Chapter 3: Ghadir Khumm and the Orientalists

1. Introduction

The 18th of Dhu 'l-Hijja is celebrated in the Shí'a world as the 'idd of Ghadir Khumm in which Prophet Muhammad (s.a.w.) said about Imam 'Ali: "Whomsoever's master (mawla) I am, this 'Ali is also his master." This event is of such significance to the Shí'as that no serious scholar of Islam can ignore it. The purpose of this paper is to study how the Orientalists handled the event of Ghadir Khumm. By "orientalists", I mean the Western scholarship of Islam and also those Easterners who received their entire Islamic training under such scholars.

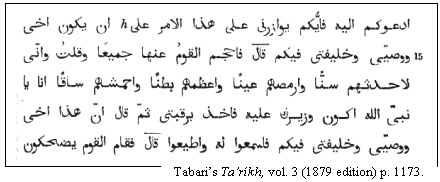

Before proceeding further, a brief narration of the event of Ghadir Khumm would not be out of place. This will be especially helpful to those who are not familiar with the event. While returning from his last pilgrimage, the Prophet received the following command of Allãh: "O the Messenger! Convey what had been revealed to you from your Lord; if you do not do so, then [it would be as if] you have not conveyed His message [at all]. Allãh will protect you from the people." (The Qur'ãn 5:67) Therefore he stopped at Ghadir Khumm on the 18th of Dhu 'l-Hijja, 10 AH to convey the message to the pilgrims before they dispersed. At one point, he asked his followers whether he, Muhammad, had more authority (awla) over the believers than they had over themselves; the crowd cried out, "Yes, it is so, O Apostle of Allãh." Then he took 'Ali by the hand and declared: "Whomsoever's master (mawla) I am, this 'Ali is also his master - man kuntu mawlahu fa hadha 'Aliyun mawlahu." Then the Prophet also announced his impending death and charged the believers to remain attached to the Qur'ãn and to his Ahlul Bayt. This summarizes the important parts of the event of Ghadir Khumm.

The main body of this paper is divided as follows: Part II is a brief survey of the approach used by the Orientalists in studying Shí'ism. Part III deals with the approach used to study Ghadir Khumm in particular. Part IV is a critical review of what M.A. Shaban has written about the event in his Islamic History AD 600-750. This will be followed by a conclusion.

2. Study of Shí'ism by the Orientalists

When the Egyptian writer, Muhammad Qutb, named his book as Islam: the Misunderstood Religion, he was politely expressing the Muslim sentiment about the way Orientalists have treated Islam and Muslims in general. The word "misunderstood" implies that at least a genuine attempt was made to understand Islam. However, a more blunt criticism of Orientalism, shared by the majority of Muslims, comes from Edward Said, "The hardest thing to get most academic experts on Islam to admit is that what they say and do as scholars is set in a profoundly and in some ways an offensively political context. Everything about the study of Islam in the contemporary West is saturated with political importance, but hardly any writers on Islam, whether expert or general, admit the fact in what they say. Objectivity is assumed to inhere in learned discourse about other societies, despite the long history of political, moral, and religious concern felt in all societies, Western or Islamic, about the alien, the strange and different. In Europe, for example, the Orientalist has traditionally been affiliated directly with colonial offices."

Instead of assuming that objectivity is inhere in learned discourse, Western scholarship has to realize that precommitment to a political or religious tradition, on a conscious or subconscious level, can lead to biased judgement. As Marshall Hudgson writes, "Bias comes especially in the questions he poses and in the type of category he uses, where indeed, bias is especially hard to track down because it is hard to suspect the very terms one uses, which seem so innocently neutral..."

The Muslim reaction to the image portrayed of them by Western scholarship is beginning to get its due attention. In 1979, the highly respected scholar trained in Western academia, Albert Hourani, said, "The voices of those from the Middle East and North Africa telling us that they do not recognize themselves in the image we have formed of them are too numerous and insistent to be explained in terms of academic rivalry or national pride."

This was about Islam and Muslims vis-à-vis the Orientalists.

When we focus on the study of Shí'ism by the Orientalists, the word "misunderstood" is not strong enough; rather it is an understatement. Not only is Shí'ism misunderstood, it has been ignored, misrepresented and studied mostly through the heresiographic literature of their opponents. It seems as if the Shí'ites had no scholars and literature of their own. To borrow an expression from Marx, "they cannot represent themselves, they must be represented," and that also by their adversaries!

The reason for this state of affairs lies in the paths through which Western scholars entered the field of Islamic studies. Hodgson, in his excellent review of Western scholarship, writes, "First, there were those who studied the Ottoman Empire, which played so major a role in modern Europe. They came to it usually in the first instance from the viewpoint of the European diplomatic history. Such scholars tended to see the whole of Islamdom from the political perspective of Istanbul, the Ottoman capital. Second, there were those, normally British, who entered Islamic studies in India so as to master Persian as good civil servants, or at least they were inspired by Indian interest. For them, the imperial transition of Delhi tended to be the culmination of Islamicate history. Third, there were the Semitists, often interested primarily in Hebrew studies, who were lured into Arabic. For them, headquarters tended to be Cairo, the most vital of Arabic-using cities in the nineteenth century, though some turned to Syria or the Maghrib. They were commonly philologians rather than historians, and they learned to see Islamicate culture through the eyes of the late Egyptian and Syrian Sunni writers most in vogue in Cairo. Other paths-that of the Spaniards and some Frenchmen who focused on the Muslims in Medieval Spain, that of the Russians who focused on the northern Muslims-were generally less important."

It is quite obvious that none of these paths would have led Western scholars to the centres of Shí'a learning or literature. The majority of what they studied about Shí'ism was channelled through the non-Shí'i sources. Hudgson, who deserves our highest praise for noticing this point, says, "All paths were at one in paying relatively little attention to the central areas of the Fertile Crescent and Iran, with their tendency towards Shí'ism; areas that tended to be most remote from western penetration."

And after the First World War, "the Cairene path to Islamic studies became the Islamicist's path par excellence, while other paths to Islamic studies came to be looked on as of more local relevance."

Therefore, whenever an Orientalist stuided Shí'ism through Ottoman, Cairene or Indian paths, it was quite natural for him to be biased against Shí'a Islam. "The Muslim historians of doctrine [who are mostly Sunni] always tried to show that all other schools of thought other than their own were not only false but, if possible, less than truly Muslim. Their work described innumerable 'firqahs' in terms which readily misled modern scholars into supposing they were referring to so many 'heretical sects'."

And so we see that until very recently, Western scholars easily described Sunni'ism as 'orthodox Islam' and Shí'ism as a 'heretical sect'. After categorizing Shí'ism as a heretical sect of Islam, it became "innocently neutral" for Western scholars to absorb the Sunni scepticism concerning the early Shí'a literature. Even the concept of taqiyyah (dissimulation when one's life is in danger) was blown out of proportion and it was assumed that every statement of a Shí'a scholar had a hidden meaning. And, consequently, whenever an Orientalist studied Shí'ism, his precommitment to Judeo-Christian tradition of the West was compounded with the Sunni bias against Shí'ism.

One of the best examples of this compounded bias is found in the way the event of Ghadir Khumm was studied by the Orientalists, an issue that forms the main purpose of this paper.

3. Ghadír Khumm: From Oblivion to Recognition

The event of Ghadir Khumm is a very good example to trace the Sunni bias that found its way into the mental state of Orientalists. Those who are well-versed with the polemic writings of Sunnis know that whenever the Shí'as present a hadíth or a historical evidence in support of their view, a Sunni polemicist would respond in the following manner:

Firstly, he will outright deny the existence of any such hadíth or historical event.

Secondly, when confronted with hard evidence from his own sources, he will cast doubt on the reliability of the transmitters of that hadíth or event.

Thirdly, when he is shown that all the transmitters are reliable by Sunni standards, he will give an interpretation to the hadíth or the event that will be quite different from that of the Shí'as.

These three levels form the classical response of the Sunni polemicists in dealing with the arguments of the Shí'as. A quotation from Rosenthal's translation of Ibn Khaldun's The Muqaddimah would suffice to prove my point. (Ibn Khaldun is quoting the following part from al-Milal wa 'n-Nihal, a heresiographic work of ash-Shahristãni.) According to Ibn Khaldun, the Shí'as believe that

'Ali is the one whom Muhammad appointed. The (Shí'ah) transmit texts (of traditions) in support of (this belief)...The authority on the Sunnah and the transmitters of the religious law do not know these texts.

Most of them are supposititious, or

some of their transmitters are suspect, or

their (true) interpretation is very different from the wicked interpretation that (the Shí'ah) give to them.

Interestingly, the event of Ghadir Khumm has suffered the same fate at the hands of Orientalists. With the limited time and resources available to me at this moment, I was surprised to see that most works on Islam have ignored the event of Ghadir Khumm, indicating, by its very absence, that the Orientalists believed this event to be 'supposititious' and an invention of the Shí'as. Margoliouth's Muhammad and the Rise of Islam (1905), Brockelmann's History of the Islamic People (1939), Arnold and Guillaume's The Legacy of Islam (1931), Guillaume's Islam (1954), von Grunebaum's Classical Islam (1963), Arnold's The Caliphate (1965), and The Cambridge History of Islam (1970) have completely ignored the event of Ghadir Khumm.

Why did these and many other Western scholars ignore the event of Ghadir Khumm? Since Western scholars mostly relied on anti-Shí'a works, they naturally ignored the event of Ghadir Khumm. L. Veccia Vaglieri, one of the contributors to the second edition of the Encyclopaedia of Islam (1953), writes:

Most of those sources which form the basis of our knowledge of the life of Prophet (Ibn Hishãm, al-Tabari, Ibn Sa'd, etc.) pass in silence over Muhammad's stop at Ghadir Khumm, or, if they mention it, say nothing of his discourse (the writers evidently feared to attract the hostility of the Sunnis, who were in power, by providing material for the polemic of the Shí'is who used these words to support their thesis of 'Ali's right to the caliphate). Consequently, the western biographers of Muhammad, whose work is based on these sources, equally make no reference to what happened at Ghadir Khumm.

Then we come to those few Western scholars who mention the hadíth or the event of Ghadir Khumm but express their scepticism about its authority-the second stage in the classical response of the Sunni polemicists.

The first example of such scholars is Ignaz Goldziher, a highly respected German Orientalist of the nineteenth century. He discusses the hadíth of Ghadir Khumm in his Muhammedanische Studien (1889-1890) translated into English as Muslim Studies (1966-1971) under the chapter entitled as "The Hadíth in its Relation to the Conflicts of the Parties of Islam." Coming to the Shí'as, Goldziher writes:

A stronger argument in their [Shí'as'] favour...was their conviction that the Prophet had expressly designated and appointed 'Ali as his successor before his death...Therefore the 'Alid adherents were concerned with inventing and authorizing traditions which prove 'Ali's installation by direct order of the Prophet. The most widely known tradition (the authority of which is not denied even by orthodox authorities though they deprive it of its intention by a different interpretation) is the tradition of Khumm, which came into being for this purpose and is one of the firmest foundation of the theses of the 'Alid party.

One would expect such a renowned scholar to prove how the Shí'as "were concerned with inventing" traditions to support their theses, but nowhere does Goldziher provide any evidence. After citing at-Tirmidhi and al-Nasã'i in the footnote as the source for hadíth of Ghadir Khumm, he says, "Al-Nasã'i had, as is well known, pro-'Alid inclinations, and also at-Tirmidhi included in his collection tendentious traditions favouring 'Ali, e.g., the tayr tradition."

This is again the same old classical response of the Sunni polemicists-discredit the transmitters as unreliable or adamantly accuse the Shí'as of inventing the traditions.

Another example is the first edition of the Encyclopaedia of Islam (1911-1938) which has a short entry under "Ghadir Khumm" by F. Bhul, a Danish Orientalist who wrote a biography of the Prophet. Bhul writes, "The place has become famous through a tradition which had its origin among the Shi'is but is also found among Sunnis, viz., the Prophet on journey back from Hudaibiya (according to others from the farewell pilgrimage) here said of 'Ali: Whomsoever I am lord of, his lord is 'Ali also!"

Bhul makes sure to emphasize that the hadíth of Ghadir has "its origin among the Shí'is!"

Another striking example of the Orientalists' ignorance about Shí'ism is A Dictionary of Islam (1965) by Thomas Hughes. Under the entry of Ghadir, he writes, "A festival of the Shi'ahs on the 18th of the month of Zu 'l-Hijjah, when three images of dough filled with honey are made to represent Abu Bakr, 'Umar, and 'Uthmãn, which are struck with knives, and the honey is sipped as typical of the blood of the usurping Khalifahs. The festival is named for Ghadir, 'a pool,' and the festival commemorates, it is said, Muhammad having declared 'Ali his successor at Ghadir Khum, a watering place midway between Makkah and al-Madinah."

Coming from a Shí'a family that traces its ancestory back to the Prophet himself, having studied in Iran for ten years and lived among the Shí'as of Africa and North America, I have yet to see, hear or read about the dough and honey ritual of Ghadir! I was more surprised to see that even Vaglieri, in the second edition of the Encyclopaedia, has incorporated that nonsense into her fairly excellent article on Ghadir Khumm. She adds at the end that, "This feast also holds an important place among the Nusayris." It is quite possible that the dough and honey ritual is observed by the Nusayris; it has nothing to do with the Shí'as. But do all Orientalists know the difference between the Shí'as and the Nusayris? I very much doubt so.

A fourth example from the contemporary scholars who have treaded the same path is Philip Hitti in his History of the Arabs (1964). After mentioning that the Buyids established "the rejoicing on that [day] of the Prophet's alleged appointment of 'Ali as his successor at Ghadir Khumm," he describes the location of Ghadir Khumm in the footnote as "a spring between Makkah and al-Madinah where Shí'ite tradition asserts the Prophet declared, 'Whomsoever I am lord of, his lord is 'Ali also'."

Although this scholar mentions the issue of Ghadir in a passing manner, he classifies the hadíth of Ghadir is a "Shí'ite tradition".

To these scholars who, consciously or unconsciously, have absorbed the Sunni bias against Shí'ism and insist on the Shí'ite origin or invention of the hadíth of Ghadir, I would just repeat what Vaglieri has said in the Encyclopaedia of Islam about Ghadir Khumm:

It is, however, certain that Muhammad did speak in this place and utter the famous sentence, for the account of this event has been preserved, either in a concise form or in detail, not only by al-Ya'kubi, whose sympathy for the 'Alid cause is well known, but also in the collection of traditions which are considered canonical, especially in the Musnad of Ibn Hanbal; and the hadiths are so numerous and so well attested by the different isnãds that it does not seem possible to reject them.

Vaglieri continues, "Several of these hadiths are cited in the bibliography, but it does not include the hadíth which, although reporting the sentence, omit to name Ghadir Khumm, or those which state that the sentence was pronounced at al-Hudaybiya. The complete documentation will be facilitated when the Concordance of Wensinck have been completely published. In order to have an idea of how numerous these hadiths are, it is enough to glance at the pages in which Ibn Kathir has collected a great number of them with their isnads."

It is time the Western scholarship made itself familiar with the Shí'ite literature of the early days as well as of the contemporary period. The Shí'a scholars have produced great works on the issue of Ghadir Khumm. Here I will just mention two of those:

1. The first is 'Abaqãtu 'l-Anwãr in eleven bulky volumes written in Persian by Mir Hãmid Husayn al-Musawi (d. 1306 AH) of India. 'Allãmah Mir Hãmid Husayn has devoted three bulky volumes (consisting of about 1080 pages) on the isnãd, tawãtur and meaning of the hadíth of Ghadir. An abridged version of this work in Arabic translation entitled as Nafahãtu 'l-Azhãr fi Khulãsati 'Abaqãti 'l-Anwãr by Sayyid 'Ali al-Milãni has been published in twelve volumes by now; and four volumes of these (with modern type-setting and printing) are dedicated to the hadíth of Ghadír.

2. The second work is al-Ghadír in eleven volumes in Arabic by 'Abdul Husayn Ahmad al-Amini (d. 1970) of Iraq. 'Allãmah Amini has given with full references the names of 110 companions of the Prophet and also the names of 84 tãbi'ín (disciples of the companions) who have narrated the hadíth of Ghadir. He has also chronologically given the names of the historians, traditionalists, exegetists and poets who have mentioned the hadíth of Ghadir from the first till the fourteenth Islamic century.

The late Sayyid 'Abdu 'l-'Azíz at-Tabãtabã'í has stated that there probably is not a single hadíth that has been narrated by so many companions as the number we see (120) in the hadíth of Ghadír. However, comparing that number to the total number of people who were present in Ghadír Khumm, he states that 120 is just ten percent of the total audience. And so he rightly gave the following title to his paper: "Hadíth Ghadír: Ruwãtuhu Kathíruna lil-Ghãyah...Qalíluna lil-Ghãyah - Its Narrators are Very Many...Very Few".

4. Shaban & His New Interpretation

Among the latest work by Western scholarship on the history of Islam is M.A. Shaban's Islamic History AD 600-750 subtitled as "A New Interpretation" in which the author claims not only to use newly discovered material but also to re-examine and re-interpret material which has been known to us for many decades. Shaban, a lecturer of Arabic at SOAS of the University of London, is not prepared to even consider the event of Ghadir Khumm. He writes, "The famous Shí'ite tradition that he [the Prophet] desginated 'Ali as his successor at Ghadir Khumm should not be taken seriously."

Shaban gives two 'new' reasons for not taking the event of Ghadir seriously:

"Such an event is inherently improbable considering the Arabs' traditional reluctance to entrust young and untried men with great responsibility. Furthermore, at no point do our sources show the Madinan community behaving as if they had heard of this designation."

Let us critically examine each of these reasons given by Shaban.

1. The traditional reluctance of the Arabs to entrust young men with great responsibility.

First of all, had not the Prophet introduced many things to which the Arabs were traditionally reluctant? Did not the Meccans accept Islam itself very reluctantly? Was not the issue of marrying a divorced wife of one's adopted son a taboo among the Arabs? This 'traditional reluctance,' instead of being an argument against the designation of 'Ali, is actually part of the argument used by the Shí'as. They agree that the Arabs (in particular, the Quraysh) were reluctant to accept 'Ali as the Prophet's successor not only because of his young age but also because he had killed their leaders in the early battles of Islam. According to the Shí'as, Allãh also knew about this reluctance and that is why after ordering the Prophet to proclaim 'Ali as his successor ("O the Messenger! Convey what had been revealed to you..."), He reassured His Messenger by saying that, "Allãh will protect you from the people." (5:67) The Prophet was commissioned to convey the message of Allãh, no matter whether the Arabs liked it or not.

Moreover, this 'traditional reluctance' was not an irrevocable custom of the Arab society as Shaban wants us to believe. Jafri, in The Origin and Early Development of Shí'a Islam, says, "[O]ur sources do not fail to point out that, though the 'Senate' (Nadwa) of pre-Islamic Mecca was generally a council of elders only, the sons of the chieftain Qusayy were privileged to be exempted from this age restriction and were admitted to the council despite their youth. In later times more liberal concessions seems to have been in vogue; Abu Jahl was admitted despite his youth, and Hakim b. Hazm was admitted when he was only fifteen or twenty years old." Then Jafri quotes Ibn 'Abd Rabbih, "There are no monarchic king over the Arabs of Mecca in the Jahiliya. So whenever there was a war, they took a ballot among chieftains and elected one as 'King', were he a minor or a grown man. Thus on the day of Fijar, it was the turn of the Banu Hashim, and as a result of the ballot Al-'Abbãs, who was then a mere child, was elected, and they seated him on the shield."

Thirdly, we have an example in the Prophet's own decisions during the last days of his life when he entrusted the command of the army to Usãmah bin Zayd, a young man who was hardly twenty years of age.

He was appointed over the elder members of the Muhãjirín (the Quraysh) and the Ansãr; and, indeed, many of the elders resented this decision of the Prophet.

If the Prophet of Islam could appoint the young and untried Usãmah bin Zayd over the elders of the Quraysh and Ansãr, then why should it be "inherently improbable" to think that the Prophet had designated 'Ali as his successor?

2. The traditional reluctance to entrust untried men with great responsibility.

Apart from the young age of 'Ali, Shaban also refers to the reluctance of the Arabs in entrusting "untried men with great responsibility." This implies that the Arabs selected Abu Bakr because he had been "tried with great responsibilities." I doubt whether Mr. Shaban would be able to substantiate the implication of his claim from Islamic history. One will find more instances where 'Ali was entrusted by the Prophet with greater responsibilities than was Abu Bakr. 'Ali was left behind in Mecca during the Prophet's migration to mislead the enemies and also to return the properties of various people which were given in trust to the Prophet. 'Ali was tried with greater responsibilities during the early battles of Islam in which he was always successful. When the ultimatum (barã'at) against the pagan Arabs of Mecca was revealed, first Abu Bakr was assigned to convey it to the Meccans; but later on this great responsibility was taken away from him and entrusted to 'Ali. 'Ali was entrusted with safety of the city and citizens of Medina while the Prophet had gone on the expedition to Tabûk. 'Ali was appointed the leader of the expedition to Yemen. These are just the few examples that come to mind at random. Therefore, on a comparative level, 'Ali bin Abu Tãlib was a person who had been tried and entrusted with greater responsibilities more than Abu Bakr.

3. The behaviour of the Madinan community about declaration of Ghadir Khumm.

Firstly, if an event can be proved true by the accepted standard of hadíth criticism (of the Sunnis, of course), then the reaction of the people to the credibility of that event is immaterial.

Secondly, the same 'traditional reluctance' used by Shaban to discredit the declaration of Ghadir can be used here against his scepticism towards the event of Ghadir. This traditional reluctance, besides other factors that are beyond the scope of this paper,

can be used to explain the behaviour of the Madinan community.

Thirdly, although the Madinan community was silent during the events which kept 'Ali away from caliphate, there were many among them who had witnessed the declaration of Ghadir Khumm. On quite a few occasions, Imam 'Ali implored the companions of the Prophet to bear witness to the declaration of Ghadir. Here I will just mention one instance that took place in Kufa during the reign of Imam 'Ali, about 25 years after the Prophet's death.

Imam 'Ali heard that some people were doubting his claim of precedence over the previous caliphs, therefore, he came to a gathering at the mosque and implored the eyewitnesses of the event of Ghadir Khumm to verify the truth of the Prophet's declaration about his being the lord and master of all the believers. Many companions of the Prophet stood up and verified the claim of 'Ali. We have the names of twenty-four of those who testified on behalf of 'Ali, although other sources like Musnad of Hanbal and Majma' az-Zawã'id of Hãfidh al-Haythami put that number at thirty. Also bear in mind that this incident took place 25 years after the event of Ghadir Khumm, and during this period hundreds of eye witnesses had died naturally or in the battles fought during the first two caliphs' rule. Add to this the fact that this incident took place in Kufa which was far from the centre of the companions, Medina. This incident that took place in Kufa in the year 35 AH has itself been narrated by four companions and fourteen tãbi'in and has been recorded in most books of history and tradition.

In conclusion, the behaviour of the Madinan community after the death of the Prophet does not automatically make the declaration of Ghadir Khumm improbable. I think this will suffice to make Mr. Shaban realize that his is not a 'new' interpretation; rather it exemplifies, in my view, the first stage of the classical response of the Sunni polemicists-an outright denial of the existence of an event or a hadíth which supports the Shí'a view-which has been absorbed by the majority of Western scholars of Islam.

5. The Meaning of "Mawla"

The last argument in the strategy of the Sunni polemicists in their response to an event or a hadíth presented by the Shí'as is to give it an interpretation that would safeguard their beliefs. They exploit the fact that the word "mawla" has various meanings: master, lord, slave, benefactor, beneficiery, protector, patron, client, friend, charge, neighbour, guest, partner, son, uncle, cousin, nephew, son-in-law, leader, follower. The Sunnis say that the word "mawla" uttered by the Prophet in Ghadir does not mean "master or lord", it means "friend".

On the issue of the hadíth of Ghadír, this is the stage where the Western scholarship of Islam has arrived. While explaining the context of the statement uttered by the Prophet in Ghadir Khumm, L. Veccia Vaglieri follows the Sunni interpretation. She writes:

On this point, Ibn Kathír shows himself yet again to be percipient historian: he connects the affair of Ghadir Khumm with episodes which took place during the expedition to the Yemen, which was led by 'Ali in 10/631-2, and which had returned to Mecca just in time to meet the Prophet there during his Farewell Pilgrimage. 'Ali had been very strict in the sharing out of the booty and his behaviour had aroused protests; doubt was cast on his rectitude, he was reproached with avarice and accused of misuse of authority. Thus it is quite possible that, in order to put an end to all these accusations, Muhammad wished to demonstrate publicly his esteem and love for 'Ali. Ibn Kathir must have arrived at the same conclusion, for he does not forget to add that the Prophet's words put an end to the murmuring against Ali.

Whenever a word has more than one meaning, it is indeed a common practice to look at the context of the statement and the event to understand the intent of the speaker. Ibn Kathir and other Sunni writers have connected the event of Ghadir Khumm to the incident of the expedition to Yemen. But why go so far back to understand the meaning of "mawla", why not look at the whole sermon that the Prophet gave at Ghadir Khumm itself? Isn't it a common practice to look at the immediate context of the statement, rather than look at remote events, in time and space?

When we look at the immediate context of the statement uttered by the Holy Prophet in Ghadir Khumm, we find the following:

1. The question that the Prophet asked just before the declaration. He asked, "Do I not have more authority upon you (awla bi kum) than you have yourselves?" When the people replied, "Yes, surely," then the Prophet declared: "Whosoever's mawla am I, this 'Ali is his mawla." Surely the word "mawla", in this context, has the same meaning as the word "awla: have more authority".

2. After the declaration, the Prophet uttered the following prayer: "O Allãh! Love him who loves 'Ali, and be enemy of the enemy of 'Ali; help him who helps 'Ali, and forsake him who forsakes 'Ali." This prayer itself shows that 'Ali, on that day, was being entrusted with a position that would make some people his enemies and that he would need supporters in carrying out his responsibilities. This could not be anything but the position of the mawla in the sense of ruler, master and lord. Are helpers ever needed to carry on a 'friendship'?

3. The statement of the Prophet in Ghadir that: "It seems imminent that I will be called away (by Allãh) and I will answer the call." It was clear that the Prophet was making arrangements for the leadership of the Muslims after his death.

4. The companions of the Prophet congratulated 'Ali by addressing him as "Amirul Mumineen - Leader of the Believers". This leaves no room for doubt concerning the meaning of mawla.

5. The occasion, place and time. Imagine the Prophet breaking his journey in mid-day and detaining nearly one hundred thousand travellers under the burning sun of the Arabian desert, making them sit in a thorny place on the burning sand, and making a pulpit of camel saddles, and then imagine him delivering a long sermon and at the end of all those preparations, he comes out with an announcement that "Whosoever considers me a friend, 'Ali is also his friend!" Why? Because some (not all the hundred thousand people who had gathered there) were upset with 'Ali in the way he handled the distribution of the booty among his companions on the expedition to Yemen! Isn't that a ridiculous thought?

Another way of finding the meaning in which the Prophet used the word "mawla" for 'Ali is to see how the people in Ghadir Khumm understood it. Did they take the word "mawla" in the sense of "friend" or in the meaning of "master, leader"?

Hassãn ibn Thãbit, the famous poet of the Prophet, composed a poem on the event of Ghadir Khumm on the same day. He says:

He then said to him: "Stand up, O 'Ali, for

I am pleased to make you Imam & Guide after me.

In this line, Hassãn ibn Thãbit has understood the term "mawla" in the meaning of "Imam and Guide" which clearly proves that the Prophet was talking about his successor, and that he was not introducing 'Ali as a "friend" but as a "leader".

Even the words of 'Umar ibn al-Khattãb are interesting. He congratulated Imam 'Ali in these words: "Congratulations, O son of Abu Tãlib, this morning you became mawla of every believing man and woman."

If "mawla" meant "friend" then why the congratulations? Was 'Ali an 'enemy' of all believing men and women before the day of Ghadir?

These immediate contexts make it very clear that the Prophet was talking about a comprehensive authority that 'Ali has over the Muslims comparable to his own authority over them. They prove that the meaning of the term "mawla" in hadíth of Ghadír is not "friend" but "master, patron, lord, or leader".

Finally, even if we accept that the Prophet uttered the words "Whomsoever's mawla I am, this 'Ali is his mawla" in relation to the incident of the expedition to Yemen, even then "mawla" would not mean "friend". The reports of the expedition, in Sunni sources, say that 'Ali had reserved for himself the best part of the booty that had come under the Muslims' control. This caused some resentment among those who were under his command. On meeting the Prophet, one of them complained that since the booty was the property of the Muslims, 'Ali had no right to keep that item for himself. The Prophet was silent; then the second person came with the same complaint. The Prophet did not respond again. Then the third person came with the same complaint. That is when the Prophet became angry and said, "What do you want with 'Ali? He indeed is the waliy after me."

What does this statement prove? It says that just as the Prophet, according to verse 33:6, had more right (awla) over the lives and properties of the believers, similarly, 'Ali as the waliy, had more right over the lives and properties of the believers. The Prophet clearly puts 'Ali on the highest levels of authority (wilãyat) after the Prophet himself. That is why the author of al-Jãmi'u 's-Saghír comments, "This is indeed the highest praise for 'Ali."

6. Conclusion

In this brief survey, I have shown that the event of Ghadir Khumm is a historical fact that cannot be rejected; that in studying Shí'ism, the precommitment to Judeo-Christian tradition of the Orientalists was compounded with the Sunni bias against Shí'ism. Consequently, the event of Ghadir Khumm was ignored by most Western scholars and emerged from oblivion only to be handled with scepticism and re-interpretation.

I hope this one example will convince at least some Western scholars to re-examine their methodology in studying Shí'ism; instead of approaching it largely through the works of heresiographers like ash-Shahristãni, Ibn Hazm, al-Maqrizi and al-Baghdãdi who present the Shí'as as a heretical sect of Islam, they should turn to more objective works of both the Shí'as as well as the Sunnis.

The Shí'as are tired, and rightfully so, of being portrayed as a heretical sect that emerged because of political circumstances of the early Islamic period. They demand to represent themselves instead of being represented by their adversaries.

* * *

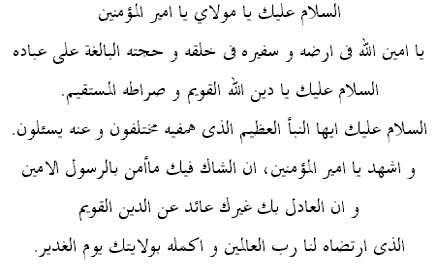

Peace be upon you,

O my Master, Amiru 'l-Mu'minin!

O the trustee of Allãh in His earth,

His representative among His creatures,

and His convincing proof for His servants...

Peace be upon you,

O the upright religion of Allãh and His straight path.

Peace be upon you, O the great news about whom they disputed and about whom they will be questioned.

I bear witness, O Amiru 'l-Mu'minin,

that the person who doubts about you

has not believed in the trustworthy Messenger;

and one who equates you to others has astrayed

from the upright religion which

the Lord of the universe has chosen for us and

which He has perfected through your wilãyat

on the day of Ghadir.

(Excerpts from Ziyãrat of the Day of Ghadír)

33%

33%

Author: Sayyid Muhammad Rizivi

Author: Sayyid Muhammad Rizivi