Marriage and Home

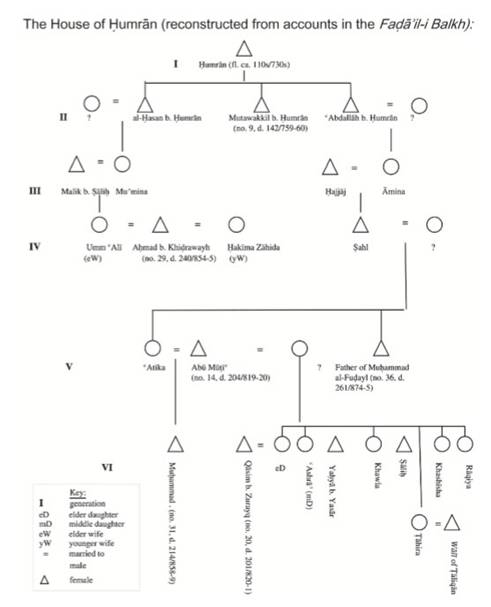

Nowhere have I found Umm ʿAlī’s birth or death dates. The lack of dates is a common feature in mediaeval accounts on Muslim learned women in general. Fortunately, the biography of her husband Aḥmad b. Khiḍrawayh in the Faḍāʾil-i Balkh gives some information that allows us to home in on the second half of the ninth century. The clue is that, when Umm ʿAlī returned to Balkh from Mecca, her husband had already died. We know from the Faḍāʾil-i Balkh and other sources that Aḥmad died in 240/854-5, at the age of ninety-five. This sets the terminus post quem for Umm ʿAlī’s death at 240/854-5. If she did survive to old age, she would probably have lived well into the second half of the ninth century CE.

The Faḍāʾil-i Balkh does not mention Umm ʿAlī’s given name, but other sources do. Al-Hujwīrī tells us in his Kashf al-maḥjūb that Umm ʿAlī’s name was Fātịma.

Umm ʿAlī married well, as one might expect for a woman of her standing (see below), but she did not marry a wealthy noble, choosing instead one of Balkh’s most beloved scholars and mystics, the qāḍī Abū Ḥāmid Aḥmad b. Khiḍrawayh (d. 240/854-5), who receives ample treatment in the Faḍāʾil-i Balkh

and other hagiographical sources and is known as an example of the futuwwa (spiritual chivalry).

Gramlich does not see him as a proponent of the malāmatiyya –the early Islamic mystical tradition that originated in Khorasan and based itself on the tenet that all outward appearance of piety or religiosity is ostentation– but, as Hamid Algar explains, the concepts of futuwwa and the malāma overlap during this period.

As a fatā (a young male exponent of futuwwa), Aḥmad is credited with exhibiting much generosity, which left him in a constant state of debt.

He expounded on the mystical concepts of seeking refuge in God alone, outlined a ten-step process to attain the Sufi ṭarīqa, and pondered the battle with the soul (nafs). He is said to have met and studied with major shuyūkh, such as Ibrāhīm b. Adham (d. 161/777-8), Ḥātim al-Asạ mm (d. 237/857-8), and Abū Ḥ afs ̣ b. Ḥ addād (d. c. 265/878-9) in Nishapur. Much is also written about his stay with Abū Yazīd al-Bistạ̄ mī (d. 261/874-5?).

Aḥmad b. Khiḍrawayh had many students, including some better-known authorities.

According to ʿAbdallāh al-Ansạ̄ rī al-Harawī (d. 481/1089), who mentions Umm ʿAlī only in passing, Aḥmad b. Khiḍrawayh also performed the ḥajj to Mecca, besides visiting the above-mentioned masters.

While one might assume that Shaykh Aḥmad had chosen his betrothed, al-Hujwīrī’s account and those of his successors tell us that it was quite the opposite: Umm ʿAlī wooed Aḥmad. Umm ʿAlī’s decision to marry apparently came after a change of heart on the matter. We are not told what made her change her mind, but perhaps the message here is to stress the importance of marriage even for pious, mystical women. Al-Hujwīrī states that Umm ʿAlī had to ask Aḥmad more than once before he complied, and then only after she had cunningly appealed to his spiritual conscience.

Al-Hujwīrī says:

Chūn way-rā irādat-i tawba padīdār āmad, bi Aḥmad kas firistād, ki: “Ma-rā az pidar bikhwāh.” Way ijābat nakard. Kas firistād, ki: “Yā Aḥmad, man tū-rā mard-i ān napindāshtam ki rāh-i ḥaqq nazanī. Rāh-bar bāsh na rāh-bur.” Aḥmad kas firistād, wa way-rā as pidar bikhwāst.

When she changed her mind, she sent someone [with a message] to Aḥmad: “Ask my father for my hand.” He did not respond. She sent someone [again with a message]: “Oh Aḥmad, I did not think you a man who would not follow the path of truth. Be a guide of the road; do not put obstacles on it.” Aḥmad sent someone [with a message] to ask her father for her hand.

In Atṭ ạ̄ r’s Tadhkirat al-awliyāʾ, Shaykh Aḥmad’s biographical entry contains a discussion of his wife Fātịma as a miracle-working mystic and “an accomplished master of the Sufi path” (andar ṭarīqat, āyat-ī būd).

From here on, Atṭ ạ̄ r’s account closely resembles that of al-Hujwīrī. The latter recounts her wooing of Aḥmad thus:

Tawbat kard wa bar Aḥmad kas firistād, ki: “Ma-rā az pidar bikhwāh.” Aḥmad ijābat nakard. Dīgar bār kas firistād, ki: “Ay Aḥmad, man tu-rā mardāna-tar az īn dānistam. Rāh-bar bāsh, na rāh-bur.” Aḥmad kas firistād wa az pidar bikhwāst.

She changed her mind, and sent someone to Aḥmad [with the message:] “Ask my father for my hand.” Aḥmad did not respond. Once more, she sent someone [with the message:] “Oh Aḥmad, I thought you were more manly than this. Be a guide of the road; do not put obstacles on it.” Aḥmad sent [a messenger] and asked her father for her hand.

Al-Hujwīrī, too, identified Umm ʿAlī as the daughter of a high official, although he calls her “daughter of the amīr of Balkh.”

The imprecision about Fātịma’s lineage - she was the granddaughter of Balkh’s governor, as will be seen shortly - is repeated in later sources of the same genre. It contrasts with the persistence of the image of Umm ʿAlī as astute and “manly.”

After all, convention would have it that the man proposes to his prospective wife, and not vice versa.

0%

0%

Author: Arezou Azad

Author: Arezou Azad