III- HISTORY OF THE TEXT

Muhammad b. `Alî Raqqâm informs us, in his preface to theHadîqa

, that while Sanâ'î was yet engaged in its composition, some portions were abstracted and divulged by certain ill-disposed persons. Further, `Abdu'l-Latîf in his preface, theMirâtu'l-Hadâ'iq

, states that the disciples of Sanâ'î made many different arrangements of the text, each one arranging the matter for himself and making his own copy; and that thus there came into existence many and various arrangements, and two copies agreeing together could not be found.

The confusion into which the text thus fell is illustrated to some extent by the MSS. which I have examined for the purpose of this edition. C shows many omissions as compared with later MSS.; at the same time there is a lengthy passage, 38 verses, which is not found in any other; H, though also defective, is fuller than C but evidently belongs to the same family. M contains almost all the matter comprised in `Abdu'l-Latîf's recension, much of it twice over as has already been mentioned; and in addition about 300 verses, or altogether 10 folia, which apparently do not of right belong to this first chapter at all; the first chapter, too, is here divided into two chapters. The remaining MSS. and lithographs agree closely with each other and are evidently all nearly related.

The same story, of an early confusion of the text, is even more strikingly brought out if, instead of the omissions and varying extent of the text in the several MSS., we compare the order of the text. Here M startles us by giving us an order totally at variance with that of any other of our sources. There seems to be no reason for this: the arrangement of the subject is not, certainly, more logical; and it would appear that the confusion has simply been due to carelessness at some early stage of the history of the text; the repetitions, and the inclusions of later parts of the work, point to the same explanation. I need only mention the consequent labour and expenditure of time on the collation of this manuscript. C and H agree mostly between themselves in the order of the text, and broadly speaking the general order is the same as that of the later MSS.; the divergences would no doubt have appeared considerable, but that they are entirely overshadowed by the confusion exhibited by M. IALB agree closely with each other, as before.

The same confusion is again seen in the titles of the various sections as given in the several MSS. I am inclined to doubt how far any of the titles are to be considered as original; and it seems to me very possible that all are later additions, and that the original poem was written as one continuous whole, not divided up into short sections as we have it now. At any rate, the titles vary very much in the different MSS.; some, I should say, were obviously marginal glosses transferred to serve as headings; in other cases the title has reference only to the first few lines of the section, and is quite inapplicable to the subject-matter of the bulk of the section; in other cases again it is difficult to see any applicability whatever. It appears to have been the habit of the copyists to leave spaces for the titles, which were filled in later; in some cases this has never been done in others, through some omission in the series, each one of a number of sections will be denoted by a title which corresponds to that of the text following section in other MSS.

It is then obvious that `Abdu'l-Latîf is right in saying that in the centuries following Sanâ'î's death great confusion existed in the text of theHadîqa

. This text he claims to have purified and restored, as well as explained by means of his commentary; and it is his recension which is given in A, as well as in the Indian lithographs Land B. He says that he heard that the Nawâb Mirzâ Muhammad `Azîz Kaukiltâsh, styled the Great Khân, had, while governor of Gujrât in the year 1000 A.H., sent to the town of Ghaznîn a large sum of money in order to obtain from the tomb of Sanâ'î a correct copy of theHadîqa

, written in an ancient hand; this copy the Nawâb, on his departure on the pilgrimage, had bestowed on the Amîr `Abdu'r-Razzâq Ma`mûri, styled Muz

affar Khan, at that time viceroy of that country. `Abdu'l-Latîf, however, being then occupied in journeys in various parts of India, could not for some time present himself before the Amîr; till in A.H. 1035 this chief came to Agra, where `Abdu'l-Latîf presented himself before him and obtained the desire of so many years. This MS. of theHadîqa

had been written only 80 years after the original composition, but the text did not satisfy the editor, and it was besides deficient, both in verses here and there, and also as regards twenty leaves in the middle of the work.

In the year A.H. 1037 `Abdu'l-Latîf came to Lahore, where having some freedom from the counterfeit affairs of the world and the deceitful cares of this life, he entered again on the task of editing the text, with the help of numerous copies supplied to him by learned and critical friends; He adopted the order of the ancient MS. before-mentioned, and added thereto such other verses as he found in the later MSS. which appeared to be of common origin, and to harmonize in style and dignity and doctrine, with the text. As to what `Abdu'l-Latîf attempted in his commentary, v. p. xxiipost

.

So far `Abdu'l-Latîf's own account of his work. We can, however, supplement this by a number of conclusions derived from the MSS. themselves.

In the first place, it appears that A is not, as stated in the India Office Catalogue, `Abdu'l-Latîf's autograph copy. The statement that it is so is apparently based on the fact of the occurrence of the words "harrarahu wa sawwadahu `Abdu'l-Latîf. b. 'Abdu'llâhi'l-`Abbâsî

," at the end of the editor's few words of introduction to Sanâ'î's preface and again of the occurrence of the words "harrarahu `Abdu'l-Latîf . ki shârih wa niusahhih-i în kitâb-i maimunat ni

sâb ast

," at the end of the few lines of introduction immediately preceding the text. But both these sentences are found in the Lucknow lithograph, and therefore must have been copied in all the intermediate MSS. from `Abdu'l-Latîf's autograph downwards the words in each case refer only to the paragraph to which they are appended, and were added solely to distinguish these from Sanâ'î's own writings.

1 cannot find any other facts in favour of the statement that A is the editor's autograph; there are, however, many against it. Thus A is beautifully written, and is evidently the work of a skilled professional scribe, not of a man of affairs and a traveller, which `Abdu'l-Latîf represents himself as having been. Again, there are occasional explanatory glosses to the commentary, in the original hand; these would have been unnecessary had the scribe been himself the author of the commentary. The handwriting is quite modern in character and the pointing is according to modern standards throughout; the late date of A is immediately brought out clearly by comparing it with I (of date 1027 A.H.) or M (of date 1076 A.H.); though the supposed date of A is 1044 A.H. it is obviously much later than either of the others. But perhaps the most curious bit of evidence is the following; at the top of fol. 11b

of the text of A there is an erasure, in which is written ### in place of an original reading ###, and as it happens this line is one which has been commented on by the editor; in the margin is a note in a recent hand,--###, which is true,--the commentary certainly presumes a reading ###, but this MS. had originally ###; the scribe could not therefore have been the commentator himself, i.e., `Abdu'l-Latîf

Further, not only is A not `Abdu'l-Latîf's autograph, but it does not accurately reproduce that autograph. I refer to 34 short passages of Sanâ'î's text, which in A are found as additions in the margin; these, though obviously written in the same hand, I regard as subsequent additions from another source by the same scribe, not as careless omissions filled in afterwards on comparing the copy with the original. In the first place, the scribe was on the whole a careful writer; and the mistakes he has made in transcribing the commentary, apart from the text, are few. The omissions of words or passages of commentary, which have been filled in afterwards, are altogether 10; of these, two are of single words only; two are on the first page, when perhaps the copyist had not thoroughly settled down to his work; five are short passages, no doubt due to carelessness; and one is a longer passage, the whole of a comment on a certain verse,--an example of carelessness certainly, but explicable by supposing that the scribe had overlooked the reference number in the text indicating that the comment was to be introduced in relation to that particular verse. Roughly speaking, the commentary is of about equal bulk with the text; yet the omissions of portions of commentary by the copyist are thus many fewer in number and much less in their united extent than the omissions of the text,--supposing, that is, that the marginal additions to the text in A are merely the consequence of careless copying. The reverse would be expected, since owing to the manner of writing, it is easier to catch up the place where one has got to in a verse composition; it would seem therefore. as said above, that the comparatively numerous marginal additions to the text are rather additions introduced afterwards from another source than merely careless omissions in copying. In the second place, none of these 34 passages are annotated by `Abdu'l-Latîf; in all likelihood, if they had formed part of his text, some one or more of the lines would have received a comment. The passages comprise, together, 63 verses; there is only one instance in the First chapter of theHadîqa

of a longer consecutive passage without annotation, and in general it is rare (eleven instances only) to find more than 30 consecutive verses without annotation; usually the editor's comments occur to the number of two, three or more on each page of 15 lines. I think, therefore. it must be admitted that the chances would be much against a number of casual omissions aggregating 63 lines falling out so as not to include a single comment of the editor. Thirdly, it is a remarkable fact that of these 34 passages the great majority are also omitted in both C and H, while they are present in both M and 1; to particularize, C omits 30 ½, H omits 28, both C and H omit 25 ½, and either C or H or both omit every one of these 34 passages; while I and M each have all the 34 with one exception in each case; further, while many of these 34 marginally added passages in A correspond exactly to omissions in H, the corresponding omissions in C may be more extensive, i.e., may include more, in each case, of the neighbouring text.

We must therefore, I think, conclude that after completing the transcription of A the scribe obtained a copy of theHadîqa

of the type of I or M, and filled in certain additions therefrom; and that '`Abdu'l-Latîf's edition did not originally contain these passages.

Let us turn to a consideration of I and its relation to `Abdu'l-Latîf's edition. I is dated A.H. 1027; it is, therefore, earlier than `Abdu'l-Latîf's edition of A.H. 1044. As we have seen, A is not `Abdu'l-Latîf's autograph; but we have, I think, no reason to doubt that it was either copied from that autograph, or at any rate stands in the direct line of descent; so much seems to be attested by the occurrence of the words --"harrarahu `Abdu'l-Latîf

. . . " and by the inscription at the end as to the completion of the book in A.H. 1044, the actual date of the completion of `Abdu'l-Latîf's work. Regarding, then, A as presenting us (with the exception of the marginally added passages) with a practically faithful copy of `Abdu'l-Latîf's own text, we notice a striking correspondence between this text and that of I. As to the general agreement of the readings of the two texts, a glance at the list of variants will be sufficient; and it is not impossible to find whole pages without a single difference of any importance. The titles also, which as a rule vary even so much in the different MSS., correspond closely throughout. The order of the sections is the same throughout; and the order of the lines within each section, which, ' is also very variable in the various M88., corresponds in I and A with startling closeness. The actual spellings of individual words also, which vary even in the same MS., are frequently the same in I and A; for example, at the bottom of p. ### of the present text the word ### or ### occurs three times within a few lines. The word may also be written ###, ###; thus while C and M have ###, H has first ### and then twice ###; I however has first ### and then twice ###; and this is exactly repeated in A. Another example occurs a few lines afterwards (p. ###, l. ###); the reading is ###,mâr-i shikanj

,mâr

being followed by the izâdfat; this I writes as ###; in A an erasure occurs between ### and ###, doubtless due to the removal of a ### originally written there as in I.

The above will serve to show the close relation between I and A, or between I and `Abdu'l-Latîf's autograph, of which A is a copy or descendant. But, however close this relationship, `Abdu'l-Latîf cannot actually have used I in the preparation of his revision of the text, or he would certainly have incorporated many of the 34 passages before alluded to, which were all, with one exception, contained in 1. These, we have seen, were only added by the scribe of A, and by him only subsequently, from another source, after he had completed his transcription from `Abdu'l-Latîf's autograph.

The facts, then, are these. There was in existence, before `Abdu'l-Latîf's time, a tradition, probably Persian, of the order of the text, which he adopted even in detail. This is represented for us by I, written A.H. 1027 at Is

fahân; but I itself is somewhat fuller than the copy of which `Abdu'l-Latîf if made such great use. This copy may be called P. Such use, indeed, did `Abdu'l-Latîf make of P, that, so far as can be seen, it is only necessary that he should have had P before him, with one or two other copies from which he derived a certain number of variant readings, which he substituted here and there in his own edition for those of P.

We have now brought down the history of the text to A.H. 1044. Not much remains to be said; A, as we have seen, is quite possibly a direct copy of `Abdu'l-Latîf's autograph, with, however, marginal additions from another source. This other source might be at once assumed to be 1, but for the fact that only 33 out of the 34 marginally added passages occur in I; and it still seems to me at least possible that I was thus used. 1, though written at Is

fahân, was probably by this time in India, where A, the so-called "Tippu MS.," was certainly written; at least, that I did come to India may be assumed from its presence in the India Office Library. Again, though it is, I think, impossible that the whole of the 34 passages added marginally in A should have been careless omissions of the copyist, one or two might possibly be so, and it is possible that the single line now under discussion may be such an omission, filled in from the scribe's original, not from another source. Finally it is, of course, always possible that the additions were taken from two sources, not one only; i.e., that while perhaps even 33 were filled in after comparison with I, the single remaining line may have been derived from elsewhere. Though absent in C, it is present in both H and M.

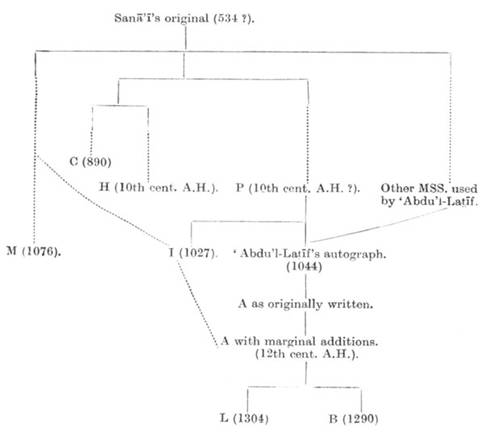

As to the lithographs, both are obviously descendants of A. The above conclusions may be summarized in the followingstemma codicum

.

28%

28%

Author: Sanai of Ghazna

Author: Sanai of Ghazna