in teacher beliefs and practices, coaches provide teachers with support that is individualized, collaborative, and frequent (Sheridan, Edwards, Marvin, and Knoche, 2009). Many recent studies report promising results from coaching as an embedded development process (Downer, LoCasale-Crouch, Hamre, & Pianta, 2009; Gallucci, Van Lare, Boatright, & Yoon, 2010; Hsieh, Hemmeter, McCollum, & Ostrosky, 2009; Kissel, Mraz, Algozzine & Stover, 2011; Neuman & Cunningham, 2009).

The Project Approach

Project methods were introduced by Dewey (1916) and made popular by Kilpatrick (1918). In the Project Method, curriculum content was negotiated between teacher and children. The teacher acted as the guide. Teacher and children co-constructed the curriculum, children reconstructed experiences, and interconnections were made between past and future activities (Clark, 2006; Glassman & Whaley, 2000). The Project Method focused on purposive thinking and learning (as opposed to memorizing) and rested upon Dewey’s conception of a “complete act of thought” that proceeds from the effort to solve a problem (Whipple, 1934). Katz and Chard (2000) updated Dewey’s ideas, defining the “Project Approach” as an in-depth investigation of a worthwhile topic and recommending it as one element of any learner-centered curriculum. The Project Approach was selected for this study because long-term investigations help teachers plan opportunities for children to strengthen their intellectual dispositions to take initiative, be curious, pose and solve problems, develop hypotheses, gather data, and revisit and evaluate information (Helm & Katz, 2011).

The research base for the Project Approach is small (Aral, Kandir, Ayhan, & Yasar, 2010; Beneke & Ostrosky, 2009; Dresden & Lee, 2007; Li, 2004), hence the importance of this study of the relationship of the Project Approach and CLASS Instructional Support. Only a few studies have combined the Project Approach and coaching. For instance, Li (2004) combined peer coaching, mentoring, support from an outside consultant, and project work to build a learning community, leading to significant improvements in teaching (Li, 2004, p. 154). In the current study, an outside consultant supported coaches and teachers.

The Role of Teacher Beliefs

There are contrasting belief paradigms about the most effective teaching practices and how children learn best. The National Association for the Education of Young Children’s position statement on developmentally appropriate practices (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009) stresses the importance of child-initiated learning and positive teacher-child relationships. Involving children in curricular decisions and allowing them to share responsibility for their own learning is vital to ensure motivated, lifelong learners.

Child involvement in curricular decisions is central to the Project Approach. However, this can present a challenge for teachers. As Clark (2006) notes, the Project Approach has no scripts, suggested activities, or teacher’s manuals and the role of the teacher can feel uncertain for the novice. Several experiences with projects are necessary before teachers begin to have confidence in the children’s abilities to make significant decisions (Helm & Katz, 2011); as Doyle (1997) notes, changes in teachers’ beliefs may take three to five years. However, the decision was made to use the Teacher Belief Scale (Charlesworth, Hart, Burts, & Hernandez, 1990) in this study to see if pedagogical beliefs would change as teachers learned more about Project Approach practices when supported by weekly coaching in their classrooms. Measurements of teacher beliefs might provide insight into any changes in CLASS scores related to coaching.

Methods

This study described here was part of an ongoing multiyear in-service coaching project. The researchers focused on two questions: (a) Does using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) observational instrument as a professional development tool make a difference in teacher instructional interactions in the classroom? (b) What are the relationships between Head Start teacher ratings in CLASS domains and dimensions, our Project Approach Fidelity form, and pedagogical teacher beliefs scores?

Participants

All participants volunteered for this study. There were 21 Head Start teachers from one Head Start grantee (see Appendix 1 for demographics). Before the study, 11 of the 21 teachers had been exposed to the Project Approach, either through training or classroom practice. At the beginning of the coaching project, teachers participated in a two-hour introduction to CLASS and a two-hour overview of the Project Approach. Each teacher received a CLASS Pre-K Dimensions Guide (Teachstone Training, 2011) and the book Young Investigators: The Project Approach in the Early Years (Helm & Katz, 2011).

Fourteen coaches from the Head Start grantee were involved in the study (see Appendix 1 for coach demographics). Twelve were education coordinators assigned to provide on-site support to teachers, and two were grantee specialists. Prior to the study, the coaches had been trained on coaching roles and processes (Humbarger, 2012). Five of the coaches had attended summer Project Approach institutes. During the study, coaches participated in two days of CLASS training, two training sessions on the Project Approach (including a full-day workshop with Lilian Katz at a local conference), and one training session on the use of video equipment. Coaches received CLASS Pre-K Manuals (Pianta, La Paro, & Hamre, 2008), and the book Young Investigators: The Project Approach in the Early Years (Helm & Katz, 2011).

The role of outside consultant was filled by a colleague from a local university who was part of the coaches’ community of practice and had contributed to the conception of the coaching project. The consultant helped coaches work with teachers as they transferred knowledge and skills into practice. This ongoing support helped build capacity in coaches, many of whom were also learning about CLASS and the Project Approach.

Coaching Procedures

Two professional development concepts informed the development of our coaching processes: inquiry and communities of practice. We selected inquiry as a model for professional development because it provided opportunities for coaches and teachers to engage in a cycle of documentation, analysis, reflection, and action; to focus on children’s learning, particularly the thinking process; to develop positive agency; and to create congruence of practices with coaches, teachers, and children (Catapano, 2005; Helterban & Fennimore, 2004). At the conclusion of the pilot year of this study, the coaches had decided to make explicit an inquiry approach as teacher and coach worked side-by-side, studying videotapes of teacher-child interactions and documentation from the Project Approach to better understand children’s thinking and the effects of specific teaching strategies. The coaches were seeking to create a coaching process that was congruent both in practice and philosophy with the shared inquiry of teacher and children in the Project Approach.

Helm and Katz (2011) note that teachers who have not been able to observe other educators guiding project work “are often at a loss as to how to get a project started and then follow it through. The structure of the project approach, however, provides guidelines for the process” (p. 10). Coaches indicated similar challenges in beginning the inquiry process with teachers. Therefore, five tools were used to provide a framework for analysis of the videos and the documentation to more effectively promote children’s higher level thinking and more accurately assess children’s capabilities:

CLASS Instructional Support domain, which addresses how teachers help students think creatively and solve problems, receive feedback about their learning, and develop more complex language abilities;

The Project Approach as a curriculum element;

The Child Assessment Protocol, which provided opportunities for reflection on specific child documentation related to CLASS and the Project Approach, including language and conversation, writing, drawing, classification, prediction and experimentation;

Analysis of videos of teachers and children thinking together in the classroom;

Coaching Contact Forms, which were used to guide and document the content of the inquiry conducted each week by the coach and teacher and included two questions that supported the development of the community of practice: What are we learning about teaching and learning? How will we share what we learned with others?

This study emerged in the context of a coaches’ community of practice, which we believed would support the complexity of their support for teachers and help build the intellectual and social relationships that would strengthen and advance the work. Our intent was to build a sense of both individual and collective efficacy among the coaches. Coaches met with individual or pairs of teachers for at least one hour each week. Coaches and consultant met monthly as a large group. The consultant also met with individuals or small groups of coaches monthly, or more often if requested. Because the consultant was involved with each of the participants, she was able to advance the work of the community between meetings by sharing effective strategies for teaching and learning that were being developed by coaches and teachers.

Evaluation Procedures

Evaluation instruments used for this study were the CLASS instrument, the Project Approach Fidelity form developed by the authors, and a version of the Teacher Belief Scale.

The CLASS Instrument: Three trained observers used the CLASS instrument to rate Head Start teachers on 10 dimensions of interactions over two-hour observations in the fall and spring. The CLASS (Pianta, La Para, & Hamre, 2008) provides a measure of the quality of three global domains and 10 dimensions of teacher-child interactions in prekindergarten classrooms: 1) Emotional Support domain, which includes the dimensions Positive Climate, Negative Climate, Teacher Sensitivity, and Regard for Student Perspectives; 2) Classroom Organization domain, which includes the dimensions Behavior Management, Productivity, and Instructional Learning Formats; and 3) Instructional Support domain, which includes the dimensions Concept Development, Quality of Feedback, and Language Development. Each CLASS dimension is rated on a 1–7 scale, with 1 or 2 indicating low quality; 3, 4, or 5 indicating mid-quality; and 6 or 7 indicating high quality. The range for each dimension was 1 to 7 and the internal consistency of CLASS (Cronbach’s alpha) was .97 for the fall observations and .96 for the spring observations.

Observers followed the recommended research protocol, wherein each of four 20-minute observations was followed by a 10-minute scoring segment. A teacher score for each dimension was computed and domain scores were tabulated from the dimension scores. (Prior to data collection, inter-rater observer reliability with master codes was determined using videos from Teachstone, the agency that manages the CLASS observational tool. To be reliable all observers were within one scale point of the expert standards or in at least 80% overall agreement with the CLASS training video tapes. During data collection, 10% of the observations were interrated [80% or higher] to ensure reliability of observations.)

Project Approach Fidelity (PAF) Form: To study teachers’ adherence to Project Approach implementation, we developed what we call a Project Approach Fidelity form. The PAF form includes items related to content and instruction as well as teacher/child interaction and is intended to ascertain how closely the teacher adheres to Project Approach practices. The content and instruction items include questions related to the classroom environment, activities, and scheduling (see Appendix 2). The observers completed a PAF form after the CLASS observation of each teacher. Teachers and coaches also completed PAF forms. Cronbach’s alphas for the Project Approach Fidelity form indicated a high degree of internal consistency of the form in both fall .94 (N=22) and spring .95 (N=21). This analysis used only scores from the observer PAF forms, which have been shown to have stronger relationship to observed practice and more appropriate practice than do scores on PAF forms completed by a teacher or a coach (Vartuli & Rohs, 2009).

Teacher Beliefs Scale (TBS). Teachers and coaches completed the Teacher Beliefs Scale (TBS), a survey of teacher beliefs about developmentally appropriate practices ( (Charlesworth et al., 1990) during fall and spring. Items on the TBS represent several areas of instruction specified by the NAEYC guidelines (Bredekamp, 1987): curriculum goals, teaching strategies, guidance, language development and literacy, physical development, aesthetic development, motivation and assessment of children (Charlesworth et al., 1990). The TBS was selected for this study because it addresses specific classroom activities and each activity’s relative importance. A 37-item version of the TBS (Burts et al., 1993; Charlesworth et al., 1990, 1993) was used for this research. The teachers rated each item on a Likert scale from 1 (not important at all) to 5 (extremely important). Cronbach’s alphas were .59 for the fall and .75 for the spring data collections.

Analysis

CLASS domains, dimensions, and indicators were compared with the Project Approach Fidelity items in a crosswalk. (See Appendix 2 for the specific items and dimensions. Note, some of the items on the PAF relate to one or more CLASS domains.) A majority of the PAF items (81%, or 21 out of 26 items) related to the CLASS Instruction Support Domain. Eleven of the 26 PAF items (42%) were similar or equivalent to indicators from the Instructional Learning Formats dimension in the Classroom Organization Domain. Nine out of 26, or 35%, of the PAF items related to the Emotional Support Domain, specifically to the dimensions Teacher Sensitivity and Regard to Student Perspectives.

Correlations of scores from the Teacher Belief Scale (TBS), CLASS, and Project Approach Fidelity (PAF) form were used to explore relationships among/between variables. Linear regressions were used to further explore the relationships between CLASS, teacher beliefs, and Project Approach Fidelity scores. The scores from the TBS, CLASS, and PAF form were normally distributed.

Findings

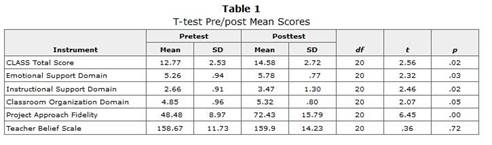

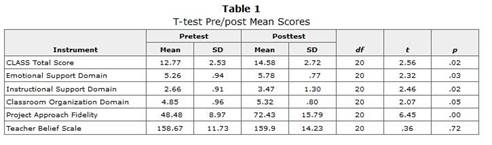

Our first research question was concerned with whether using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) observational instrument as a professional development tool makes a difference in teacher instructional interactions in the classroom. Paired t-tests were computed between fall and spring scores on the 10 dimensions and 3 domains of the CLASS. Paired t-tests of the fall and spring total CLASS scores revealed a meaningful improvement for participants, t = 2.56, 20, p < .02, in demonstrating effective pedagogy. Significant shifts between teacher fall and spring mean scores were found in two domains: Emotional Support t =2.32, 20, p <.03 and Instructional Support t = 2.46, 20, p < .02. Although there was not a significant shift in the Classroom Organization domain t = 2.07, 20, p <.051, the results were positively skewed. The difference in the observer Project Approach Fidelity scores from fall to spring was also significant, t = 6.45, 20, p <.00. (See Table 1 for t-test scores.)

Table 1

The second research question focused on what relationships might exist among Head Start teacher ratings in CLASS domains and dimensions, Project Approach Fidelity, and pedagogical teacher beliefs scores. The observer Project Approach Fidelity (PAF) and teacher belief scores were correlated with the CLASS fall and spring domain scores and CLASS spring total scores. CLASS total scores for spring were significantly correlated with observer PAF scores, r = .76, p < .00 but not with teacher belief scores, r = .28, p < .22 ns also measured in the spring. The PAF appears to have a significant relationship to higher interaction scores as measured by the CLASS within the same time frame. Teacher belief scores appear to be more consistent over time and no significant correlations were found with spring CLASS scores or PAF scores.

Improvement of Project Approach implementation scores was desired because implementation of the Project Approach was a focus of the study. The difference between the observer Project Approach Fidelity fall and spring scores were statistically significantly, t = 6.45, 20, p < .00. The relationship between teacher belief scores and the observer PAF was low moderate, r = .19, (not significant). The lack of statistical significance may be related to the low number of participants or to the gap between belief and practice that researchers have noted in previous studies (McMullen, 1997, 1999; Stipek & Byler, 1997; Vartuli, 1999).

Teacher Belief Scale (TBS) scores and observer Project Approach Fidelity (PAF) scores were used as predictors of scores in the three CLASS domains: Emotional Support, Instructional Support, and Classroom Organization. Linear regression outcomes indicated that the PAF was a significant predictor for CLASS Emotional Support (B = .78, t = 5.70, p < .00), Classroom Organization (B = .65, t = 3.39, p < .03), and Instructional Support domains (B = .69, t = 3.91, p < .00). (See Table 2 for summary scores.)

Table 2

In predicting CLASS scores, Project Approach Fidelity (positive effect) was significant for the Emotional Support, Classroom Organization, and Instructional Support domains. The PAF explained 66% of the variance for the Emotional Support, 43% for the Classroom Organization domain scores, and 46% of the variance on the Instructional Support domain scores. Teacher belief scores were not a significant predictor for any CLASS domains.

Discussion

These findings suggest that an approach to professional development that combines CLASS with the Project Approach enhances teacher-child interactions. It is important to reiterate that all participants were involved in weekly coach/teacher meetings, monthly consultant visits (coach/teacher and consultant), and monthly large group meetings of coaches and consultant. A possible explanation for the gains in scores is that these meetings helped teachers and coaches become more aware of how to implement practices emphasized in CLASS and the Project Approach.

The Project Approach Fidelity scores have a significant positive predictive relationship with all three CLASS domains (Emotional Support, Classroom Organization, and Instructional Support), suggesting that promising gains in teacher-child interactions can be intentionally encouraged through professional development that includes the Project Approach as a curriculum element.

The relationship of the PAF scores to Emotional Support is of particular interest. Hamre and Pianta (2005) found the highest academic achievement in first-grade classrooms with high emotional support, and the Project Approach is noted for the way it encourages children to practice social skills and learn to compromise, negotiate, and resolve conflicts (Helm, 2003; Helm & Lang, 2003; O’Mara Thieman, 2003). The relationship of PAF scores to Instructional Support suggests that the Project Approach promotes higher-level thinking in children and may complement CLASS in encouraging high-quality teacher-child interactions. Pianta (2005) reports that early childhood classrooms tend to be “socially positive but instructionally passive” (p. 239) and proposes that teachers be helped to purposefully challenge and extend children’s learning, especially in light of the finding that the poorest quality teacher profile is associated with poverty-level classrooms (LoCasale-Crouch et al., 2007). In classrooms with teachers who had moderate to high Instructional Support scores, children from a range of backgrounds (high and low maternal education) were found to have similar levels of achievement (Hamre & Pianta, 2005).

Howes et al. (2008) suggest that professional development efforts in Head Start classrooms must improve the quality of interactions because prekindergarten quality predicts future academic performance. Although recent findings have been mixed regarding the relation between child outcomes and higher educator scores on the CLASS Instructional Support Domain (Curby et al., 2009; Domínquez, Vitiello, Maier, & Greenfield, 2010; Guo, Piasta, Justice, & Kaderavek, 2010; Mashburn et al., 2008), we recommend further study of combining the CLASS behaviors with the Project Approach with intentional focus on improving instructional quality and enhancing child outcomes.

In one study, attention to the process of learning and the strategies of teaching was shown to have positive results. Curby et al. (2009) noted that higher CLASS Concept Development and Quality of Feedback scores were related to the greatest academic gains for children. As teachers facilitate project work, they pose problems, engage in feedback loops, ask children to explain their ideas and actions, and promote language use. Children engaged in project work predict, experiment, classify, analyze, reason, plan, and create as they investigate a topic of interest. The teacher-child interactions described by CLASS Concept Development and Quality of Feedback are the same ones teachers use in the Project Approach to further development of children’s intellectual dispositions.

Professional development is critical to increasing teacher knowledge and skills and improving classroom practice (Desimone, 2009; Rudd, Lambert, Satterwhile, & Smith, 2009; Zaslow & Martinez-Beck, 2006) and coaching has been proposed as the key to reforms in teaching and learning. Neuman and Cunningham (2009) have stated that “professional development that contains both content and pedagogical knowledge may best support the ability of teachers to apply knowledge to practice” (p. 534).

The findings of this study also indicate that the curriculum element (the Project Approach) and pedagogy (CLASS Instructional Support domain) were a positive combination for use in coaching focused on improved teacher-child interactions. Although no significant correlations were found between teacher beliefs with CLASS scores, changes in beliefs may be seen later since practice and successful interaction may precede changes in beliefs (Guskey, 1986). Additional coaching may help change teacher beliefs by encouraging reflection that bridges the gap between “espoused theory and actual practice” (Veenman & Denessen, 2001, p. 389).

The small sample size, making this an exploratory study, is one of its limitations. Also, as with most research into coaching, there is natural variation in how coaching support was given to teachers and how teachers engaged with and responded to the treatment. Finally, child outcomes are not included. In future research, the number of coaches and teachers will be expanded. Measures of coaching interaction variations will be included. Child outcome data will also be included to determine if higher teacher scores on CLASS and Project Approach Fidelity correlate with enhancement of children’s learning.

Conclusion

This study focused on improvement of teacher-child interactions as described in the CLASS Instructional Support domain. Expectations were clear regarding the frequency, intensity, and duration of coaching sessions. The tools provided to coaches and teachers were carefully selected and philosophically aligned. Significant shifts in CLASS ratings resulted. Implementation of the Project Approach as a curriculum element predicted higher CLASS scores, suggesting that the coaching was enhanced when teacher-child interactions were more closely connected to classroom curriculum.

The addition of the Project Approach as a curriculum element created a congruence between teaching and coaching practices. Teachers and children investigated interesting and worthwhile topics together. Teachers and coaches researched instructional practices and interactions in an effort to promote children’s higher-order thinking. The coaches and consultant strengthened our community of practice by inquiring together into effective strategies for supporting professional development.

References

1-

Aral, Neriman; Kandir, Adalet; Ayhan, Aynur B.; & Yaşar, Münevver C. (2010). The influence of project-based curricula on six-year-old preschoolers’ conceptual development. Social Behavior and Personality, 38, 1073–1080. doi:10.2224/sbp.2010.38.8.1073

2-

Beneke, Sallee, & Ostrosky, Michaelene M. (2009). Teachers’ views of the efficacy of incorporating the Project Approach into classroom practice with diverse learners. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 11(1). English | Spanish

3-

Bogard, Kimber; Traylor, Fasaha; & Takanishi, Ruby. (2008). Teacher education and PK outcomes: Are we asking the right questions? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.08.002

4-

Bredekamp, Sue (Ed.). (1987). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8. Washington, D.C.: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

5-

Burts, Diane C.; Hart, Craig H.; Charlesworth, Rosalind; DeWolf, D. Michele; Ray, Jeanette; Manuel, Karen; & Fleege, Pamela O. (1993). Developmental appropriateness of kindergarten programs and academic outcomes in first grade. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 8, 23–31. doi:10.1080/02568549309594852

6-

Catapano, Susan. (2005). Teacher professional development through children’s project work. Early Childhood Education Journal, 32, 261–267. doi:10.1007/s10643-004-1428-2

7-

Charlesworth, Rosalind; Hart, Craig H.; Burts, Diane C.; & Hernandez, Sue. (1990). Kindergarten teachers’ beliefs and practices. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Boston.

8-

Charlesworth, Rosalind; Hart, Craig H.; Burts, Diane C.; Thomasson, Renee H.; Mosley, Jean; & Fleege, Pamela O. (1993). Measuring the developmental appropriateness of kindergarten teachers’ beliefs and practices. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 8, 255–276. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(05)80067-5

9-

Chien, Nina C.; Howes, Carollee; Burchinal, Margaret; Pianta, Robert C.; Ritchie, Sharon; Bryant, Donna M.; … Barbarin, Oscar A. (2010). Children’s classroom engagement and school readiness gains in prekindergarten. Child Development, 81, 1534–1549. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01490.x

10-

Clark, Ann-Marie. (2006). Changing classroom practice to include the Project Approach. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 8(2). English | Spanish

11-

Copple, Carol, & Bredekamp, Sue (Eds.). (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8 (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

12-

Curby, Timothy W.; LoCasale-Crouch, Jennifer; Konold, Timothy R.; Pianta, Robert C.; Howes, Carollee; Burchinal, Margaret; … Barbarin, Oscar. (2009). The relations of observed pre-k classroom quality profiles to children’s achievement and social competence. Early Education and Development, 20, 346–372. doi:10.1080/10409280802581284

13-

Desimone, Laura M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38, 181–199. doi:10.3102/0013189X08331140

14-

Dewey, John. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: Macmillan.

15-

Domínguez, Ximena; Vitiello, Virginia E.; Maier, Michelle F., & Greenfield, Daryl B. (2010). A longitudinal examination of young children’s learning behavior: Child-level and classroom-level predictors of change throughout the preschool year. School Psychology Review, 39, 29–47.

16-

Downer, Jason T.; LoCasale-Crouch, Jennifer; Hamre, Bridget; & Pianta, Robert. (2009). Teacher characteristics associated with responsiveness and exposure to consultation and online professional development resources. Early Education and Development, 20, 431–455. doi:10.1080/10409280802688626

17-

Downer, Jason; Pianta, Robert; Fan, Xitao; Hamre, Bridget; Mashburn, Andrew; & Justice, Laura. (2011). Effects of web-mediated teacher professional development on the language and literacy skills of children enrolled in prekindergarten programs. NHSA Dialog, 14(4), 189–212. doi:10.1080/15240754.2011.613129

18-

Doyle, Marie. (1997). Beyond life history as a student: Preservice teachers’ beliefs about teaching and learning. College Student Journal, 31, 519–531.

19-

Dresden, Janna, & Lee, Kyunghwa. (2007). The effects of project work in a first-grade classroom: A little goes a long way. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 9(1). English | Spanish

20-

Gallucci, Chrysan; Van Lare, Michelle DeVoogt; Yoon, Irene H; & Boatright, Beth. (2010). Instructional coaching: Building theory about the role and organizational support for professional learning. American Educational Research Journal, 47, 919–963. doi:10.3102/0002831210371497

21-

Glassman, Michael, & Whaley, Kimberlee. (2000). Dynamic aims: The use of long-term projects in early childhood classrooms in light of Dewey’s education philosophy. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 2(1).

22-

Guskey, Thomas R. (1986). Staff development and the process of teacher change. Educational Researcher, 15(5), 5–12. doi:10.3102/0013189X015005005

23-

Guo, Ying; Piasta, Shayne B.; Justice, Laura M.; & Kaderavek, Joan N. (2010). Relations among preschool teachers’ self-efficacy, classroom quality, and children’s language and literacy gains. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 1094–1103. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.11.005

24-

Hamre, Bridget. K., & Pianta, Robert C. (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development, 76, 949–967. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00889.x

25-

Helm, Judy Harris. (2003). Overcoming the ill effects of poverty: Defining the challenge. In Judy Harris Helm & Sallee Beneke (Eds.), The power of projects: Meeting contemporary challenges in early childhood classrooms–strategies and solutions (pp. 34). New York: Teachers College Press.

26-

Helm, Judy Harris, & Katz, Lilian. (2011). Young investigators: The Project Approach in the early years (2nd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press.

27-

Helm, Judy Harris, & Lang, Jean. (2003). Overcoming the ill effects of poverty: Practical strategies. In Judy Harris Helm & Sallee Beneke (Eds.), The power of projects: Meeting contemporary challenges in early childhood classrooms–strategies and solutions (pp. 35–41). New York: Teachers College Press.

28-

Helterbran, Valeri R., & Fennimore, Beatrice S. (2004). Collaborative early childhood professional development: Building from a base of teachers’ investigation. Early Childhood Education Journal, 31, 267–271. doi:10.1023/B:ECEJ.0000024118.99085.ff

29-

Howes, Carollee; Burchinal, Margaret; Pianta, Robert; Bryant, Donna; Early, Diane; Clifford, Richard; & Barbarin, Oscar. (2008). Ready to learn? Children’s pre-academic achievement in pre-kindergarten programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 27–50. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.05.002

30-

Hsieh, Wu-Ying; Hemmeter, Mary L.; McCollum, Jeanette A., & Ostrosky, Michaelene M. (2009). Using coaching to increase preschool teachers’ use of emergent literacy teaching strategies. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24, 229–247. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.03.007

31-

Humbarger, Joy A. (2012). Strengths-based coaching & facilitator guide [Registered curriculum]. Francis Institute for Child and Youth Development, the Community College District of Metropolitan Kansas City, MO.

32-

Katz, Lilian G., & Chard, Sylvia C. (2000). Engaging children’s minds: The project approach. Stamford, CT: Ablex.

33-

Kilpatrick, William. (1918). The project method. Teachers College Record, 19, 319–335..

34-

Kissel, Brian; Mraz, Maryann; Algozzine, Bob; & Stover, Katie. (2011). Early childhood literacy coaches’ role perceptions and recommendations for change. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 25, 288–303. doi:10.1080/02568543.2011.580207

35-

La Paro, Karen M.; Pianta, Robert C.; & Stuhlman, Megan. (2004). The classroom assessment scoring system (CLASS): Findings from the prekindergarten year. Elementary School Journal, 104, 409–426.

36-

Li, Yuen L. (2004). A school-based project in five kindergartens: The case of teacher development and school development. International Journal of Early Years Education, 12, 143–155. doi:10.1080/0966976042000225534

37-

Lieber, Joan; Butera, Gretchen; Hanson, Marci; Palmer, Susan; Horn, Eva; Czaja, Carol; … Odom, Samuel. (2009). Factors that influence the implementation of a new preschool curriculum: Implications for professional development. Early Education and Development, 20, 456–481. doi:10.1080/10409280802506166

38-

LoCasale-Crouch, Jennifer; Konold, Tim; Pianta, Robert; Howes, Carollee; Burchinal, Margaret; Bryant, Donna; … Barbarin, Oscar. (2007). Observed classroom quality profiles in state-funded pre-kindergarten programs and associations with teacher, program and classroom characteristics. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22, 3–17. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.05.001

39-

Mashburn, Andrew J.; Pianta, Robert C.; Hamre, Bridget K.; Downer, Jason T.; Barbarin, Oscar A.; Bryant, Donna; … Howes, Carollee. (2008). Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children’s development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Development, 79, 732–749. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01154.x

40-

McMullen, Mary Benson. (1997). The effects of early childhood academic and professional experience on self-perceptions and beliefs about developmentally appropriate practices. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 18(3), 55–68. doi:10.1080/1090102970180307

41-

McMullen, Mary Benson. (1999). Characteristics of teachers who talk the DAP talk and walk the DAP walk. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 13, 216–230. doi:10.1080/02568549909594742

42-

Neuman, Susan B., & Cunningham, Linda. (2009). The impact of professional development and coaching on early language and literacy instructional practices. American Educational Research Journal, 46, 532–566. doi:10.3102/0002831208328088

43-

O’Mara Thieman, Jean. (2003). The water to river project. In Judy Harris Helm & Sallee Beneke (Eds.), The power of projects: Meeting contemporary challenges in early childhood classrooms–strategies and solutions (pp. 42–49). New York: Teachers College Press.

44-

Pianta, Robert C. (2005). Standardized observation and professional development: A focus on individualized implementation and practices. In Martha Zaslow & Ivelisse Marinez-Beck (Eds), Critical issues in early childhood professional development (pp. 231–254). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

45-

Pianta, Robert C. (2006, August). Standardized classroom observations from pre-K to 3rd grade: A mechanism for improving access to consistently high quality classroom experiences and practices during the P-3 years (Discussion Paper 103).Minneapolis, MN: Early Childhood Research Collaborative.

46-

Pianta, Robert; Howes, Carollee; Burchinal, Margaret; Byrant, Donna; Clifford, Richard; Early, Diane; & Barbarin, Oscar. (2005). Features of pre-kindergarten programs, classrooms, and teachers: Do they predict observed classroom quality and child-teacher interactions? Applied Developmental Science, 9, 144–159. doi:10.1207/s1532480xads0903_2

47-

Pianta, Robert C.; LaParo, Karen M.; & Hamre, Bridget K. (2008). Classroom assessment scoring system manual pre-k. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

48-

Pianta, Robert C., Mashburn, Andrew J.; Downer, Jason T.; Hamre, Bridget K.; & Justice, Laura. (2008). Effects of web-mediated professional development resources on teacher-child interactions in pre-kindergarten classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 431–451. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.02.001

49-

Ponticell, Judith A. (1995). Promoting teacher professionalism through collegiality. Journal of Staff Development, 16(3), 13–18.

50-

Rudd, Loretta C.; Lambert, Matthew C.; Satterwhite, Macy; & Smith, Cinda H. (2009). Professional development + coaching = enhanced teaching: Increasing usage of math mediated language in preschool classrooms. Early Childhood Education Journal, 37, 63–69. doi:10.1007/s10643-009-0320-5

51-

Rush, Dathan D., & Shelden, M’Lisa L. (2011). The early childhood coaching handbook. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

52-

Sheridan, Susan M.; Edwards, Carolyn Pope; Marvin, Christine A., & Knoche, Lisa L. (2009). Professional development in early childhood programs: Process issues and research needs. Early Education and Development, 20, 377–401. doi:10.1080/10409280802582795

53-

Stipek, Deborah J., & Byler, Patricia. (1997). Early childhood education teachers: Do they practice what they preach? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 12, 305–325. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(97)90005-3

54-

Teachstone Training. (2011). Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) Dimensions Guide, Pre-K. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

55-

Whipple, Guy Montrose (Ed.). (1934). The thirty-third yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, Part II: The activity movement. Bloomington, IL: Public School.

56-

Vartuli, Sue. (1999). How early childhood beliefs vary across grade level. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 14, 489–514. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(99)00026-5

57-

Vartuli, Sue, & Rohs, Jovanna (2009). Assurance of outcome evaluation: Curriculum fidelity. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 23, 502–512. doi:10.1080/02568540909594677

58-

Veenman, Simon, & Denessen, Eddie. (2001). The coaching of teachers: Results of five training studies. Educational Research and Evaluation, 7, 385–417. doi:10.1076/edre.7.4.385.8936

59-

Zaslow, Martha, & Martinez-Beck, Ivelisse. (Eds.). (2005). Critical issues in early childhood professional development. Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks.

Author Information

Sue Vartuli was the evaluator for the Coaching Project at Mid-America Head Start. She received her master’s and doctorate from The Ohio State University. Until her retirement, she was associate professor of early childhood education at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, where she was a teacher educator for 33 years. Her research is focused on teacher education, especially teacher beliefs, guidance, and curriculum.

Sue Vartuli

10141 Edelweiss Circle

Merriam, Kansas 66203

Carol Bolz was the coordinator for the Coaching Project. She is the education specialist for Mid-America Head Start and has served as a classroom teacher, education coordinator, and center director. She has a master’s in curriculum and instruction with early childhood emphasis from the University of Missouri–Kansas City.

Catherine Wilson was the consultant for the Coaching Project at Mid-America Head Start. She holds an M.L.S. from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, a master’s in early childhood education, and Ph.D. in curriculum and instruction from the University of Missouri–Kansas City. Before retirement, she was associate professor of early childhood education at Park University. She is the author of Telling a Different Story: Teaching and Literacy in an Urban Preschool and co-author with Stacie G. Goffin of Curriculum Models and Early Childhood Education: Appraising the Relationship (2nd edition).

16%

16%

Author: www.ecrp.uiuc.edu

Author: www.ecrp.uiuc.edu